History

April 2, 2024

Who Remembers Floppy Disks?

The Rise and Fall of 3M’s Floppy Disk

The high-profile creator of magnetic media gave it up nearly three decades ago

8 hours ago

10 min read

3M’s floppies were not unique, but they were emblematic of an early computing era.

IEEE Spectrum

3m floppycomputer historyaudio tapemasking tape

A version of this post originally appeared onTedium, Ernie Smith’s newsletter, which hunts for the end of the long tail.

If you ask the average person what the company 3M does, odds are if they have a few gray hairs hanging out on their scalp, they might say that the company makes floppy disks. Now, this was once true, but if you look on 3M’s own website, you will see no mention of this legacy—it’s a firm that sells abrasive materials, adhesive tapes, filters, films, personal protective equipment, and medical equipment. (Younger people, if they recognize 3M, it’s probably because of Post-it notes, or more recently its N95 masks)

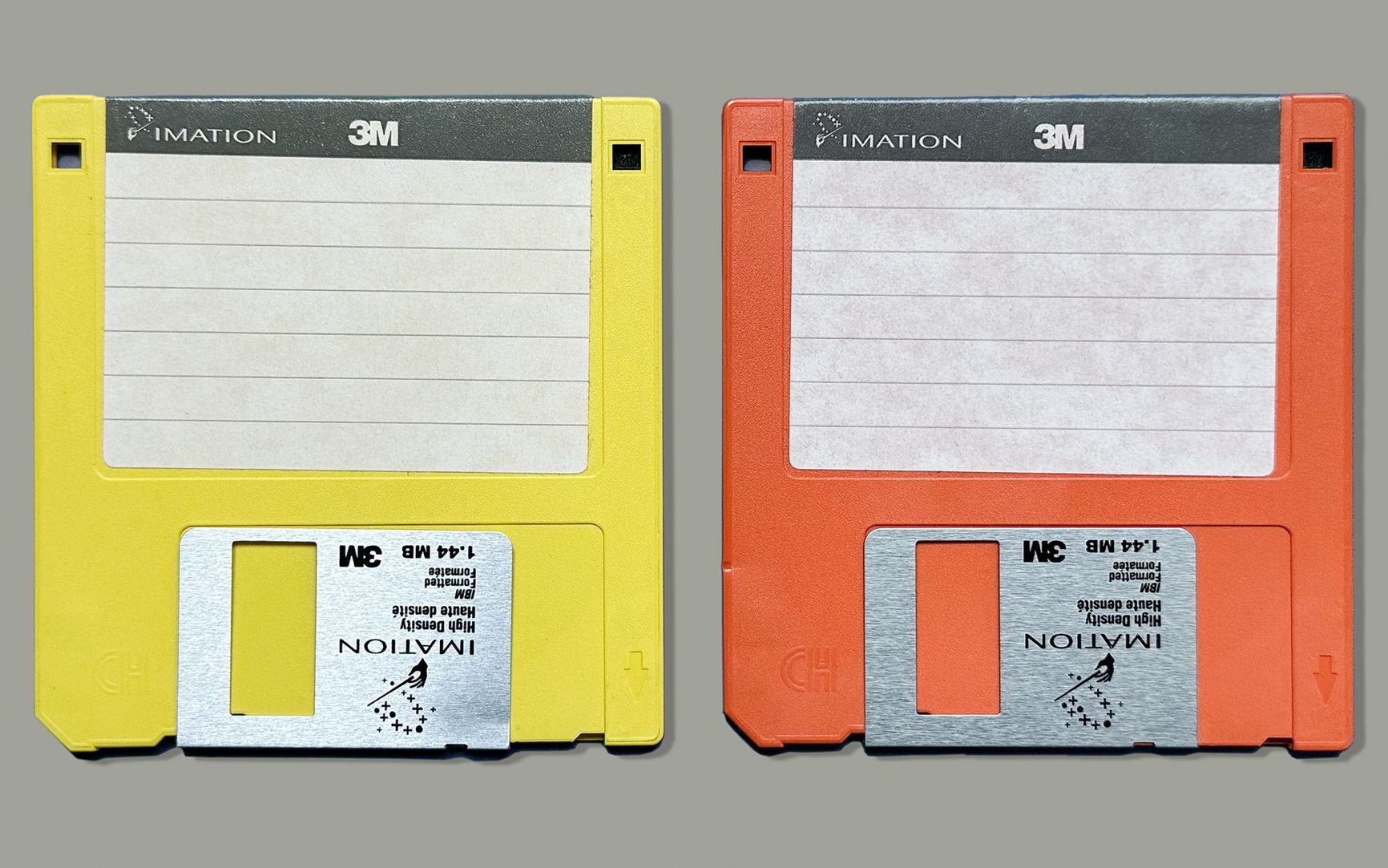

Floppies have had a surprisingly long life—in January 2024, Japan announced it will no longer require floppy-disk copies of government submissions. But 3M got out of the data-storage business about 28 years ago, when it transferred its floppy disk manufacturing to a spin-off called Imation. Imation is still around, under the name Glassbridge Enterprises, but with a much smaller profile.

3M’s spin-off, Imation, continued producing floppy disks after 3M itself left the business. IEEE Spectrum

Even with that said, those gray-hairs will frequently claim that of the many makers of floppies out there, 3M made the best ones. Given that, I was curious to figure out exactly why 3M became the most memorable brand in data storage during the formative days of computing, and why it abandoned the product.

How 3M Became a Key Innovator in the Production of Magnetic Data Storage

Now, to be clear, 3M did not invent magnetic storage—that was done by Austro-German engineer Fritz Pfleumer, in 1928. He created audio tape, a recording medium that started as broad strips of paper coated with iron-powder granules, and eventually moved to less-fragile cellulose acetate with help from what would become another big name in floppy disks, BASF. At first, the innovation didn’t spread outside of Germany because of World War II.

