The Urethane Blog

Everchem Updates

VOLUME XXI

September 14, 2023

Everchem’s exclusive Closers Only Club is reserved for only the highest caliber brass-baller salesmen in the chemical industry. Watch the hype video and be introduced to the top of the league: — read more

July 2, 2019

FXI’s Philippe Knaub Joins CertiPUR-US Board of Directors

FXI’s Philippe Knaub Joins CertiPUR-US Board of Directors

![]()

![]()

June 28, 2019

Carmageddon Craves Cash-For-Clunkers 2.0 As Average Vehicle Age Soars To Record High

Authored by Wolf Richter via WolfStreet.com,

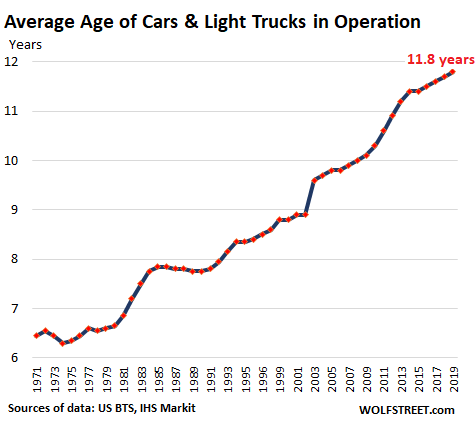

The average age of passenger cars and trucks on the road in the US ticked up again in 2019, to another record of 11.8 years, IHS Markit reported today.

When I entered the car business in 1985, the average age had just ticked up to 7.8 years, and the industry was fretting over it and thought the trend would have to reverse, and customers would soon come out of hiding and massively replace those old clunkers with new vehicles, and everyone would sell more and make more. But those industry hopes for a sustained reversal of the trend of the rising average age have been bitterly disappointed:

This rising average age is largely driven by vehicles lasting longer – an unintended consequence of relentless improvements in overall quality, forced upon automakers by finicky customers in an ultra-competitive market where automakers struggle to stay alive. To make it in the US, they have to constantly improve their products, and stragglers that can’t compete are left unceremoniously by the wayside. US consumers are brutal.

This unintended consequence of rising overall quality contributes to the dreadful industry problem: The US, despite constant population growth, is a horribly mature auto market.

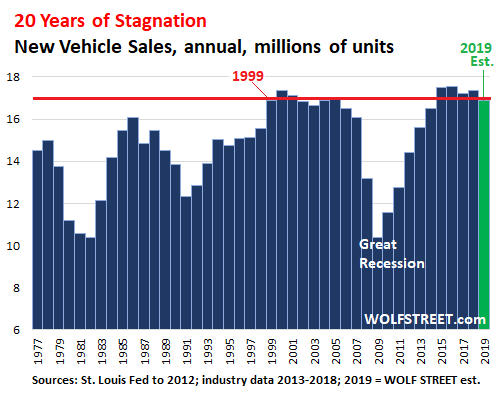

In 1999, so 20 years ago, new vehicle sales reached a record of 16.9 million units. This record was broken in 2000, with 17.3 million units. Then sales tapered off. By 2007, they’d dropped to 16.1 million units. Then the Financial Crisis hit, GM and Chrysler went bankrupt, Ford almost did, and peak-to-trough, sales plunged 40% to 10.4 million units by 2009.

The recovery has been steep, and in 2015, finally the old record of the year 2000 was broken, but barely with 17.48 million units, and in 2016, the industry eked out another record of 17.55 million units. And that was it. Sales have fizzled since then. So far in 2019, the data indicates that sales are likely to fall below 17 million units, according to my own estimates, bringing the industry right back where it had been 20 years ago in 1999:

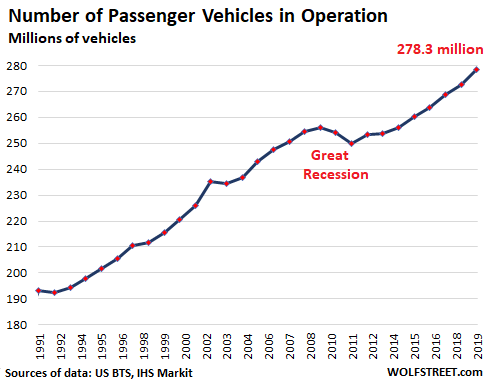

Yet, given the longer average age of the vehicles on the road across the entire fleet, even stagnating sales produce a rising number of vehicles in operation. So it’s not that Americans as a whole have fewer cars – far from it: They have more cars, and those cars are on average older.

The number of vehicles in operation (VIO) in 2019 rose by 5.9 million units from 2018, to a new record of 278.3 million vehicles, according to IHS Markit. In other words, during the 12-month period, about 17 million new vehicles were added to the national fleet; and about 11 million units were removed from the fleet, either by being sent to the salvage yard or by being exported to other countries.

