History

May 15, 2024

F. Quinn Stepan

Birth: October 24th, 1937

Death: May 13th, 2024

F. Quinn Stepan OBITUARY

The world lost an extraordinary man on May 13, 2024. F. Quinn Stepan died peacefully in his home of 60 years.

The beloved husband of the late Jean “Snowy” Stepan (nee Finn) and devoted son of the late Alfred Charles and Mary Louise Stepan lived his life for others. Quinn Stepan had many passions, his first was his love for his wife, Snowy. They were married for 63 years and raised eight children.

He was the loving father of Jeanne (Rob) Schoder, Quinn (Debbie) Stepan Jr., Jennifer (Jim) Beqaj, Lisa (Tim) Hackett, Colleen (Jay) Tulimieri, Alfred (Candice) Stepan and Richard (Heather) Stepan and the late Todd Stepan. Cherished grandfather of Theresa (Joe) Stepan Dumais, Meghann (John) Stepan Kelly, Quinn P. Stepan, Robby (Taylor) Schoder, Mari Schoder, Scott (Mary) Schoder, Charlie Schoder and the late Michael Schoder, Jack, Sam, and Sarah Beqaj, Grace, Francie, Timmy, and Johnny Hackett, Quinn, Jeanne, Libby, and Jack Tulimieri, Spencer Stepan, and Haley, Finn, and Brenna Stepan. He also was blessed to be the fond great grandfather of Olivia, Hudson and Miles Schoder, Faye and Scott Schoder, Colin, Katelyn, Lilly and Andrew Dumais, Mac, Step, Walt and Rhetta Kelly, and Quinn H. Stepan.

Quinn Stepan was born in 1937 in the middle of an economic recession, the tough times would influence his lifestyle choices. He was the third child of Alfred and Mary Louise. He was a proud member of the Winnetka Stepan family with four brothers and two sisters. He grew-up on the Village Green, sitting on the cannon, running in the Fourth of July races and swimming in Maple Street Beach.

Quinn and Snowy Stepan hosted the extended family for the Turkey Bowl and Thanksgiving for more than 100 people, for four decades. Traditions were important to Quinn, he believed that gatherings created the opportunity to build connections and strengthen bonds between people. Quinn was the dear brother of Stratford (Judy) Stepan, Charlotte (Jim) Stepan Shea and John (Bonnie) Stepan and Brother-in-law to Richard Wehman and sister-in-law to Nancy Leys Stepan. His sister Marilee Stepan Wehman and sister-in-law Ann Ruppe Stepan, brothers Alfred Stepan and Paul Stepan predeceased him.

Quinn attended Faith, Hope and Charity, Loyola Academy, and then the University of Notre Dame. He cultivated life long friendships across each of these institutions. After Notre Dame, he served in the Army and moved with his young family to Michigan, Texas and New Jersey. Eventually they found their way back to Winnetka, earning an MBA at the University of Chicago, residing in the shadow of Faith Hope for the last 60 years.

He loved Winnetka and Lake Michigan. Quinn never forgot the foundation of his Catholic education and he firmly believed in its importance. He would serve as the Chairman of the Board for both Loyola Academy and Woodlands Academy. He spent decades on the Notre Dame Liberal Art Council and was an ardent supporter of Big Shoulders and the Stepan Scholars program at the Our Lady of Grace parochial school. He believed Catholic education was important to build people of good character and sound mind. He definitely valued a liberal arts background, he said it was important for students to develop their thinking and writing skills. He funded the Stepan Economic Chair at Notre Dame to coax the best professors to stay in the College of Arts & Letters instead of decamping to the Business Schools.

He shared his leadership and management skills tirelessly to help these institutions flourish.

Quinn Stepan will also be remembered for the company he lead. His Team took the company his father founded in 1932 and made it a global powerhouse. When Quinn joined Stepan Company in 1961, net sales were $17.3 million and net income was $1.3 million with 3 domestic industrial plants. Today, it is a global company with 22 plants in 12 countries with 2 billion dollars in sales that employs more than 2400 people.