Nor was 3M the first company to popularize magnetic media— that was Ampex, which commercialized the tape recorder in the late 1940s. That was the point when magnetic tape turned into a major innovation in the world of music—one that, famously, Bing Crosby got to first because he gave financial support to Ampex. Incidentally, Ampex’s later spinoff, Memorex, represented Silicon Valley’s first true startup.

“Of all the businesses 3M has shed over its 100 years, the two seminal decisions that people point to as most significant involved the sale of 3M’s Duplicating Products business to Harris Corporation in Atlanta, Georgia, and the spin-off of 3M’s data-storage and imaging-systems businesses in 1996 creating a new company called Imation in Oakdale, Minnesota…”

Before World War II, one company did attempt to manufacture a tape recorder in the U.S. based on Pfluemer’s magnetic-tape invention. That firm, the Brush Development Co., had developed a device called the Soundmirror, produced by a Hungarian inventor named Semi J. Begun, who was likely something of a competitor to Pfleumer: Also a German, he had moved to the United States and developed a steel-based magnetic tape. The invention was used by the U.S. military during the war, and the company revisited the idea immediately after. But, it needed someone to manufacture magnetic tape for it to use.

As author David Morton noted in his 2006 book Sound Recording: The Life Story of a Technology, 3M was one of the best-suited companies on the market to help Brush out. That’s because the groundbreaking work that the company had done to develop pressure-sensitive adhesive tape was an essential element of making magnetic tape effective.

3M’s adhesive-tape technology transferred readily to magnetic tape. 3M

Strangely enough, Richard Gurley Drew, the inventor of much of 3M’s tape technology, was a musician—he played banjo in a local orchestra—when he took a job with the company. He probably didn’t realize he was inventing a key element of 20th-century recording technology when he observed that auto body shops needed a way to “mask off” areas of vehicles that were being whittled down with sandpaper, but his observation would prove useful to the invention of masking tape.

