History

August 22, 2021

History of the Pillow

The pillow was once viewed as a mystical implement with roles that extended far beyond providing a comfortable perch for our sleeping heads. (junrong/Shutterstock) Mind & Body

The Mystical Origins of the Pillow

For much of human history, pillows had much grander role than just cradling our sleeping heads By Tatiana Denning August 22, 2021 Updated: August 22, 2021 biggersmallerPrint

“We are such stuff as dreams are made on; and our little life is rounded with a sleep.” – William Shakespeare, “The Tempest”

A good night’s sleep is imperative to both our mental and physical well-being, and allows for the regeneration of both mind and body.

Sleep hygiene, including things such as a regular bedtime and proper sleeping environment, goes a long way toward a good night’s rest. A cool, dark, quiet room, a comfortable bed, and a supportive pillow can all help ensure you get adequate sleep.

While the pillow may seem to be a simple concept, and a common item we take for granted, it hasn’t always been the soft, fluffy nighttime companion we’re accustomed to today. In fact, what ancient societies used for a pillow would give most of us pause.

The First Pillow

The first pillow is believed to have originated in ancient Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq) around the year 7,000 B.C., making the pillow about 9,000 years old (not counting ancient civilizations we may have long forgotten).

This pillow was made of stone, and was used not for comfort or support, but rather for purely utilitarian purposes. It raised the head off the ground to help keep insects and other critters from climbing into a person’s hair, mouth, ears, and nose.

With time, ancient civilizations came to believe that the pillow could also provide support for the head. Stone was thought to be the best way to provide support, and so continued to be used for this reason. Stone was also immune to insects and bugs, unlike various softer materials. But carved stone was expensive, which meant that only the wealthy could afford to own a purpose-built pillow. As such, the pillow came to be viewed as a status symbol in ancient times.

Ancient China

More is probably known about the use of the pillow in ancient China than in any other culture.

The hard pillow maintained its popularity in ancient China. While the people of ancient China had the knowledge and ability to create a soft pillow, most looked down on it, believing a soft pillow robbed the body of its essential energy and vitality.

The ancient Chinese believed the proper pillow, as well as the proper furniture, could also rectify a person’s behavior and personality. While people today desire comfort, the ancient Chinese valued improving one’s moral character over a life of ease. This is one reason ancient Chinese pillows and furniture were made of hard materials.

The hard pillow was believed to have a variety of other benefits. It served to not only support the head and neck, but helped maintain the complex hairstyles of the time while sleeping, increase blood circulation, and improve one’s intellect. According to renowned auction house Christie’s, the ancient Chinese pillow also was used to keep one cool while sleeping, “Poet Zhang Lei of the Northern Song dynasty wrote: ‘Pillow made by Gong is strong and blue; an old friend gave it to me to beat the heat; it cools down the room like a breeze; keeping my head cool while I sleep’.”

A variety of materials were used to make pillows in ancient China, including porcelain, jade, pottery, bamboo, wood, and bronze. It was said that the material a person rested their head upon would influence their health, therefore, one should choose wisely.

Perhaps no material was more popular for pillow making in ancient China than ceramic. According to Christie’s, ceramic reached the height of its popularity during the Tang (618–907 A.D) and Song (960–1279 A.D) dynasties, before eventually being replaced by Western-style stuffed pillows. These pillows were often ornately shaped and decorated, and just like in Mesopotamia, were reserved for the wealthy and viewed as a symbol of status and prosperity. Butterflies, flowers, and children at play were just a few of the auspicious images commonly used on pillows, while inscriptions of Buddhist, Daoist, or Confucius teachings were often put on pillows to help improve one’s moral character.

The hard pillow was also said to ward off evil spirits, something the soft pillow couldn’t do. The lion, tiger, and Chinese dragon, in particular, were said to be effective at keeping evil spirits away.

“Lions were regarded as auspicious creatures with sufficient ferocity, strength, and spiritual energy to ward off evil spirits,” according to Christie’s. Many pillows were either made in the shape of these animals, or bore images of them.

