The Urethane Blog

Everchem Updates

VOLUME XXI

September 14, 2023

Everchem’s exclusive Closers Only Club is reserved for only the highest caliber brass-baller salesmen in the chemical industry. Watch the hype video and be introduced to the top of the league: — read more

September 27, 2021

Millions Of Chinese Residents Lose Power After Widespread, “Unexpected” Blackouts; Power Company Warns This Is “New Normal”

by Tyler DurdenMonday, Sep 27, 2021 – 12:40 PM

Just yesterday we warned that a “Power Supply Shock Looms” as the energy crisis gripping Europe – and especially the UK – was set to hammer China, and just a few hours later we see this in practice as residents in three north-east Chinese provinces experienced unannounced power cuts as the electricity shortage which initially hit factories spreads to homes.

People living in Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces complained on social media about the lack of heating, and lifts and traffic lights not working.

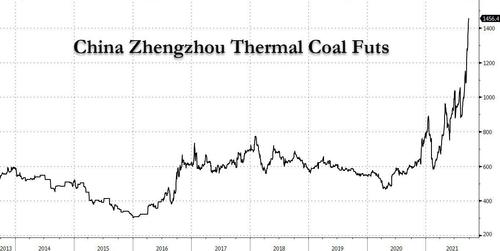

Local media in China – which is highly dependent on coal for power – said the cause was a surge in coal prices leading to short supply. As shown in the chart below, Chinese thermal coal futures have more than doubled in price in the past year.

There are several reasons for the surge in thermal coal, among them already extremely tight energy supply globally (that’s already seen chaos engulf markets in Europe); the sharp economic rebound from COVID lockdowns that has boosted demand from households and businesses; a warm summer which led to extreme air condition consumption across China; the escalating trade spat with Australia which had depressed the coal trade and Chinese power companies ramping up power purchases to ensure winter coal supply. Then there is Beijing’s pursuit of curbing carbon emissions – Xi Jinping wants to ensure blue skies at the Winter Olympics in Beijing next February, showing the international community that he’s serious about de-carbonizing the economy – that has led to artificial bottlenecks in the coal supply chain.

The coal price surge prompted the China Electricity Council to publish a statement saying that “to ensure winter coal supply, power companies continue to increase market purchases *regardless of cost* under the situation of substantial losses.”

Whatever the reason, it’s just getting started: as BBC reported, one power company said it expected the power cuts to last until spring next year, and that unexpected outages would become “the new normal.” Its post, however, was later deleted.

At first, the energy shortage affected factories and manufacturers across the country, many of whom have had to curb or stop production in recent weeks. In the city of Dongguan, a major manufacturing hub near Hong Kong, a shoe factory that employs 300 workers rented a generator last week for $10,000 a month to ensure that work could continue. Between the rental costs and the diesel fuel for powering it, electricity is now twice as expensive as when the factory was simply tapping the grid.

“This year is the worst year since we opened the factory nearly 20 years ago,” said Jack Tang, the factory’s general manager. Economists predicted that production interruptions at Chinese factories would make it harder for many stores in the West to restock empty shelves and could contribute to inflation in the coming months.

Three publicly traded Taiwanese electronics companies, including two suppliers to Apple and one to Tesla, issued statements on Sunday night warning that their factories were among those affected. Apple had no immediate comment, while Tesla did not respond to a request for comment.

But over the weekend residents in some cities saw their power cut intermittently as well, with the hashtag “North-east electricity cuts” and other related phrases trending on Twitter-like social media platform Weibo.

The extent of the blackouts is not yet clear, but nearly 100 million people live in the three provinces.

In Liaoning province, a factory where ventilators suddenly stopped working had to send 23 staff to hospital with carbon monoxide poisoning.

There were also reports of some who were taken to hospital after they used stoves in poorly-ventilated rooms for heating, and people living in high-rise buildings who had to climb up and down dozens of flights of stairs as their lifts were not functioning. Some municipal pumping stations have shut down, prompting one town to urge residents to store extra water for the next several months, though it later withdrew the advice.

One video circulating on Chinese media showed cars travelling on one side of a busy highway in Shenyang in complete darkness, as traffic lights and streetlights were switched off. City authorities told The Beijing News outlet that they were seeing a “massive” shortage of power.

Social media posts from the affected region said the situation was similar to living in neighboring North Korea.

The Jilin provincial government said efforts were being made to source more coal from Inner Mongolia to address the coal shortage.