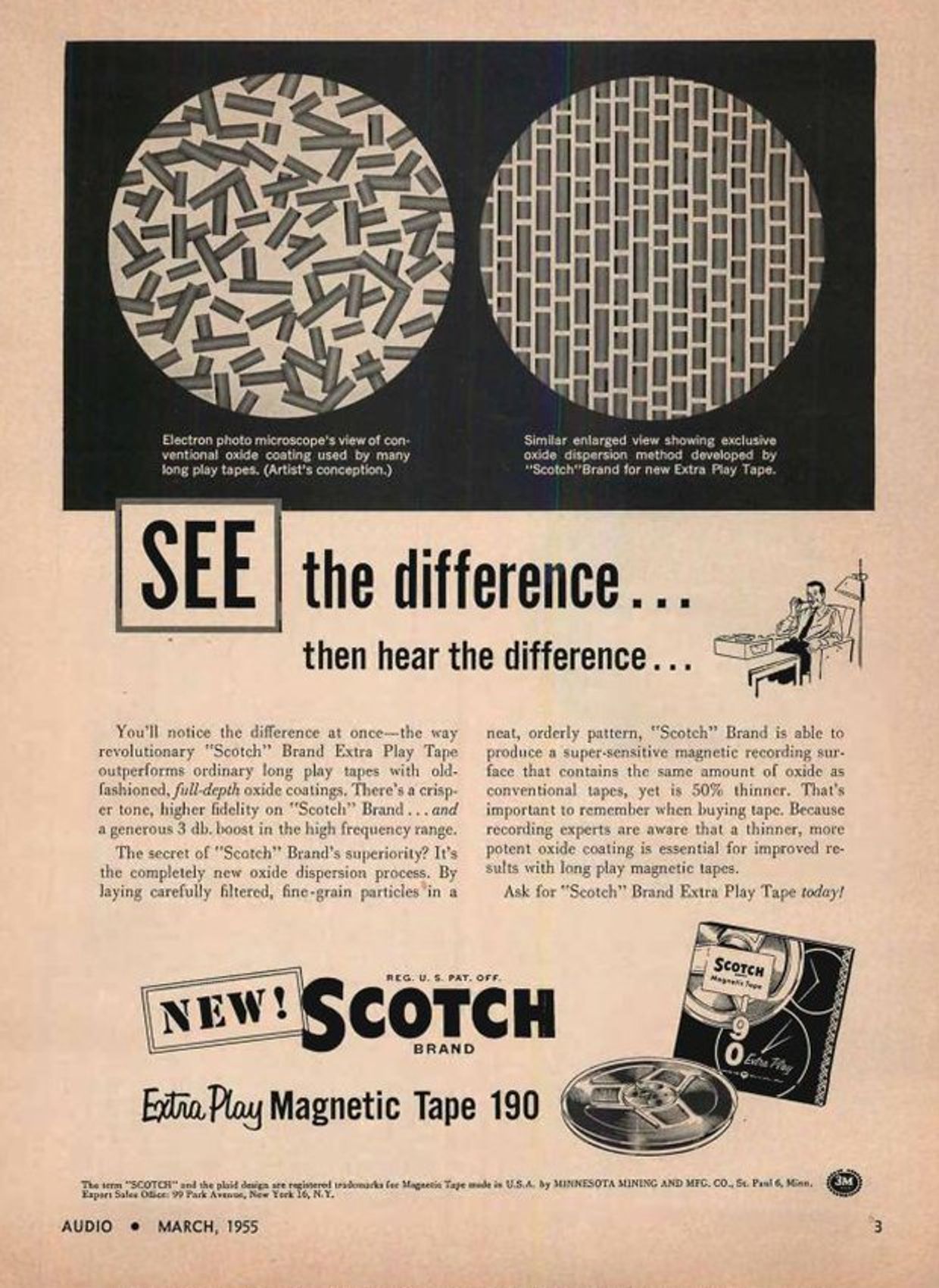

In the mid-1950s, 3M advertised its Scotch audio reel-to-reel tape.Audio Magazine/Internet Archive/Scotch

In the mid-1950s, 3M advertised its Scotch audio reel-to-reel tape.Audio Magazine/Internet Archive/Scotch

As Smithsonian Magazine notes, the formulation he developed, combining cabinetmaker’s glue with glycerin, proved to be just the right level of easy-to-remove adhesive that it became an out-and-out phenomenon. You might know his invention, developed in 1925, as Scotch Tape.

In 1930, he followed it up with another invention that was even more amazing—tape made from cellophane, which by its nature was totally transparent. Another 3M employee developed the tape dispenser, and the two inventions reshaped offices the world over.

So, when Brush looked to others to produce its recording medium, 3M was well positioned to help out due to magnetic tape’s similarity with its Scotch Tape. Brush eventually moved to other manufacturers, like Dupont. But the experience led 3M to continue developing metal-oxide tape technology, leading to the creation of the Scotch 111 reel-to-reel tape, which was one of the most popular types used in recording studios throughout the 1950s, according to the Museum of Magnetic Sound Recording.