While the hard pillow was viewed most favorably, there were pillows made of other materials for use in special circumstances. One such pillow was the medicinal pillow. According to Taiwan Today, this pillow was made of various herbs wrapped in silk cloth; it was used to improve hearing, keep the eyes sharp, return gray hair to its original color, regrow lost teeth, and cure a variety of diseases.

Due to its close proximity to the head, the pillow was also said to help promote and guide dreams. The ancient Chinese believed dreams had significant meaning, and they were taken as omens of what was to come.

“There was no sharp dichotomy in the division between the two states of spirit and matter in Chinese popular thought,” according to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. “Ghosts, spirits, and visions in dreams were part of the material world and deemed to be interchangeable with life. Thus the pillow could be a material object of great importance, which mediated between the conscious and unconscious, between reality and the illusionary.”

Today, these beautifully created ancient pillows are sought by collectors, fetching prices in the tens of thousands of dollars.

Ancient Egypt

While less is known about the pillow, or headrest, of ancient Egypt, we do know it served more than just a pragmatic purpose for the ancient Egyptians as well. Most of what is known comes from the discovery of headrests in ancient tombs.

The people of ancient Egypt considered the head to be the spiritual and life center, and as such, they viewed the head as the most sacred part of the body. The pillow served to both support and, perhaps more importantly, protect the head in both life and death.

Like in Mesopotamia, pillows were typically made of stone, but blocks of wood, ceramic, and ivory were sometimes used as well. They were more narrow than ancient Chinese pillows, which supported both the head and the neck, and typically offered support only to the head—thus the name “headrest.”

Religious and magical beliefs were woven throughout ancient Egyptian society, and pillows, as well as other objects, were decorated with images meant to serve as both protection and decoration. One commonly engraved image, according to Pennsylvania’s Glencairn Museum, was that of Bes, “a protective deity whose role involved the protection of the home, mothers and children, and sleeping people.”

It was believed that a sleeping person was particularly vulnerable to evil spirits, and the fearsome image of Bes provided protection from nighttime evils.

The ancient Egyptians placed tremendous importance on the afterlife, so much so that Tutankhamun, the boy king, was buried with eight headrests. Funerary texts contained hundreds of magical spells meant to help guide the dead safely into the afterlife.

“A handful of these spells make explicit reference to the headrest and compare it with the sun’s rising in the horizon. Coffin Text 232 reads: “A spell for the head-rest. May your head be raised, may your brow be made to live, may you speak for your own body, may you be a god, may you always be a god,” the Glencairn Museum states.

While beliefs may have changed, some parts of Africa still use these ancient-style headrests in their daily lives and find them quite enjoyable.

Ancient Greece and Rome

Even less is known about the pillows of ancient Greece and Rome.

What we do know is that the ancient Greeks and Romans eventually developed a penchant for luxury, comfort, and self-indulgence, abandoning the idea that the hard pillow had any physical or mental benefits. With their focus on comfort, they created the predecessor to today’s soft pillow.

The pillow used by everyday citizens of this time period was made of materials such as cotton, straw, or reeds, with pillows made of soft down and feathers being reserved for the wealthy. The pillow was viewed as a symbol of decadence, and people of this era are often pictured reclining on four or five luxurious pillows, even as they dined, often overindulging in food and wine.

According to Jason Linn in his UC–Santa Barbara dissertation on nighttime in ancient Rome, “Luxury pampered these people so greatly that even under dire circumstances they permitted their guards not only to sleep, but also to do so comfortably.”

The Spartans, however, held a different philosophy, and led austere lives without seeking comfort. Linn asks, “How could anyone sleep under such uncomfortable conditions?” The answer, “Doing so led to obedience, perseverance, and victories.” Linn goes on to quote William Arrowsmith, saying “luxury makes a man lose his specific function.”

As time marched on, reaching Europe’s Middle Ages, the soft pillow fell out of common use, and it was seen only as a status symbol. Men viewed the pillow as a sign of weakness, and at one point, only the king and pregnant women were allowed to lay their heads on a pillow at night.