As noted previously, power restrictions are already in place for factories in 10 other provinces, including manufacturing bases Shandong, Guangdong and Jiangsu.

Of course, a key culprit behind China’s shocking blackouts is Xi Jinping’s recent pledge that his country will reach peak carbon emissions within nine years. As a reminder, two-thirds of China’s electricity comes from burning coal, which Beijing is trying to curb to address climate change. While coal prices have surged along with demand, because the government keeps electricity prices low, particularly in residential areas, usage by homes and businesses has climbed regardless.

Faced with losing more money with each additional ton of coal they burn, some power plants have closed for maintenance in recent weeks, saying that this was needed for safety reasons. Many other power plants have been operating below full capacity, and have been leery of increasing generation when that would mean losing more money, said Lin Boqiang, dean of the China Institute for Energy Policy Studies at Xiamen University.

“If those guys produce more, it has a huge impact on electricity demand,” Professor Lin said, adding that China’s economic minders would order those three industrial users to ease back.

Meanwhile, even as it cracks down on conventional fossil fuels, China still does not have a credible alternative “green” source of energy. Adding insult to injury, various regions have been criticized by the government for failing to make energy reduction targets, putting pressure on local officials not to expand power consumption, the BBC’s Stephen McDonell reports.

And while the blackouts starting to hit household power usage are at most an inconvenience, if one which may soon result in even more civil unrest if these are not contained, a bigger worry is that the already snarled supply chains could get even more broken, leading to even greater supply-disruption driven inflation.

As Source Beijing reports, several chip packaging service providers of Intel and Qualcomm were told to shut down factories in Jiangsu province for several days amid what could be the worst power shortage in years.

The blackout is expected to affect global semiconductor supplies – which as everyone knows are already highly challenged – if the power cuts extend during winter.

The NYT confirms as much, writing today that the electricity shortage is starting to make supply chain problems worse. The sudden restart of the world economy has led to shortages of key components like computer chips and has helped provoke a mix-up in global shipping lines, putting in the wrong places too many containers and the ships that carry them.

Nationwide power shortages have prompted economists to reduce their estimates for China’s growth this year. Nomura, a Japanese financial institution, cut its forecast for economic expansion in the last three months of this year to 3 percent, from 4.4 percent.

It is not clear how long the power crunch will last. Experts in China predicted that officials would compensate by steering electricity away from energy-intensive heavy industries like steel, cement and aluminum, and said that might fix the problem. State Grid, the government-run power distributor, said in a statement on Monday that it would guarantee supplies “and resolutely maintain the bottom line of people’s livelihoods, development and safety.”

Maybe China should just blame bitcoin miners for the crisis to avoid public anger… alas, it can’t do that since it already banned them and drove most of its technological innovators out of the country.

September 27, 2021

Why are supply chains so messed up?

Craig Fuller, CEO at FreightWaves Follow on Twitter Saturday, September 25, 2021 4 minutes read

This is the question that I am asked on a daily basis. The issue is very complex, so I usually quip with a surprising response, “They’ve always had issues, but no one was really paying attention.” Turns out, unless the person works in freight, they are very unsatisfied with this answer. After all, freight and products just seemed to automatically show up before, but that is no longer the case.

Anyone that has been around supply chains knows that there have always been issues and challenges. Weather, economic cycles, capacity, pricing fluctuations, labor strikes, war, terrorism, policy changes, etc. -– have been with us since trade first began and those issues (and others) have always been a part of managing cargo flows. But 2021 is something much bigger entirely. Why is that?

The simple answer is there is a sudden and massive surge of demand that far outweighs the market’s capacity. The global supply chain infrastructure that exists simply can’t handle the volume of products flowing through the economy. The root cause can be blamed on the extraordinary government stimulus that has stimulated demand.

As the money flowed from the government, it ended up in the hands of consumers and businesses that spent it. The transfer of money coincided with a shift in consumer demand from purchasing services to purchasing physical products. This caused the United States to race through trillions of dollars of inventory while domestic and global production was shut down.

Simply stated, production was shut down while the U.S. economy went into demand overdrive. As production came back online, the manufacturing sector responded by fulfilling an unprecedented backlog of orders.

China ramped up manufacturing and products started to flow again. And the volumes were much bigger than before. Every container ship was put to work to move the cargo across the oceans. However, ports were built to handle a certain volume and each port has a finite number of cranes and space to store containers. When the ports became flooded with cargo, they simply didn’t have the capacity to handle it. A lack of labor, trucks, warehouse capacity, and rail infrastructure all started to create significant supply chain challenges in handling the surge of cargo.