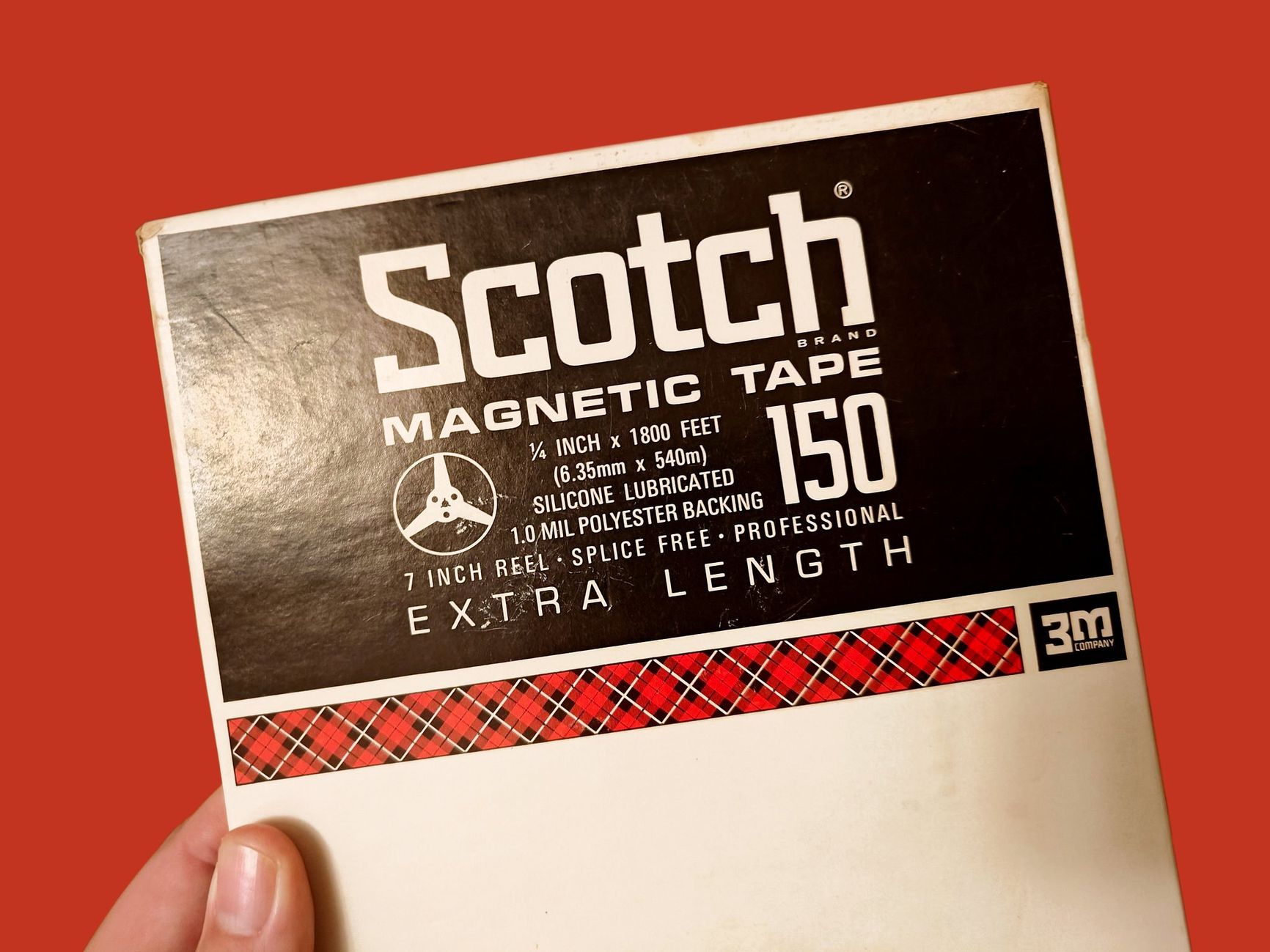

I admittedly have long had a fascination with these reel-to-reel tapes. A number of years ago, back when I lived in Milwaukee, I found a couple of blank reel-to-reel tapes created by 3M using the Scotch name. I bought them from a junk store, and maybe paid $2 for them. They managed to follow me through three states and five cities, and now sit on my intentionally organized pile of junk. Based on my analysis of the container and the logotype it uses, they date to the mid-1960s or earlier. (No, I have not tried to record on them.)

I’ve owned this blank Scotch 150 reel-to-reel tape for nearly 20 years. It is 50 to 60 years old. Ernie Smith

For years, 3M’s reel-to-reels had one of the strongest reputations in the music industry; they were built to be of superhigh quality. But you might be wondering, how did 3M make the leap from reel-to-reel tape to floppies? It feels like just as strange a leap as a masking tape company developing reel-to-reel audio tape.

But, again, it happened.