He loved going to work everyday at Stepan. He built a culture of idea sharing, congeniality and excellence. He ate lunch in the company cafeteria so he could visit with the troops. He was recognized as an industry leader and was honored with the Elva Walker Spillane Distinguished Service Award in 2010.

Family will always be the greatest legacy of Quinn Stepan. His family was his top priority. He loved everyone, he cared deeply about their well-being, their education, their futures and their passions. He was the catalyst for incredible family events – holiday celebrations, travel escapades that included European and American driving tours, Mediterranean boat cruises, golf outings, ski trips, Olympic experiences, African safaris, early trips to India and China. He wanted to share the joys of travel with others and wanted to create a wonder for the vastness of the world.

He chronicled all these good times – the games he attended, the beautiful places visited, graduations, baptisms etc.… It was not uncommon for relatives to be jockeying for position on his photo shelves. He loved his photos and being surrounded by the smiles and love of the family he had built. He was dedicated, steadfast and resolute. We knew that we always had a cheerleader in our corner. It is these memories that will provide comfort. He will be deeply missed by his family, friends and colleagues. Hopefully, all can take the lessons of Quinn’s well lived life and move forward to be the catalyst for change to make our world a little better.

Visitation Thursday, May 16, 2024, 10:00 a.m. CDT at Saints Faith, Hope & Charity Church, 191 Linden Street, Winnetka, IL 60093, it will immediately be followed by a 11:00 a.m. Funeral Mass. To virtually attend the funeral Mass, visit F. Quinn Stepan’s obituary page on donnellanfuneral.com to access the link to the live streaming. The family invites you to a reception immediately following Mass in the Saints Faith Hope & Charity Parish Hall. Interment private All Saints Cemetery, Des Plaines, IL. In lieu of flowers, memorials may be made to either: Big Shoulders Fund. Info: donnellanfuneral.com or 847-675-1990

April 30, 2024

3PL History

Over the past decade, C.H. Robinson lost its moat to innovation and competition

Can it evolve quickly enough to satisfy Wall Street?

Craig Fuller, CEO at FreightWaves

· Monday, April 29, 2024

C.H. Robinson (Nasdaq: CHRW), the largest trucking freight brokerage, is in a challenging spot that isn’t strictly due to the Great Freight Recession. Its stock is trading near the lows of the COVID lockdown (closing price on April 26 was $70.22; the COVID low was $63.91), with investors asking tough questions about the company’s long-term prospects.

For three and a half decades, C.H. Robinson’s position was uncontested. It was in an enviable position — it had information and access to fleets that no one else did. After all, with the largest number of offices around the country and the largest network of carriers, almost no one could compete with Robinson’s pulse on the market or connection to fleets.

Early on, this information and trading arbitrage became C.H. Robinson’s unfair advantage.

However, other freight brokers emerged, and the share of freight that brokers handled grew faster than C.H. Robinson’s business.

Less than a quarter-century ago — in 2000 — freight brokerages handled only 6% of all trucking freight. Today, FreightWaves estimates that 25%-30% of freight is handled by 3PLs; others have suggested that the figure is more than 50%. Regardless, it’s a huge number.

Brokerages gained market share by taking freight from the largest asset truckload carriers, playing the role previously reserved for companies with trucks.

Shippers used to be reluctant to give freight to companies that didn’t own their own trucks. Still, they eventually realized that freight brokerages provided unparalleled flexibility and could offer rates that shifted as the market did (freight costs are massively volatile).

Because brokerages were not constrained by fleet size, they could handle surges much easier than asset-based carriers. In that regard, a brokerage can provide a superior product compared to a single-source truckload provider.

Those circumstances have caused large over-the-road truckload providers to struggle for years. It is not just freight brokerages taking share; intermodal (railroads) are also eating their lunch.

A few companies like J.B. Hunt, Werner, and most recently, Covenant, saw these changes coming. They largely moved away from their dependence on the for-hire truckload market.