By the 16th century, the pillow had come back into favor, but due to regular infestation by things such as mold, insects, and vermin, it was cumbersome to care for, with the contents of the pillow having to be changed regularly in order to maintain its cleanliness. Later on, pillows came to be used for kneeling in church, or as a place to rest holy texts. In some places, this is still done.

Modern Day

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, people’s way of life began to change across much of the world.

As technology continued to evolve, so did the story of the pillow. With the mass production capabilities of the Industrial Revolution, and the increase in the availability of cotton, the pillow was no longer only for the elite. The average person could now afford to own one, and the pillow gradually became common in every home.

As the Industrial Revolution brought material prosperity, society followed the pattern of the ancient Greeks and Romans: People sought out more comfort, ultimately ushering in a revolution of the soft pillow.

Today, pillows come in a variety of shapes, sizes, material types, and firmness levels. The types of pillows seem to be endless, with everything from gel, memory foam, down, feathers, down-alternative, cotton, innerspring, wool, latex, microbeads, kapok, buckwheat, and water available. That’s quite a list! Pillows can even be customized and personalized according to a person’s preference.

While the comforts of modern-day pillows may make our nights more comfortable, perhaps the ancients were onto something. I’m not inclined toward a return to a stone or ceramic pillow (though you can make your own version), but perhaps we should remember that sometimes a little discomfort in life isn’t such a bad thing.

From the perspective of the ancient Chinese, seeking comfort is rarely the best path. After all, when we endure a little hardship, we become more resilient. And amid life’s turmoils, if we can look within for the lesson, we’ll come out the better for having gone through it.

It seems even the pillow has a lesson to teach. Tatiana DenningD.O.

Tatiana DenningD.O.

https://www.theepochtimes.com/the-mystical-origins-of-the-pillow_3949673.html

June 14, 2021

Polyurethane Foam Association 40th Anniversary Video Series

June 14, 2021

ERA Polymers Celebrates 35 Years

Era Polymers: 35th anniversary

The Australian independent polyurethane systems house Era Polymers Pty Ltd with head office in Sydney announced that it is celebrating its 35th anniversary in 2021. According to the company, in 1986 George Papamanuel had the dream of owning his own polyurethane business. With the support of his wife Tina Papamanuel, hard work and determination, he realised that dream. George’s business started off small in his garage and he was always pinching Tina’s cooking utensils and crockery to test product.

Tina and George Papamanuel (Source: Era Polymers)

Tina and George Papamanuel (Source: Era Polymers)

Today, 35 years later, Era Polymers is one of the largest suppliers of prepolymers in Asia, operates six state-of-the-art manufacturing facilities (Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and United States) and exports to over 86 countries. However, the company is still very much a family affair with Alex, Francene, Nicole and Shannon all working in the business, said Era Polymers. The company’s polyurethane solutions comprise, amongst others, one of the most diverse ranges of cast elastomer prepolymers, spray polyurethane and polyurea’s, rigid and flexible foam systems, rubber binders and timber floor coatings.

Despite this growth and achievement George Papamanuel has always remained true to the business philosophy: “Business is people doing business with people”.While Era Polymers offers a global reach, the company said it remains important that its customers get great service locally.

https://www.gupta-verlag.com/news/industry/25291/era-polymers-35th-anniversary

April 14, 2021

Everything You Wanted to Know About Rhody’s, or is it Rhodies?

Rhododendron & Azalea News

Where Rhododendrons grow and how they got there.

by Steve Henning

Valley Forge Chapter ARS

| Earth’s Geologic Timeline | |

| Millions of Years Ago | The Event |

| 4,550 | Formation of the Earth |

| 4,527 | Formation of the Moon |

| circa. 4,000 | Heavy Meteor Showers End |

| circa. 3,700 | Earliest microbial life emerges |

| circa. 3,200 | Start of Photosynthesis |

| circa. 2,300 | Oxygen-rich Atmosphere |

| 760 | First creatures: Sea Sponges |

| 750-635 | Snowball Earth (ice covered) |

| 541-485 | Cambrian Explosion: All major animal phyla started appearing in fossil records. |