How 3M’s Tapes Went From Music to Data

3M didn’t develop the floppy disk drive, either. IBM did, and Shugart Associates further improved it by making it small enough for regular users.

3M manufactured a signature 5.25-inch floppy disk. IEEE Spectrum

But 3M, much as with mechanical tape, was well positioned to improve on it, leveraging its skills with mechanical media in the budding computing industry. In a way, 3M came to media manufacturing from the opposite direction than its disk-selling competitor Memorex did. Memorex started with computers and gradually came to develop and improve tape-based technology, which eventually evolved into floppy disks. On the other hand, 3M started with the raw materials and the manufacturing processes, and combined those into computing’s greatest commodity item, the floppy disk.

3M got into the floppy disk market around the fall of 1973. It was not the only manufacturer of disks out there—some names from this era include Verbatim, Control Data, Dysan, and BASF. Most of these companies started with computing technology—for example, Dysan worked closely with Shugart Associates on the 5.25-inch floppy. But 3M wasn’t alone in starting with the raw materials. BASF, a German chemical manufacturer, has a somewhat similar corporate history and logo design to fellow thick-Helvetica enthusiast 3M. (Though 3M obviously never associated with the Nazis during World War II, so there’s that.)

3M branched out beyond standard floppy disks with a variety of magnetic-tape storage media.ComputerWorld/Google Books/3M

3M branched out beyond standard floppy disks with a variety of magnetic-tape storage media.ComputerWorld/Google Books/3M

3M didn’t rest on its laurels with the floppy disk either, and tried to push the technology further, most notably with Floptical disk technology, which Jim Adkisson, who helped create the 5.25-inch floppy at Shugart Associates, developed in the 1980s. A partnership of 3M, Maxell, and Iomega created the Floptical disk, which could hold 20 megabytes of data on something that looked a lot like a 3.5-inch floppy. Unfortunately the floptical disk flopped, losing out to products like Iomega’s iconic Zip drives.

3M also worked in more specialized media, developing high-capacity optical disks that fit into standard floppy and optical disk mechanisms, as well as high-end tape drives intended for the server room rather than your cassette player.

In many ways, 3M was out front on one of the most important elements of computing and was making huge profits from it. But by the end of 1995, those days were done. What changed?

https://www.youtube.com/embed/bOHKgENMcGQ?rel=03M advertised its floppy disk as more reliable than the competition in no uncertain terms.

What Led 3M to Kick a Multibillion-Dollar Business to the Curb

By 1995, 3M’s magnetic-media arm had evolved into a US $2.3 billion business, according to Time, which made it a significant chunk of 3M’s overall offering.

But at that time, high technology— especially consumer technology—was starting to look like a bad bet for legacy companies. This was around the same period that AT&T, still smarting from misadventures like the EO Personal Communicator, spun off Bell Labs as Lucent Technologies.

3M’s story, in its own words, suggests a similar crisis of culture. In A Century of Innovation, a book published by the company in 2002, around the time of its 100-year anniversary, the company compared the creation of the spin-off, which it called “the most wrenching decision in its history,” to that of its determination eight years earlier to sell its Duplicating Products Division, which sold copying machines:

Of all the businesses 3M has shed over its 100 years, the two seminal decisions that people point to as most significant involved the sale of 3M’s Duplicating Products business to Harris Corporation in Atlanta, Georgia, and the spin-off of 3M’s data-storage and imaging-systems businesses in 1996 creating a new company called Imation in Oakdale, Minnesota, near 3M headquarters. The two decisions have several elements in common—both involved businesses that 3M created and, in fact, ranked number one in the marketplace for decades. They were “homegrown” businesses—largely created within 3M and commercialized and built with the energy of many internal sponsors and champions. The businesses were risky because the products were based on pioneering technologies. They not only changed the basis of competition; they also created all new, global industries. The businesses were highly profitable for decades, and they represented a significant share of the company’s total annual revenues. They also produced many of 3M’s next generation of leaders.

So what happened? Essentially, despite the company’s success working in industrial and professional settings, doing things for consumers like producing videotapes, floppy disks, and cassettes meant moving out of its comfort zone. These products, initially developed for businesses, grew so popular that they suddenly needed to be available at every big-box store and drugstore alike, and, Post-its aside, retail was not a fit for the kind of company 3M was.