Others failed to pivot fast enough — Celadon, CFI, U.S. Xpress, Interstate, etc. — and each paid dearly.

In addition, shippers benefited from the fact that brokerages were faster than the fleets about investing in technology and customer success initiatives.

From 2000 to 2015, the industry saw the scale of startup or small brokerages explode (Brokerage 2.0): TQL, Echo, Coyote, Command, Access America, Nolan, GlobalTranz and many others grew exponentially.

This caught the attention of private equity (PE) firms, corporations, and even UPS — they all bought into the belief that the freight brokerage market was ripe for consolidation.

The Brokerage 2.0 players sold out, and middle management at those firms left and started their own versions of what we’ll call Brokerage 3.0.

Meanwhile, technologies emerged that eroded Robinson’s information and fleet access advantage.

Emerging firms like Arrive, Molo and Steam popped up, and hundreds of others were created, requiring little more than a computer, an MC, and a load board account. These firms grew very quickly — understanding that the secret to freight brokerage was recruiting new brokers and creating a dynamic sales culture — something that “stuffy” corporates, PE and UPS would never understand.

The new firms cleaned the clocks of the incumbents.

PE firms and strategic acquirers soon learned that there was little differentiation between the various freight brokerages, and it was hard to retain talent unless the management teams stayed intact (which is hard to do after they’ve sold out).

Then, the most damning part of the story took place: Silicon Valley discovered freight brokerage. Startups like Convoy and Uber Freight were funded — and all focused on blitzscaling. Even Amazon joined the party, leveraging its vast resources and huge freight spend to take an additional share.

In the U.S., Amazon moves more freight through its network than FedEx.

Early on, these startups tried to achieve critical mass, offering heavily discounted pricing to “buy share.”

And they did. The digital natives grew exponentially without concern for short-term profits. However, many of those same firms have found profit elusive or worse.

At the same time, tech vendors made it easier for new entrants to join the industry and existing players to scale quickly.

DAT Rateview, Truckstop Rate Insights, SONAR and FreightWaves removed Robinson’s information advantage — now, everyone understood what was happening in the market in near real time.

Public and private load boards (DAT, Truckstop, Loadboard123), digital matching apps (J.B. Hunt 360, Loadsmart, Emerge), Trucker Tools, and others took away Robinson’s capacity access advantages. At the same time, systems like Mercury Gate, Ascend TMS, Macropoint, P44, FourKites and Transflo destroyed Robinson’s advantages in system infrastructure that enabled the brokerage to scale so quickly.

Perhaps the biggest blow to C.H. Robinson’s business model is the emergence of payment networks like TriumphPay that make it seamless for brokerages to fund growth without needing large balance sheets.

Now, anyone can start or grow a freight brokerage with little upfront capital and play at the same level (or even better) as C.H. Robinson.

After successfully fending off the pressures of competition for three decades, C.H. Robinson finally gave in.

Bob Biesterfeld, the former CEO of C.H. Robinson, declared in 2019 that the company would protect its market share by investing $1 billion in new technology.

But it was too late. Robinson had been losing market share, but this was hard to see because of the growth of the underlying market. As long as the freight brokerage market grew, few would realize that C.H. Robinson’s business was under real stress.

Then, the freight market exploded during COVID. Robinson made a fortune during the peak COVID cycle, handily beating analyst estimates like everyone in the space. However, that peak cycle turned, followed by the Great Freight Recession — one of the biggest and most painful downturns in freight market history.

Although Robinson replaced its CEO, the new CEO can do little to fend off the inevitable decline of its core business.

In recent months, FreightWaves has received reports of many veteran brokers leaving the firm, something that was unfathomable just a few years ago. Sources told FreightWaves that the departures were caused by compensation restructuring initiatives and a change in the company’s operating culture.

Margins are under pressure from the Great Freight Recession, which is now in its third year, and the cutthroat competition of thousands of freight brokerages all bidding on the same loads.