| circa 470 | Earliest Land Plants |

| circa 380 | First Vertebrate Land Animals |

| 270 | First Ginkgo biloba, a living fossil today |

| 230-66 | Non-Avian Dinosaurs Roamed The Earth |

| circa. 65 | Earliest Ericaceae |

| circa. 55 | Earliest Rhododendrons |

| circa. 25 | Beginning of Asian Monsoons |

| 2 | Earliest Hominins |

For the 1989 ARS Victoria convention, Ted Irving, a retired geophysicist and emeritus scientist with the Geological Survey of Canada, and Richard Hebda, a botanist with the Royal British Columbia Museum, presented an excellent program entitled Concerning The Origin and Distribution of Rhododendrons. It was subsequently published in JARS in 1993. This is a review of their landmark presentation with new material added.

Scientists have combined data from earth sciences, plant science and animal sciences to come up with a fairly detailed theory of when the earth was formed and how it developed.

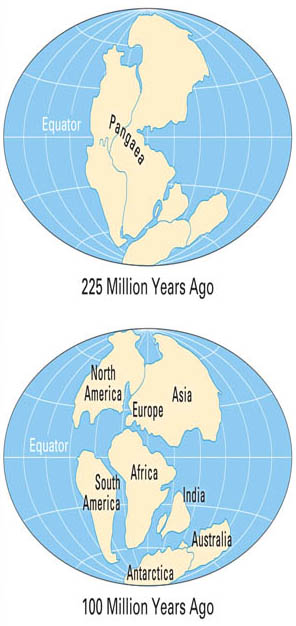

The theory of plate tectonics and continental drift explains many observations. The original continents Laurasia and Gondwana were together and formed the continent of Pangaea. When they drifted apart Laurasia contained what was to be North America and Eurasia, while Gondwana contained what was to be South America, Africa, India, Antarctica, and Australia. During these processes some areas sank and other areas rose from the oceans. But major land masses survived and the plants on them survived.

Fossil records indicate the Ericaceae emerged about 68 million years ago. Rhododendrons were found in fossils in North America and Eurasia.

Rhododendrons have been in existence for at least 55 million years, but not before 68 million years ago. This is significant because the regions of north Burma, southwest China, and New Guinea that we think of as the centers of rhododendron diversity did not exist 55 million years ago. Since fossils are usually found in lowlands, the lack of numerous fossil records of rhododendrons indicates they were more prevalent in upland habitats much as they are today. Fossil records of rhododendrons were present in North America and Eurasia dated soon after their origin. Alaska and Asia were connected by Beringia, a land mass, in what is now the Bering Strait.

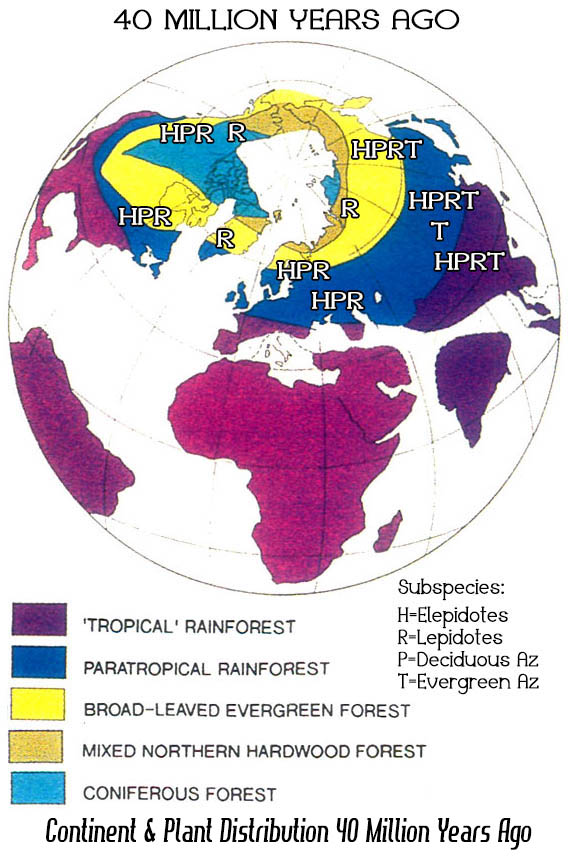

The following sections illustrate several stages in the paleogeographic evolution of rhododendrons proposed by Irving and Hebda. Except for the evergreen azaleas (Tsutsusi) which may always have been fairly restricted, rhododendrons were spread widely across the northern continents during the climatically-mild interval 60 to 40 million years ago. Although widespread and abundant, they were not necessarily represented by many species since they were not strongly diversified.