Ships have been piling up off the coasts in ever-increasing numbers and this is taking that capacity offline as the ports try to handle it.

And this is not just an issue in the United States. This issue also exists in China. In fact, as I write this, the coastal cities of China have four times as many ships sitting off the coast as the Pacific ports in the United States do.

The oceans are also just one part of the story. To get freight to American consumers, it must go through an intricate system – shifting from port to other modes of transportation. This may include dozens of touchpoints in the domestic freight network, all of which are vulnerable to their own choke points.

Once a cargo shipment reaches the U.S. docks, it may go from truck to rail to truck to distribution center back to truck and dozens of sorting facilities in between before you receive it. Most of the capacity constraints in the domestic market have been labor-related, i.e. not enough workers at the distribution centers or drivers in the trucks. Trucking companies and warehouse operators have tried to respond by jacking up wages, but are finding that it isn’t solving their employment challenges.

Trucking has the most challenging labor picture of all; it simply is a job of last resort for many people. When construction, retail, food service, gig economy, and warehousing are all competing with the trucking industry for labor, it is often the trucking industry that loses.

After all, the lifestyle for an over-the-road driver is unique and difficult. Being forced to stay away from home for three weeks at a time is a major turn-off for many.

Truck driving is hard work and often the only recourse carriers have to attract more drivers is more money. But with alternative employment offering similar pay packages – but not requiring someone to stay away from home for weeks at a time, trucking companies are finding that new would-be drivers are not coming into the market in the numbers needed.

The challenges don’t end there. Warehouses and distribution centers have their own labor issues along with space constraints.

In the industrial sector, the supply chain issues that are causing chaos for retailers are also keeping domestic manufacturers from being able to complete the production of their finished products. The most obvious is in the automotive industry. This has an additional knock-on effect of restricting truck capacity. Even if labor supply wasn’t a major factor in the trucking industry, the carriers wouldn’t be able to get their hands on new trucks to handle the freight supply. Simply said, there aren’t enough trucks and trailers on the road to handle all of the demand.

Will the supply chain issues end soon? Very unlikely.

Even if we solve for current demand on the oceans, at the ports, in the distribution centers, and in the trucking industry, we haven’t begun to discuss what happens when the government ramps up additional domestic spending. While most supply chain professionals would agree that investing in infrastructure is the right thing to do, the worry is that it will continue to compound the imbalances between supply and demand across the supply chain.

As domestic manufacturing ramps up to handle the building of new roads, bridges, and other physical construction projects, this will put a massive onslaught of freight on the market. It will also pull labor out of the trucking industry, which will further exacerbate the driver shortage. Construction jobs will become more valuable, as contractors try to handle the surge of new projects. In turn, this will drive wages higher and increase economic growth.

For transportation providers, the good news is that it appears that we have a long way to go before the market catches up with demand. This could go on for a few years and break the typical three-year boom-and-bust cycle. For shippers and supply chain professionals that pay for capacity, while the work has never been more challenging, the rewards have also never been greater. Managing supply chains is no longer a back-office function, largely ignored and taken for granted. Going forward, business survival will require a highly functioning supply chain run by professionals with the experience and instincts to respond.

Embrace it.

September 27, 2021

Why are supply chains so messed up?

Craig Fuller, CEO at FreightWaves Follow on Twitter Saturday, September 25, 2021 4 minutes read

This is the question that I am asked on a daily basis. The issue is very complex, so I usually quip with a surprising response, “They’ve always had issues, but no one was really paying attention.” Turns out, unless the person works in freight, they are very unsatisfied with this answer. After all, freight and products just seemed to automatically show up before, but that is no longer the case.

Anyone that has been around supply chains knows that there have always been issues and challenges. Weather, economic cycles, capacity, pricing fluctuations, labor strikes, war, terrorism, policy changes, etc. -– have been with us since trade first began and those issues (and others) have always been a part of managing cargo flows. But 2021 is something much bigger entirely. Why is that?

The simple answer is there is a sudden and massive surge of demand that far outweighs the market’s capacity. The global supply chain infrastructure that exists simply can’t handle the volume of products flowing through the economy. The root cause can be blamed on the extraordinary government stimulus that has stimulated demand.

As the money flowed from the government, it ended up in the hands of consumers and businesses that spent it. The transfer of money coincided with a shift in consumer demand from purchasing services to purchasing physical products. This caused the United States to race through trillions of dollars of inventory while domestic and global production was shut down.