Sources have told FreightWaves that Robinson’s new management wants to change the company’s cost structure and has pursued a series of changes to its compensation structures to change the unit economics of the business. These changes have been controversial and unpopular; some veteran reps with decades of tenure have left Robinson to protest the company’s new operating culture.

However, the company must reduce operating expenses to offset the impact of declining brokerage margins.

There are few good short-term answers for C.H. Robinson.

Competition is only going to increase. Robinson’s one-time advantages are largely gone, killed by innovation and direct competition. Its leadership has little choice but to address compensation packages representing the largest operating cost at freight brokerages. But, as noted above, as those changes occur, the company will continue to lose some of its most successful sales and carrier reps. Shippers are likely to leave as a result, as often, the personal relationship with the sales and customer service teams is what keeps the shipper from moving to a competing broker.

Worse still, as a public company, all of Robinson’s challenges are visible to everyone, including competitors, employees, and customers.

A huge business model reset with some long-term thinking is required, but that may be difficult for a publicly traded company to satisfy investor expectations every quarter.

April 2, 2024

Who Remembers Floppy Disks?

The Rise and Fall of 3M’s Floppy Disk

The high-profile creator of magnetic media gave it up nearly three decades ago

8 hours ago

10 min read

3M’s floppies were not unique, but they were emblematic of an early computing era.

IEEE Spectrum

3m floppycomputer historyaudio tapemasking tape

A version of this post originally appeared onTedium, Ernie Smith’s newsletter, which hunts for the end of the long tail.

If you ask the average person what the company 3M does, odds are if they have a few gray hairs hanging out on their scalp, they might say that the company makes floppy disks. Now, this was once true, but if you look on 3M’s own website, you will see no mention of this legacy—it’s a firm that sells abrasive materials, adhesive tapes, filters, films, personal protective equipment, and medical equipment. (Younger people, if they recognize 3M, it’s probably because of Post-it notes, or more recently its N95 masks)

Floppies have had a surprisingly long life—in January 2024, Japan announced it will no longer require floppy-disk copies of government submissions. But 3M got out of the data-storage business about 28 years ago, when it transferred its floppy disk manufacturing to a spin-off called Imation. Imation is still around, under the name Glassbridge Enterprises, but with a much smaller profile.

3M’s spin-off, Imation, continued producing floppy disks after 3M itself left the business. IEEE Spectrum

Even with that said, those gray-hairs will frequently claim that of the many makers of floppies out there, 3M made the best ones. Given that, I was curious to figure out exactly why 3M became the most memorable brand in data storage during the formative days of computing, and why it abandoned the product.

How 3M Became a Key Innovator in the Production of Magnetic Data Storage

Now, to be clear, 3M did not invent magnetic storage—that was done by Austro-German engineer Fritz Pfleumer, in 1928. He created audio tape, a recording medium that started as broad strips of paper coated with iron-powder granules, and eventually moved to less-fragile cellulose acetate with help from what would become another big name in floppy disks, BASF. At first, the innovation didn’t spread outside of Germany because of World War II.

Nor was 3M the first company to popularize magnetic media— that was Ampex, which commercialized the tape recorder in the late 1940s. That was the point when magnetic tape turned into a major innovation in the world of music—one that, famously, Bing Crosby got to first because he gave financial support to Ampex. Incidentally, Ampex’s later spinoff, Memorex, represented Silicon Valley’s first true startup.

“Of all the businesses 3M has shed over its 100 years, the two seminal decisions that people point to as most significant involved the sale of 3M’s Duplicating Products business to Harris Corporation in Atlanta, Georgia, and the spin-off of 3M’s data-storage and imaging-systems businesses in 1996 creating a new company called Imation in Oakdale, Minnesota…”

Before World War II, one company did attempt to manufacture a tape recorder in the U.S. based on Pfluemer’s magnetic-tape invention. That firm, the Brush Development Co., had developed a device called the Soundmirror, produced by a Hungarian inventor named Semi J. Begun, who was likely something of a competitor to Pfleumer: Also a German, he had moved to the United States and developed a steel-based magnetic tape. The invention was used by the U.S. military during the war, and the company revisited the idea immediately after. But, it needed someone to manufacture magnetic tape for it to use.