Plate tectonics and continental drift of plates.

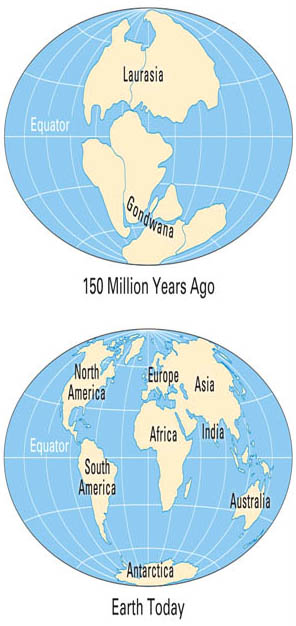

55 Million Years Ago

55 million years ago, the Beringia land bridge connected North America with Asia. The high mountains of south Asia hadn’t been formed because the India subcontinent was only approaching Asia. Also, at this time, South America was only approaching North America. Also significant is the fact that Mixed Northern Hardwood Forest connected the northern regions of North America and Asia even extending to Europe. Hence, whether rhododendrons originated in North America, Beringia, or Asia, they could freely spread both directions during the next 15 to 25 million years. Most of the world was tropical except the temperate polar region.

During the early history of rhododendrons 60 to 40 million years ago, North America and Eurasia were close to or north of the positions they occupy today; they were squarely lodged between 30 and 60°N latitude, with large areas north of 60°N. The climate, however, was warmer and more stable, and forests grew at much higher latitudes, because the Earth was then in a non-glacial stage. As a consequence, there apparently were only about four major vegetational zones, compared to about three times that number today. These were respectively, from south to north, “tropical” rain forest (“tropical” placed in quotes because such forest extended well outside the tropics), para-tropical rain forest, broad-leaved evergreen forest, and polar deciduous forest. These ancient forests can only be compared to modern forests in a general way because many modern forest trees had not yet evolved. For example, the dominant coniferous trees were not the spruces, pines and firs of today, but instead were, for the most part, members of the bald cypress family (Taxodiaceae), which includes such trees as the dawn redwoods, the redwoods and the bald cypress, whose range is fragmented now and restricted to small areas.

The polar deciduous forest, which included deciduous hardwoods and conifers such as the dawn redwood, occurred in northern North American and northern Siberia well inside the Arctic Circle. In and just south of the Arctic Circle there was a belt of broad-leaved evergreen forest which included palms, followed by a belt of warm para-tropical rain forest. Both belts probably extended into lower latitudes in upland areas, and both probably provided an environment suitable for rhododendrons. “Tropical” rain forests were the dominant vegetation, which, apparently, covered most low-lying regions in latitudes lower than about 45°. Most areas suitable for rhododendrons were likely to have occurred only in upland regions, but these could have been widespread.

It seems probable on geographic, climatic, and ecological grounds that rhododendrons, during their early history, could have extended more or less continuously from North America to Greenland and Europe, and eastward into China and northeastern Asia. It is probable that they moved freely between North America and Europe across the narrow gulfs of the emerging North Atlantic Ocean as well as across Beringia. The early populations of rhododendrons may not have been composed of very many species.

40 Million Years Ago

40 million years ago the temperate region was expanding southward. North America was developing its Coniferous Forest and Asia was developing a Broad-Leaved Evergreen Forest. There was still Beringia, the land connection between North America and Asia, and plants could easily migrate within the temperate region.