Simply stated, production was shut down while the U.S. economy went into demand overdrive. As production came back online, the manufacturing sector responded by fulfilling an unprecedented backlog of orders.

China ramped up manufacturing and products started to flow again. And the volumes were much bigger than before. Every container ship was put to work to move the cargo across the oceans. However, ports were built to handle a certain volume and each port has a finite number of cranes and space to store containers. When the ports became flooded with cargo, they simply didn’t have the capacity to handle it. A lack of labor, trucks, warehouse capacity, and rail infrastructure all started to create significant supply chain challenges in handling the surge of cargo.

Ships have been piling up off the coasts in ever-increasing numbers and this is taking that capacity offline as the ports try to handle it.

And this is not just an issue in the United States. This issue also exists in China. In fact, as I write this, the coastal cities of China have four times as many ships sitting off the coast as the Pacific ports in the United States do.

The oceans are also just one part of the story. To get freight to American consumers, it must go through an intricate system – shifting from port to other modes of transportation. This may include dozens of touchpoints in the domestic freight network, all of which are vulnerable to their own choke points.

Once a cargo shipment reaches the U.S. docks, it may go from truck to rail to truck to distribution center back to truck and dozens of sorting facilities in between before you receive it. Most of the capacity constraints in the domestic market have been labor-related, i.e. not enough workers at the distribution centers or drivers in the trucks. Trucking companies and warehouse operators have tried to respond by jacking up wages, but are finding that it isn’t solving their employment challenges.

Trucking has the most challenging labor picture of all; it simply is a job of last resort for many people. When construction, retail, food service, gig economy, and warehousing are all competing with the trucking industry for labor, it is often the trucking industry that loses.

After all, the lifestyle for an over-the-road driver is unique and difficult. Being forced to stay away from home for three weeks at a time is a major turn-off for many.

Truck driving is hard work and often the only recourse carriers have to attract more drivers is more money. But with alternative employment offering similar pay packages – but not requiring someone to stay away from home for weeks at a time, trucking companies are finding that new would-be drivers are not coming into the market in the numbers needed.

The challenges don’t end there. Warehouses and distribution centers have their own labor issues along with space constraints.

In the industrial sector, the supply chain issues that are causing chaos for retailers are also keeping domestic manufacturers from being able to complete the production of their finished products. The most obvious is in the automotive industry. This has an additional knock-on effect of restricting truck capacity. Even if labor supply wasn’t a major factor in the trucking industry, the carriers wouldn’t be able to get their hands on new trucks to handle the freight supply. Simply said, there aren’t enough trucks and trailers on the road to handle all of the demand.

Will the supply chain issues end soon? Very unlikely.

Even if we solve for current demand on the oceans, at the ports, in the distribution centers, and in the trucking industry, we haven’t begun to discuss what happens when the government ramps up additional domestic spending. While most supply chain professionals would agree that investing in infrastructure is the right thing to do, the worry is that it will continue to compound the imbalances between supply and demand across the supply chain.

As domestic manufacturing ramps up to handle the building of new roads, bridges, and other physical construction projects, this will put a massive onslaught of freight on the market. It will also pull labor out of the trucking industry, which will further exacerbate the driver shortage. Construction jobs will become more valuable, as contractors try to handle the surge of new projects. In turn, this will drive wages higher and increase economic growth.

For transportation providers, the good news is that it appears that we have a long way to go before the market catches up with demand. This could go on for a few years and break the typical three-year boom-and-bust cycle. For shippers and supply chain professionals that pay for capacity, while the work has never been more challenging, the rewards have also never been greater. Managing supply chains is no longer a back-office function, largely ignored and taken for granted. Going forward, business survival will require a highly functioning supply chain run by professionals with the experience and instincts to respond.

Embrace it.

September 27, 2021

Future US chem demand fueled by re-shoring, strained by supply

Author: Al Greenwood

2021/09/22

HOUSTON (ICIS)–The US chemical industry should continue growing in the next few years, with demand being fueled by manufacturing plants returning to the country, economist Kevin Swift said on Wednesday.

However, shortages in labour and raw materials could keep chemical demand from growing faster, since these are slowing down important end markets such as automobiles and housing, Swift said.

He spoke during a presentation at the Societe de Chimie Industrielle. Swift’s comments were among his first since retiring as the chief economist for the American Chemistry Council (ACC).