As author David Morton noted in his 2006 book Sound Recording: The Life Story of a Technology, 3M was one of the best-suited companies on the market to help Brush out. That’s because the groundbreaking work that the company had done to develop pressure-sensitive adhesive tape was an essential element of making magnetic tape effective.

3M’s adhesive-tape technology transferred readily to magnetic tape. 3M

Strangely enough, Richard Gurley Drew, the inventor of much of 3M’s tape technology, was a musician—he played banjo in a local orchestra—when he took a job with the company. He probably didn’t realize he was inventing a key element of 20th-century recording technology when he observed that auto body shops needed a way to “mask off” areas of vehicles that were being whittled down with sandpaper, but his observation would prove useful to the invention of masking tape.

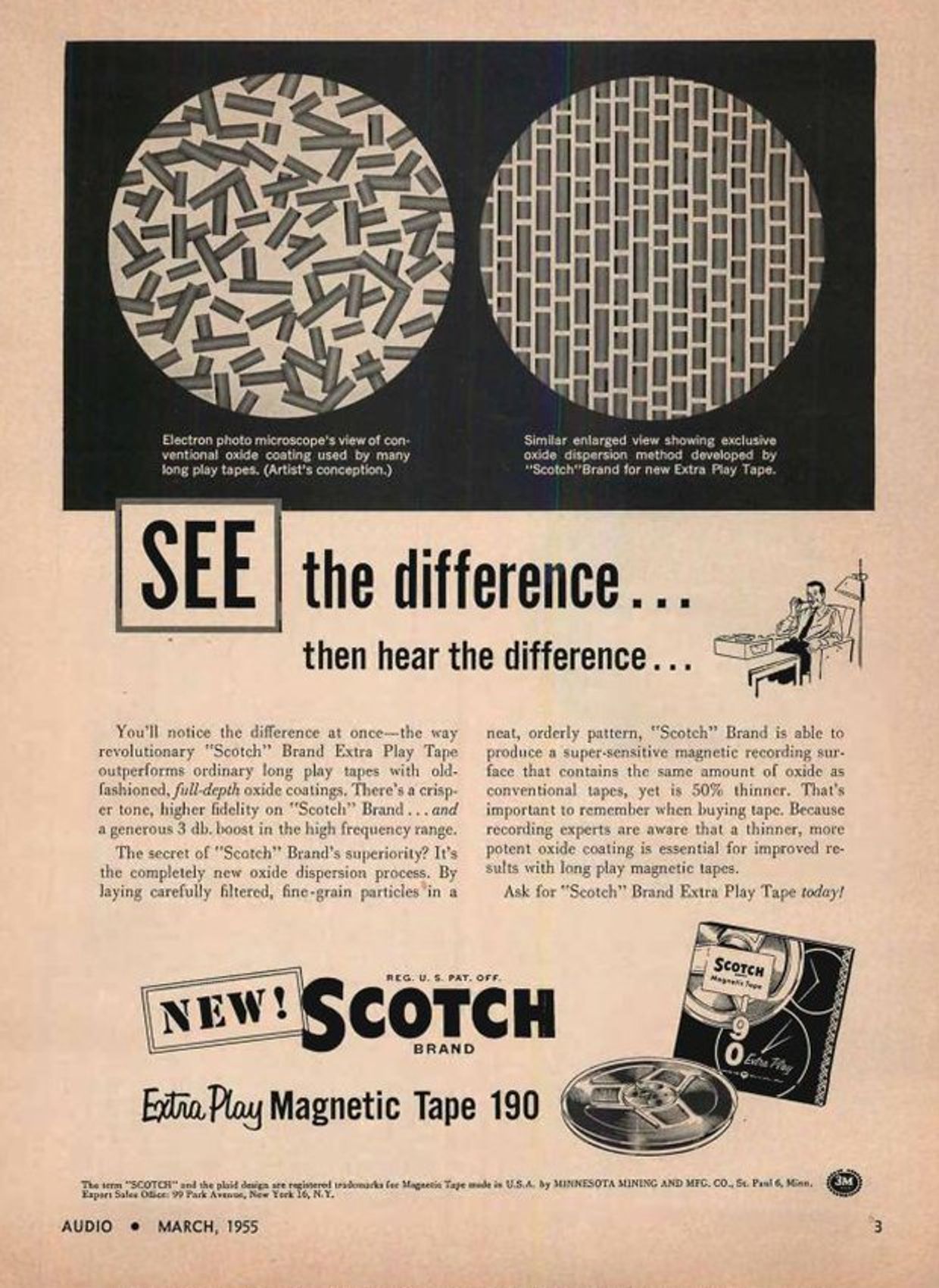

In the mid-1950s, 3M advertised its Scotch audio reel-to-reel tape.Audio Magazine/Internet Archive/Scotch

In the mid-1950s, 3M advertised its Scotch audio reel-to-reel tape.Audio Magazine/Internet Archive/Scotch

As Smithsonian Magazine notes, the formulation he developed, combining cabinetmaker’s glue with glycerin, proved to be just the right level of easy-to-remove adhesive that it became an out-and-out phenomenon. You might know his invention, developed in 1925, as Scotch Tape.

In 1930, he followed it up with another invention that was even more amazing—tape made from cellophane, which by its nature was totally transparent. Another 3M employee developed the tape dispenser, and the two inventions reshaped offices the world over.

So, when Brush looked to others to produce its recording medium, 3M was well positioned to help out due to magnetic tape’s similarity with its Scotch Tape. Brush eventually moved to other manufacturers, like Dupont. But the experience led 3M to continue developing metal-oxide tape technology, leading to the creation of the Scotch 111 reel-to-reel tape, which was one of the most popular types used in recording studios throughout the 1950s, according to the Museum of Magnetic Sound Recording.