What you see in the chart above is the future supply for the used vehicle market. Used vehicle sales will likely come in just under 40 million units this year – so about 2.3 times the sales volume of new vehicle sales.

The fact that the average age of the vehicles in operation is rising doesn’t mean that all people hang on to their cars longer. On the contrary.

Sure, we drive a car we bought new 12 years ago; it’s in great shape, looks good, the six-figure odometer reading is just a blip, and we’re going to hang on to it because there is no reason to get rid of it. We know other people on the same program. Millions of Americans do that.

But other people have two-year or three-year leases, and this is a booming business. More and more people lease. And when the lease ends, their old vehicle is returned to the leasing company, which owns the vehicle, and which then sells it at auction, where a dealer buys it and then sells it as a used vehicle to a retail customer. These vehicles are only two or three years old, and often in mint condition.

Then there is the huge fleet or rental cars of about 2.2 million vehicles that are turned over every couple of years or so to enter the used-vehicle market, much of it via auctions held around the country.

In addition, there are corporate and government fleets that get turned over at different intervals, and those units end up on the used vehicle market.

So the rising average age doesn’t mean that Americans drive the same vehicle for a longer period of time – though they can, and many do – but that there is a strong market and demand for good older vehicles, and people buy them and drive them for a few more years.

But it is an issue for automakers. They could sell a lot more vehicles – and I mean a whole bunch more – if their vehicles on average reached the end of their life after eight years. But our finicky consumers don’t go for this program anymore. Quality is one of the factors that decides whether an automaker is going to make it or whether it will die.

What’s left for automakers to do to increase revenues in this environment of two decades of stagnating unit sales? A three-pronged industry strategy has emerged: Shift customers to more expensive vehicles, such as from cars to trucks and SUVs; load the vehicles with more goodies each year, such as driving-assist features; and jack up the prices pure and simple.

And automakers have been doing it across the board, which has the effect that for many Americans, new vehicles have become too expensive, and they stopped buying them, which puts further downward pressure on unit sales. But Wall Street, which keeps pushing automakers to go further and further upscale – because that’s where the money is – hasn’t figured this out yet.

https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2019-06-28/carmageddon-craves-cash-clunkers-20-average-vehicle-age-soars-record-high

June 28, 2019

Carmageddon Craves Cash-For-Clunkers 2.0 As Average Vehicle Age Soars To Record High

Authored by Wolf Richter via WolfStreet.com,

The average age of passenger cars and trucks on the road in the US ticked up again in 2019, to another record of 11.8 years, IHS Markit reported today.

When I entered the car business in 1985, the average age had just ticked up to 7.8 years, and the industry was fretting over it and thought the trend would have to reverse, and customers would soon come out of hiding and massively replace those old clunkers with new vehicles, and everyone would sell more and make more. But those industry hopes for a sustained reversal of the trend of the rising average age have been bitterly disappointed:

This rising average age is largely driven by vehicles lasting longer – an unintended consequence of relentless improvements in overall quality, forced upon automakers by finicky customers in an ultra-competitive market where automakers struggle to stay alive. To make it in the US, they have to constantly improve their products, and stragglers that can’t compete are left unceremoniously by the wayside. US consumers are brutal.

This unintended consequence of rising overall quality contributes to the dreadful industry problem: The US, despite constant population growth, is a horribly mature auto market.

In 1999, so 20 years ago, new vehicle sales reached a record of 16.9 million units. This record was broken in 2000, with 17.3 million units. Then sales tapered off. By 2007, they’d dropped to 16.1 million units. Then the Financial Crisis hit, GM and Chrysler went bankrupt, Ford almost did, and peak-to-trough, sales plunged 40% to 10.4 million units by 2009.

The recovery has been steep, and in 2015, finally the old record of the year 2000 was broken, but barely with 17.48 million units, and in 2016, the industry eked out another record of 17.55 million units. And that was it. Sales have fizzled since then. So far in 2019, the data indicates that sales are likely to fall below 17 million units, according to my own estimates, bringing the industry right back where it had been 20 years ago in 1999:

Yet, given the longer average age of the vehicles on the road across the entire fleet, even stagnating sales produce a rising number of vehicles in operation. So it’s not that Americans as a whole have fewer cars – far from it: They have more cars, and those cars are on average older.

The number of vehicles in operation (VIO) in 2019 rose by 5.9 million units from 2018, to a new record of 278.3 million vehicles, according to IHS Markit. In other words, during the 12-month period, about 17 million new vehicles were added to the national fleet; and about 11 million units were removed from the fleet, either by being sent to the salvage yard or by being exported to other countries.