The supply constraints were the downside in what is otherwise an optimistic outlook for the economy.

The purchasing managers’ index (PMI) from the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) points to further growth, Swift said. Another leading indicator, which was developed by Swift, has slowed down, but it still indicates more growth.

Swift’s indicator generally takes about three months of decline for it to signal a turn in the business cycle. “It’s not signalling that yet,” he said.

The decline is showing the effects of the Delta variant of the coronavirus, which is slowing down the leisure, hospitality and travel sectors of the economy, he said. Manufacturing continues to perform fairly well.

The number of new homes that have started construction stand at about 1.5m units, the highest since the housing crisis from 2006-2008, Swift said.

That level of housing starts reflects the millennial generation entering their peak years for house buying, Swift said.

The number of houses that have received permits but have not started construction illustrates the shortages of building materials and labour, Swift said. Some homebuilders are finishing houses without refrigerators and appliances.

The housing market is a key consumer of plastics and chemicals, such as plastic pipe, insulation, paints and coatings, adhesives and synthetic fibres. The ACC estimates that each new home built represents $15,000 worth of chemicals and derivatives.

Automobiles, another important end market, are also contending with supply shortages, particularly for semiconductor chips.

Those shortages should cause US automobile sales to dip during the third quarter before rebounding to an annualised rate of 17m/year, Swift said. “That’s actually a very good level, and that supports a lot of chemistry.”

In addition, automobiles in the US are becoming larger, so that will increase the amount of plastic and other chemicals that each one will consume, he said. As electric vehicles (EVs) become more popular, that will increase demand for other types of chemicals.

One exception is catalysts, which automobile companies use in catalytic converters. Because EVs have no emissions, they do not need catalytic converters.

Swift expects every major chemical end market in the US will expand in 2021. He noted weakness in printing, which reflects fewer people reading physical copies of media.

In 2022, he expects weakness in apparel and textile-mill products, two other US industries that have been in long-term decline.

RESHORING

The disruptions to supply chains have accelerated a trend towards bringing manufacturing plants closer to demand centres, a phenomenon known as reshoring.

Companies began considering reshoring 10 years ago in the aftermath of the Fukushima earthquake in Japan.

The earthquake shut down plants that were the sole suppliers of critical electrical chemicals, Swift said. Fukushima was a wake-up call for companies to start developing more resilient supply chains.

The coronavirus pandemic proved to be a bigger shock to supply chains, and Swift expects more companies to reshore production to North America.

The trend should benefit demand for plastic additives and electronic chemicals.

CHEM INVENTORIES REMAIN LOW

Inventories of chemicals should remain low until 2022, Swift said.

US chemical producers have struggled to restock because of disruptions caused by the coronavirus, an active hurricane season in 2020, winter storm Uri and more hurricanes in 2021.

“We just can’t seem to win this year with the weather,” Swift said.

For the economy in general, Swift warned that it could take time for all the supply constraints to become resolved. “It might take two years in some cases.”

US CHEMS TO MAINTAIN COST ADVANTAGE

Swift expects the US chemical industry to maintain its cost advantage through at least 2024. During that time, Brent oil prices should remain at $60-80/bbl.

US chemical producers benefit from relatively high oil prices because they overwhelmingly rely on gas-based feedstock such as ethane. Meanwhile, much of the world relies on oil-based naphtha.

As a rule of thumb, the US chemical industry has a cost advantage when oil prices are at least 7 times higher than those for natural gas.

That ratio has remained above 7 even with the recent rally in US prices for natural gas, which broke $5/MMBtu for the first time in years.

CHEMICAL UTILISATION RATES TO RISE

Swift expects average utilisation rates for the chemical industry to rise in the upcoming years because companies have announced few new projects.

Chemical producers began announcing plans to build new US plants in the early 2010s in response to the advent of shale gas, Swift said. Those announcements peaked in 2014 and have since trailed off.

New plants take six to eight years to complete, he said. With that, the pace of new plant start-ups should slow in the second half of this decade.

If demand continues to rise, then utilisation rates should increase rise by quite a bit, Swift said.

High operating rates benefit chemical companies because it lowers their production costs for each tonne of product that they manufacture.

September 27, 2021

Future US chem demand fueled by re-shoring, strained by supply

Author: Al Greenwood

2021/09/22

HOUSTON (ICIS)–The US chemical industry should continue growing in the next few years, with demand being fueled by manufacturing plants returning to the country, economist Kevin Swift said on Wednesday.