I admittedly have long had a fascination with these reel-to-reel tapes. A number of years ago, back when I lived in Milwaukee, I found a couple of blank reel-to-reel tapes created by 3M using the Scotch name. I bought them from a junk store, and maybe paid $2 for them. They managed to follow me through three states and five cities, and now sit on my intentionally organized pile of junk. Based on my analysis of the container and the logotype it uses, they date to the mid-1960s or earlier. (No, I have not tried to record on them.)

I’ve owned this blank Scotch 150 reel-to-reel tape for nearly 20 years. It is 50 to 60 years old. Ernie Smith

For years, 3M’s reel-to-reels had one of the strongest reputations in the music industry; they were built to be of superhigh quality. But you might be wondering, how did 3M make the leap from reel-to-reel tape to floppies? It feels like just as strange a leap as a masking tape company developing reel-to-reel audio tape.

But, again, it happened.

How 3M’s Tapes Went From Music to Data

3M didn’t develop the floppy disk drive, either. IBM did, and Shugart Associates further improved it by making it small enough for regular users.

3M manufactured a signature 5.25-inch floppy disk. IEEE Spectrum

But 3M, much as with mechanical tape, was well positioned to improve on it, leveraging its skills with mechanical media in the budding computing industry. In a way, 3M came to media manufacturing from the opposite direction than its disk-selling competitor Memorex did. Memorex started with computers and gradually came to develop and improve tape-based technology, which eventually evolved into floppy disks. On the other hand, 3M started with the raw materials and the manufacturing processes, and combined those into computing’s greatest commodity item, the floppy disk.

3M got into the floppy disk market around the fall of 1973. It was not the only manufacturer of disks out there—some names from this era include Verbatim, Control Data, Dysan, and BASF. Most of these companies started with computing technology—for example, Dysan worked closely with Shugart Associates on the 5.25-inch floppy. But 3M wasn’t alone in starting with the raw materials. BASF, a German chemical manufacturer, has a somewhat similar corporate history and logo design to fellow thick-Helvetica enthusiast 3M. (Though 3M obviously never associated with the Nazis during World War II, so there’s that.)