What you see in the chart above is the future supply for the used vehicle market. Used vehicle sales will likely come in just under 40 million units this year – so about 2.3 times the sales volume of new vehicle sales.

The fact that the average age of the vehicles in operation is rising doesn’t mean that all people hang on to their cars longer. On the contrary.

Sure, we drive a car we bought new 12 years ago; it’s in great shape, looks good, the six-figure odometer reading is just a blip, and we’re going to hang on to it because there is no reason to get rid of it. We know other people on the same program. Millions of Americans do that.

But other people have two-year or three-year leases, and this is a booming business. More and more people lease. And when the lease ends, their old vehicle is returned to the leasing company, which owns the vehicle, and which then sells it at auction, where a dealer buys it and then sells it as a used vehicle to a retail customer. These vehicles are only two or three years old, and often in mint condition.

Then there is the huge fleet or rental cars of about 2.2 million vehicles that are turned over every couple of years or so to enter the used-vehicle market, much of it via auctions held around the country.

In addition, there are corporate and government fleets that get turned over at different intervals, and those units end up on the used vehicle market.

So the rising average age doesn’t mean that Americans drive the same vehicle for a longer period of time – though they can, and many do – but that there is a strong market and demand for good older vehicles, and people buy them and drive them for a few more years.

But it is an issue for automakers. They could sell a lot more vehicles – and I mean a whole bunch more – if their vehicles on average reached the end of their life after eight years. But our finicky consumers don’t go for this program anymore. Quality is one of the factors that decides whether an automaker is going to make it or whether it will die.

What’s left for automakers to do to increase revenues in this environment of two decades of stagnating unit sales? A three-pronged industry strategy has emerged: Shift customers to more expensive vehicles, such as from cars to trucks and SUVs; load the vehicles with more goodies each year, such as driving-assist features; and jack up the prices pure and simple.

And automakers have been doing it across the board, which has the effect that for many Americans, new vehicles have become too expensive, and they stopped buying them, which puts further downward pressure on unit sales. But Wall Street, which keeps pushing automakers to go further and further upscale – because that’s where the money is – hasn’t figured this out yet.

https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2019-06-28/carmageddon-craves-cash-clunkers-20-average-vehicle-age-soars-record-high

June 28, 2019

With the nation’s economy on sound footing and incomes on the rise, the number of people forming households in the US has finally returned to a more normal pace. Housing production, however, has not. Our 2019 State of the Nation’s Housing report documents how the housing shortfall is keeping pressure on house prices and rents, eroding affordability for modest-income households in many markets. The 2019 report will be released in a live webcast today at 12:00 pm ET from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Several factors may be contributing to the slow construction recovery, including rising land prices, regulatory constraints, and persistent labor shortages. These constraints raise costs and limit the number of homes that can be built in places where demand is highest.

Despite these challenges, the report finds that the number of homeowners in the US continued to rise in 2018, while the number of renter households fell once again, a stark contrast to the increases of the 12 preceding years. Meanwhile, the share of households paying over 30 percent of their income for housing declined for the seventh straight year in 2017, but much of the progress was among homeowners, while cost burdens for modest-income renter households continued to rise.

To ensure the market can produce homes that meet the needs of a growing population, the public, private, and nonprofit sectors must address constraints on the development process. And for the millions who struggle to find housing that fits their budget, public efforts will be necessary to close the gap between what they can afford and the cost of producing decent housing.

Read the full report here:

https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/state-nations-housing-2019

June 28, 2019

With the nation’s economy on sound footing and incomes on the rise, the number of people forming households in the US has finally returned to a more normal pace. Housing production, however, has not. Our 2019 State of the Nation’s Housing report documents how the housing shortfall is keeping pressure on house prices and rents, eroding affordability for modest-income households in many markets. The 2019 report will be released in a live webcast today at 12:00 pm ET from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Several factors may be contributing to the slow construction recovery, including rising land prices, regulatory constraints, and persistent labor shortages. These constraints raise costs and limit the number of homes that can be built in places where demand is highest.

Despite these challenges, the report finds that the number of homeowners in the US continued to rise in 2018, while the number of renter households fell once again, a stark contrast to the increases of the 12 preceding years. Meanwhile, the share of households paying over 30 percent of their income for housing declined for the seventh straight year in 2017, but much of the progress was among homeowners, while cost burdens for modest-income renter households continued to rise.

To ensure the market can produce homes that meet the needs of a growing population, the public, private, and nonprofit sectors must address constraints on the development process. And for the millions who struggle to find housing that fits their budget, public efforts will be necessary to close the gap between what they can afford and the cost of producing decent housing.

Read the full report here:

https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/state-nations-housing-2019