However, shortages in labour and raw materials could keep chemical demand from growing faster, since these are slowing down important end markets such as automobiles and housing, Swift said.

He spoke during a presentation at the Societe de Chimie Industrielle. Swift’s comments were among his first since retiring as the chief economist for the American Chemistry Council (ACC).

The supply constraints were the downside in what is otherwise an optimistic outlook for the economy.

The purchasing managers’ index (PMI) from the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) points to further growth, Swift said. Another leading indicator, which was developed by Swift, has slowed down, but it still indicates more growth.

Swift’s indicator generally takes about three months of decline for it to signal a turn in the business cycle. “It’s not signalling that yet,” he said.

The decline is showing the effects of the Delta variant of the coronavirus, which is slowing down the leisure, hospitality and travel sectors of the economy, he said. Manufacturing continues to perform fairly well.

The number of new homes that have started construction stand at about 1.5m units, the highest since the housing crisis from 2006-2008, Swift said.

That level of housing starts reflects the millennial generation entering their peak years for house buying, Swift said.

The number of houses that have received permits but have not started construction illustrates the shortages of building materials and labour, Swift said. Some homebuilders are finishing houses without refrigerators and appliances.

The housing market is a key consumer of plastics and chemicals, such as plastic pipe, insulation, paints and coatings, adhesives and synthetic fibres. The ACC estimates that each new home built represents $15,000 worth of chemicals and derivatives.

Automobiles, another important end market, are also contending with supply shortages, particularly for semiconductor chips.

Those shortages should cause US automobile sales to dip during the third quarter before rebounding to an annualised rate of 17m/year, Swift said. “That’s actually a very good level, and that supports a lot of chemistry.”

In addition, automobiles in the US are becoming larger, so that will increase the amount of plastic and other chemicals that each one will consume, he said. As electric vehicles (EVs) become more popular, that will increase demand for other types of chemicals.

One exception is catalysts, which automobile companies use in catalytic converters. Because EVs have no emissions, they do not need catalytic converters.

Swift expects every major chemical end market in the US will expand in 2021. He noted weakness in printing, which reflects fewer people reading physical copies of media.

In 2022, he expects weakness in apparel and textile-mill products, two other US industries that have been in long-term decline.

RESHORING

The disruptions to supply chains have accelerated a trend towards bringing manufacturing plants closer to demand centres, a phenomenon known as reshoring.

Companies began considering reshoring 10 years ago in the aftermath of the Fukushima earthquake in Japan.

The earthquake shut down plants that were the sole suppliers of critical electrical chemicals, Swift said. Fukushima was a wake-up call for companies to start developing more resilient supply chains.

The coronavirus pandemic proved to be a bigger shock to supply chains, and Swift expects more companies to reshore production to North America.

The trend should benefit demand for plastic additives and electronic chemicals.

CHEM INVENTORIES REMAIN LOW

Inventories of chemicals should remain low until 2022, Swift said.

US chemical producers have struggled to restock because of disruptions caused by the coronavirus, an active hurricane season in 2020, winter storm Uri and more hurricanes in 2021.

“We just can’t seem to win this year with the weather,” Swift said.

For the economy in general, Swift warned that it could take time for all the supply constraints to become resolved. “It might take two years in some cases.”

US CHEMS TO MAINTAIN COST ADVANTAGE

Swift expects the US chemical industry to maintain its cost advantage through at least 2024. During that time, Brent oil prices should remain at $60-80/bbl.

US chemical producers benefit from relatively high oil prices because they overwhelmingly rely on gas-based feedstock such as ethane. Meanwhile, much of the world relies on oil-based naphtha.

As a rule of thumb, the US chemical industry has a cost advantage when oil prices are at least 7 times higher than those for natural gas.

That ratio has remained above 7 even with the recent rally in US prices for natural gas, which broke $5/MMBtu for the first time in years.

CHEMICAL UTILISATION RATES TO RISE

Swift expects average utilisation rates for the chemical industry to rise in the upcoming years because companies have announced few new projects.

Chemical producers began announcing plans to build new US plants in the early 2010s in response to the advent of shale gas, Swift said. Those announcements peaked in 2014 and have since trailed off.

New plants take six to eight years to complete, he said. With that, the pace of new plant start-ups should slow in the second half of this decade.

If demand continues to rise, then utilisation rates should increase rise by quite a bit, Swift said.

High operating rates benefit chemical companies because it lowers their production costs for each tonne of product that they manufacture.