3M branched out beyond standard floppy disks with a variety of magnetic-tape storage media.ComputerWorld/Google Books/3M

3M branched out beyond standard floppy disks with a variety of magnetic-tape storage media.ComputerWorld/Google Books/3M

3M didn’t rest on its laurels with the floppy disk either, and tried to push the technology further, most notably with Floptical disk technology, which Jim Adkisson, who helped create the 5.25-inch floppy at Shugart Associates, developed in the 1980s. A partnership of 3M, Maxell, and Iomega created the Floptical disk, which could hold 20 megabytes of data on something that looked a lot like a 3.5-inch floppy. Unfortunately the floptical disk flopped, losing out to products like Iomega’s iconic Zip drives.

3M also worked in more specialized media, developing high-capacity optical disks that fit into standard floppy and optical disk mechanisms, as well as high-end tape drives intended for the server room rather than your cassette player.

In many ways, 3M was out front on one of the most important elements of computing and was making huge profits from it. But by the end of 1995, those days were done. What changed?

https://www.youtube.com/embed/bOHKgENMcGQ?rel=03M advertised its floppy disk as more reliable than the competition in no uncertain terms.

What Led 3M to Kick a Multibillion-Dollar Business to the Curb

By 1995, 3M’s magnetic-media arm had evolved into a US $2.3 billion business, according to Time, which made it a significant chunk of 3M’s overall offering.

But at that time, high technology— especially consumer technology—was starting to look like a bad bet for legacy companies. This was around the same period that AT&T, still smarting from misadventures like the EO Personal Communicator, spun off Bell Labs as Lucent Technologies.

3M’s story, in its own words, suggests a similar crisis of culture. In A Century of Innovation, a book published by the company in 2002, around the time of its 100-year anniversary, the company compared the creation of the spin-off, which it called “the most wrenching decision in its history,” to that of its determination eight years earlier to sell its Duplicating Products Division, which sold copying machines:

Of all the businesses 3M has shed over its 100 years, the two seminal decisions that people point to as most significant involved the sale of 3M’s Duplicating Products business to Harris Corporation in Atlanta, Georgia, and the spin-off of 3M’s data-storage and imaging-systems businesses in 1996 creating a new company called Imation in Oakdale, Minnesota, near 3M headquarters. The two decisions have several elements in common—both involved businesses that 3M created and, in fact, ranked number one in the marketplace for decades. They were “homegrown” businesses—largely created within 3M and commercialized and built with the energy of many internal sponsors and champions. The businesses were risky because the products were based on pioneering technologies. They not only changed the basis of competition; they also created all new, global industries. The businesses were highly profitable for decades, and they represented a significant share of the company’s total annual revenues. They also produced many of 3M’s next generation of leaders.

So what happened? Essentially, despite the company’s success working in industrial and professional settings, doing things for consumers like producing videotapes, floppy disks, and cassettes meant moving out of its comfort zone. These products, initially developed for businesses, grew so popular that they suddenly needed to be available at every big-box store and drugstore alike, and, Post-its aside, retail was not a fit for the kind of company 3M was.

But more significantly, other companies were simply better at undercutting, and per the corporate biography, that required some tough decisions to be made:

While it sold its products for little or no profit, its competition sold their products for even less. Even though the consumer business had huge growth potential, 3M had little experience with a low-cost, low-profit-margin model.

The markings were clear—exit this business, even though 3M invented it. To stay in the “dog fight” meant 3M had to invest enormous amounts of money in order to remain the low-cost producer, with no assurance that profit margins ever would improve. “Exiting it was the right decision,” [former senior vice president Al] Huber said.