But more significantly, other companies were simply better at undercutting, and per the corporate biography, that required some tough decisions to be made:

While it sold its products for little or no profit, its competition sold their products for even less. Even though the consumer business had huge growth potential, 3M had little experience with a low-cost, low-profit-margin model.

The markings were clear—exit this business, even though 3M invented it. To stay in the “dog fight” meant 3M had to invest enormous amounts of money in order to remain the low-cost producer, with no assurance that profit margins ever would improve. “Exiting it was the right decision,” [former senior vice president Al] Huber said.

Seeing what came after, it’s hard to disagree. While floppies were still a significant medium in the mid-1990s, it was obvious that they would not be enough capacity for the next generation of data hoarders. It would only be a couple of years before Apple would put the first dagger in the heart of the floppy disk with the iMac, breaking with tradition by releasing a personal computer in 1998 with no built-in floppy disk drive.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/3qkQi3zZVhg?rel=0Imation carried on a floppy-disk ad campaign through the late 1990s.

That was a harbinger of what was to come. Within a decade of the decision, floppy drives, compact cassettes, and videotapes—the three key elements of 3M’s move into consumer-driven magnetic media—had fallen by the wayside. Imation, still active today, is owned by O-Jin Corp., a Korean technology company that basically bought it for the its trademarked name.

Five Unusual Types of Products 3M Developed Over the Years

Bondo: While not developed under 3M’s roof, the Bondo brand of automotive body filler, essentially a putty designed to fill in holes and cover visual imperfections, has been owned by 3M since at least 2007. Much like Post-its and Scotch Tape, it has become a generic term for the product line it serves.

Petrifilm: You know petri dishes, the containers used to allow bacteria to grow in a lab? Yep, 3M came up with a better version of them, in the form of Petrifilm, an easy-to-deploy platelike product developed by the company’s food-safety department in 1984. The technology has become hugely important in testing for potential food-safety concerns.

Tartan track: You know how Astroturf is commonly used in sports stadiums as a replacement for grass? Tartan track is sort of the track-and-field version of Astroturf , originally designed for horse tracks. One strange element of the Tartan track story is the fact that the original formulation used mercury, making it much more dangerous than it needed to be. (This kind of problem would later be a theme for 3M, a major chemical manufacturer.)

The typodont: This weirdly named device, associated with dentistry, is essentially a plastic model of the mouth and teeth, intended to make it easier to explain what is happening in a person’s mouth. While 3M didn’t invent the typodont, which has existed since the late 19th century, it is one of the 60,000 products the company makes.

Wind-vortex generators: In 2016, 3M developed a technology to help wind turbines generate airflow more optimally to ensure they work better, in partnership with Smartblade. It’s essentially a piece of carefully placed, high-quality plastic that, when placed correctly, increases energy production on turbines by 2 to 3 percent—a boost that adds up.

Much like its one-time competitor Memorex, Imation is a technology ghost kitchen. Its former corporate parent 3M, meanwhile, has a market cap of $51.33 billion at the time of this writing.

3M’s Magnetic Legacy

In a lot of ways, I think 3M’s persisting deep association with computing, despite the fact that the company left the field decades ago, comes down to the fact that it had a very recognizable logo design during its computer heyday.

My first experience with 3M was seeing its bright red logo on floppy disks used in classrooms with Apple IIe computers in the late 1980s and early ’90s. 3M was instantly recognizable among those responsible for creating the disks we needed to load up Number Munchers and Commander Keen, and as a result, its name is forever imprinted into the brains of retro-tech nerds the world over. It is a memory that gives me warm feelings.

But 3M, for a number of reasons, is not a company that carries a lot of goodwill with younger generations. For example, the company is closely associated with the manufacturing of a variety of chemicals, including PFOS (Perfluorooctane sulfonate), a key ingredient in Scotchguard and other water-resistant materials. It’s one of many PFAS (perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl) substances that are believed to be harmful to humans.

The floppy disks that I and other elder millennials associate with a company that was essential to our youthful computing experience are long gone, shuttled away as a non-core business for a giant corporation that is best described as an amalgamation of non-core businesses loosely held together by a logo and backing in chemistry and raw materials.

February 18, 2024

Buy a Refrigerator in 1926 (Click on the link to see a short from the silent screen era)

[Theater commercial–electric refrigerators]. Buy an electric refrigerator

Video Player

00:00

01:00

No polyethylene food wrap back then! My Grandfather sold appliances to local stores as an employee of the electric company in Iowa. It was a pull through to get more people using electricity. Times have changed!

Enjoy

January 29, 2024

Who Remembers Company Watches?

The old time way of rewarding years of service. This was from Dow . . . Probably worth $1,000 bucks on Antiques Roadshow!!!

November 14, 2023

Fall PFA Highlights

Polyurethane Foam Association Fall Meeting Addresses

Sustainability, Industry Innovation

Gollnitz and Khalil Inducted Into Flexible Polyurethane Foam Hall Of Fame

TORONTO, ONTARIO (November 14, 2023)— Sustainability was at the forefront of the

Polyurethane Foam Association’s Fall

Meeting recently in Toronto.

Top industry executives, EHS specialists,

scientists, marketers, and regulatory analysts

met at the Omni King Edward Hotel for

networking sessions and presentations

covering everything from European end-of-

life requirements to irradiation of

polyurethane foam to yield 3-D printing

resins.

PFA’s Industry Issues Session provided

updates on key markets in the flexible foam

industry, including bedding and carpet

cushion. Additional presentations addressed

legal and regulatory developments,

isocyanate research projects, trade

remedies, and more.

In the Technical Program on the following day, presentations covered foam making equipment

and process controls, biocontent and recycling of automotive foam in Europe, inclusion of lignin

and soy polyols into foam formulations, upcycling of EOL foam into 3-D printing resins, and the

Virginia Tech/Arizona State closed loop recycling project.

Awards: Bill Gollnitz of Plastomer Corporation (L) and Dr. Hamdy

Khalil of Woodbridge Group (R) were inducted into the Flexible

Polyurethane Foam Hall of Fame.

Chip Holton of NCFI

Polyurethanes (Center) was presented with PFA’s Lifetime

Achievement Award.

Chip Holton of NCFI Polyurethanes, PFA’s President, recognized new PFA members including

Reticulatus, Ingenieria Del Poliuretano Flexible, S.L., and PCC Rokita. He noted that since the

lifting of pandemic restrictions, 23 new companies have joined PFA.

“PFA continues to be a very effective voice for the flexible polyurethane foam industry,” Holton

noted. “PFA frequently reminds us that industry advocacy is much stronger as a group rather

than as individual companies; PFA also provides an exceptional forum for the exchange of

knowledge and critical industry information.”

As a highlight of the meeting, two long-term veterans of the industry were inducted into the

Flexible Polyurethane Foam Hall of Fame. The Hall of Fame was established to honor the

leaders and innovators. It serves as an information source for future industry members and

researchers regarding the contributions of individuals and companies who have led the growth

and betterment of the flexible polyurethane foam industry in North America.

Bill Gollnitz, Technical Director of Plastomer Corporation, and Dr. Hamdy Khali, Senior

Technology Advisor for Advanced Technologies and Innovation at Woodbridge Foam

Corporation, became the latest inductees, making a total of 35 individuals and companies

honored.

Gollnitz has more than 51 years’ experience in the flexible polyurethane foam industry. For

nearly 30 years, he has been Technical Director at Plastomer Corporation. Prior to that, he held

group management positions at ARCO Chemical Company and Olin Chemical. He began his

career in the foam industry with Firestone Foam, working as a special assistant to Firestone

President Bob Hay, a founding member of PFA and also a member of the Flexible Polyurethane

Foam Hall of Fame.

He has a deep understanding of how chemistry, manufacturing and suppliers can work together

to advance the polyurethanes industry, and developed a reputation for being able to oversee the

construction of flexible foam manufacturing plants from concept to full scale production. He is a

Past President of PFA, and currently serves on PFA’s Executive and Technical Committees.

“Every time there’s a threat to the industry, be it technical or regulatory, PFA has met it head on.

And I’m sure that’s going to continue in the future,” Gollnitz said in his acceptance speech. He

also expressed gratitude for the education tools PFA has developed to attract young professionals

to the industry, and to assist in continuing education of those who have made flexible foam their

careers.

Dr. Khalil pioneered the introduction and commercialization of renewable materials into the

polyurethane chemistry used in interior automotive parts manufacturing. Under his guidance,

Woodbridge became one of the early adopters of green technologies using biobased polyols.

Khalil also played a leading role in ongoing efforts to harmonize OEM specifications for VOC

emissions from plastics in auto interiors.