Seeing what came after, it’s hard to disagree. While floppies were still a significant medium in the mid-1990s, it was obvious that they would not be enough capacity for the next generation of data hoarders. It would only be a couple of years before Apple would put the first dagger in the heart of the floppy disk with the iMac, breaking with tradition by releasing a personal computer in 1998 with no built-in floppy disk drive.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/3qkQi3zZVhg?rel=0Imation carried on a floppy-disk ad campaign through the late 1990s.

That was a harbinger of what was to come. Within a decade of the decision, floppy drives, compact cassettes, and videotapes—the three key elements of 3M’s move into consumer-driven magnetic media—had fallen by the wayside. Imation, still active today, is owned by O-Jin Corp., a Korean technology company that basically bought it for the its trademarked name.

Five Unusual Types of Products 3M Developed Over the Years

Bondo: While not developed under 3M’s roof, the Bondo brand of automotive body filler, essentially a putty designed to fill in holes and cover visual imperfections, has been owned by 3M since at least 2007. Much like Post-its and Scotch Tape, it has become a generic term for the product line it serves.

Petrifilm: You know petri dishes, the containers used to allow bacteria to grow in a lab? Yep, 3M came up with a better version of them, in the form of Petrifilm, an easy-to-deploy platelike product developed by the company’s food-safety department in 1984. The technology has become hugely important in testing for potential food-safety concerns.

Tartan track: You know how Astroturf is commonly used in sports stadiums as a replacement for grass? Tartan track is sort of the track-and-field version of Astroturf , originally designed for horse tracks. One strange element of the Tartan track story is the fact that the original formulation used mercury, making it much more dangerous than it needed to be. (This kind of problem would later be a theme for 3M, a major chemical manufacturer.)

The typodont: This weirdly named device, associated with dentistry, is essentially a plastic model of the mouth and teeth, intended to make it easier to explain what is happening in a person’s mouth. While 3M didn’t invent the typodont, which has existed since the late 19th century, it is one of the 60,000 products the company makes.

Wind-vortex generators: In 2016, 3M developed a technology to help wind turbines generate airflow more optimally to ensure they work better, in partnership with Smartblade. It’s essentially a piece of carefully placed, high-quality plastic that, when placed correctly, increases energy production on turbines by 2 to 3 percent—a boost that adds up.

Much like its one-time competitor Memorex, Imation is a technology ghost kitchen. Its former corporate parent 3M, meanwhile, has a market cap of $51.33 billion at the time of this writing.

3M’s Magnetic Legacy

In a lot of ways, I think 3M’s persisting deep association with computing, despite the fact that the company left the field decades ago, comes down to the fact that it had a very recognizable logo design during its computer heyday.

My first experience with 3M was seeing its bright red logo on floppy disks used in classrooms with Apple IIe computers in the late 1980s and early ’90s. 3M was instantly recognizable among those responsible for creating the disks we needed to load up Number Munchers and Commander Keen, and as a result, its name is forever imprinted into the brains of retro-tech nerds the world over. It is a memory that gives me warm feelings.

But 3M, for a number of reasons, is not a company that carries a lot of goodwill with younger generations. For example, the company is closely associated with the manufacturing of a variety of chemicals, including PFOS (Perfluorooctane sulfonate), a key ingredient in Scotchguard and other water-resistant materials. It’s one of many PFAS (perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl) substances that are believed to be harmful to humans.

The floppy disks that I and other elder millennials associate with a company that was essential to our youthful computing experience are long gone, shuttled away as a non-core business for a giant corporation that is best described as an amalgamation of non-core businesses loosely held together by a logo and backing in chemistry and raw materials.

February 18, 2024

Buy a Refrigerator in 1926 (Click on the link to see a short from the silent screen era)

[Theater commercial–electric refrigerators]. Buy an electric refrigerator

Video Player

00:00

01:00

No polyethylene food wrap back then! My Grandfather sold appliances to local stores as an employee of the electric company in Iowa. It was a pull through to get more people using electricity. Times have changed!

Enjoy

January 29, 2024

Who Remembers Company Watches?

The old time way of rewarding years of service. This was from Dow . . . Probably worth $1,000 bucks on Antiques Roadshow!!!