He served on the Board of Directors of the Ontario Bio Auto Council, and the Center for

Research and Innovation in the Bio Economy (CRiBE). He acted as an advisor to the National

Research Council of Canada on renewable and sustainable materials technology. Dr. Khalil

received the Outstanding Leadership from the Center For the Polyurethane Industry (CPI), and

the Technical Leadership Award from The Nano Division of the Technical Association for the

Pulp and Paper Industry (TAPPI). He was selected to the Advisory Panel For Arbora Nano for

the Advancement of Lignocellulosic Products. Dr. Khalil received the “Le Sueur Memorial

Award” from the Society of Chemical Industry for Outstanding Industrial Contribution.

His passion is in mentoring a new generation of scientists and engineers.

“Polyurethane is the most versatile polymeric system, and it has been serving humanity in more

applications than any other material known to mankind,” Khalil noted. “However, we have many

challenges. Our industry needs to be aggressive in innovation and building partnerships with

institutions and universities. There is much yet to discover about the potential of polyurethanes.”

After the Hall of Fame inductions, outgoing PFA President Holton was presented with PFA’s

Lifetime Achievement Award.

“All of us in the association appreciate Chip’s leadership over the last seven years,” said Russ

Batson, PFA Executive Director. “Chip has the unique ability to analyze a challenge and focus

everyone on the critical elements, so that we can decide on the most sensible pathways forward.”

Dr. Mojgan Nejad won the Dr. Herman Stone Technical Excellence Award. Her presentation,

“Sustainable PU Flexible Foams: Utilizing Renewable Materials from Biomass and Soy,” was

voted best by those attending the Technical Program. The award is named for Dr. Herman T.

Stone, who served as PFA’s first Technical Director. In 2007, Dr. Stone was inducted into the

Flexible Polyurethane Foam Hall of Fame.

The Polyurethane Foam Association is a trade association founded in 1980 to help educate foam

users, allied industries and other stakeholders. PFA provides facts on environmental, health and

safety issues and technical information on the performance of flexible polyurethane foam (FPF)

in consumer and industrial products. FPF is used as a key comfort component in most

upholstered furniture and mattress products, along with automotive seating, carpet cushion,

packaging, and numerous other applications.

To learn more, visit www.pfa.org.

May 5, 2023

Stockmeier Urethanes USA Celebrates 20 Years

STOCKMEIER Urethanes USA, Inc. Celebrates Its 20th Anniversary

Clarksburg, WV – May 4, 2023 – STOCKMEIER Urethanes USA, Inc announces

its 20 th anniversary this month as a specialty polyurethane systems

manufacturer in the United States.

The STOCKMEIER Urethanes USA site in Clarksburg, West Virginia was

purchased in 2003. In 2005, the development and production of

polyurethane coatings, adhesives, sealants and elastomers for the

industrial and sports & leisure industries began. At that time, there were

just eight employees: today, the Clarksburg site employees over 75

consisting of researchers, laboratory technicians, production operators, a

sales force and other important team members.

CEO and President Christian Martinkat states, “STOCKMEIER Urethanes

USA has experienced phenomenal growth in its 20-years of existence here

in Clarksburg.”

Choosing Clarksburg for the new site was the right decision, said Martinkat.

“The West Virginia Economic Development Authority, the West Virginia

Manufactures Association, local government and many others with whom

we work with have always listened to our concerns, needs and visions.

Then and now, we know we made the right decision being here in the

Mountain State.”

When the company opened the site in America, it was a brand-new

company and they only brought with them a couple customers they were

previously selling to in Germany. “We literally started from scratch,” stated

Martinkat. “Since our inception here, we have expanded our product

portfolio, entered new markets, installed numerous production and lab

equipment, streamlined processes, improved IT technology and completed

many renovations to our facilities.

All these continuous improvement projects have allowed us to be even better at what we do and provide, and

we are not done yet.”

Melissa Martinkat, US Chief of Staff, added that beyond those

improvements, the company puts a large focus on supporting local

communities by participating in fundraisers, donating to charities and

scholarships, sponsoring events and participating in educational programs

in schools.

STOCKMEIER Urethanes USA has also been on their journey to continue

being an environmental steward by being members of and participating in

the American Chemistry Council’s Responsible Care ® program.

In this program, there are set standards which must be met that

demonstrates the company’s commitment to the health and safety of their

employees, the communities in which they operate, and the environment.

Over the last 20 years, the company’s dedication to quality, innovation and

superior customer service has allowed them to become a trusted supplier

of polyurethane products. Martinkat states the company will continue to be

a family owned and operated company with a strong commitment to their

customers, employees and partners for many years to come.