By 40 million years ago, there were about five global vegetational zones. “Tropical” rain forest occupied a smaller area than before. Polar deciduous forests persisted, and there was a notable development of a northern evergreen coniferous forest composed typically of members of the family Taxodiaceae. The belts of warm para-tropical rain forest and broad-leaved evergreen forest moved southwards and expanded. Except for high mountain regions of SE Asia and it high-island archipelago, both of which had not yet taken shape, the ranges of these two zones embrace the present-day distribution of rhododendrons, including that of the cold-climate R. lapponicum. It appears that in and between the places where rhododendrons are found nowadays, there existed habitats suitable for them. Rhododendrons are still more or less where they always have been.

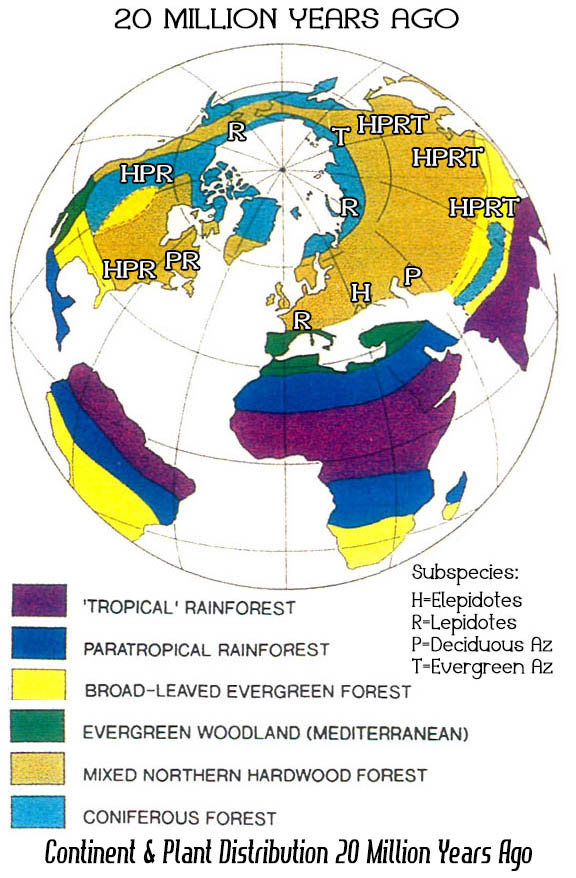

20 Million Years Ago

About 20 million years ago, the mild climate in middle and high latitudes began to deteriorate and as the North Atlantic opened, suitable environments were restricted and rhododendrons became confined to isolated pockets. At about this time, small founder populations of the subgenera Rhododendron (lepidote) and Hymenanthes (elepidote) colonized what is now high mountain regions of SE Asia as Tibet began to be uplifted, and the deep valleys on its southeastern border were eroded. These founder populations proceeded to speciate, especially during the past few million years.

We see that the temperate region extended throughout North America and Eurasia. There was still a land connection between North America and Asia and plants could easily migrate within the temperate region.

By 20 million years ago “tropical” rain forests were further restricted, and cooling in middle and high latitudes had begun. These changes culminated in the glacial periods of the past few million years. Variable continental climates and grasslands began to develop, and there was a further increase in the number of major vegetational zones from about six about 20 million years ago, to about eight today, twice the number present when rhododendrons began. In the north, extensive coniferous forest dominated by the pine family (Pinaceae), came into existence. Its present-day descendant is the boreal forest of northern North America and northern Eurasia. Mixed hardwood and coniferous forest for the first time occupied large areas of Eurasia and North America, but the great broad-leaved evergreen forests were much diminished, becoming restricted as they are today to southeastern China and the southeastern United States. The mixed hardwood and broad-leaved evergreen forests provided the habitats best suited to rhododendrons.

Between 20 million years ago and today, and especially in the last few million years, the climate in middle and high latitudes became much cooler than when rhododendrons first made their appearance. Large areas of desert, semi-desert and grassland developed in central and southwestern North America, across Africa and into Asia. This expansion of arid environments eliminated vast tracts of rhododendron habitat. During the past 2 to 3 million years, vegetational zones fluctuated greatly in response to glacial advances and retreats. This disrupted the climate of lands bordering glaciated areas. There was a broad circumpolar belt of tundra and ice, and “tropical” rain forests shrank to a remnant of their former extent.

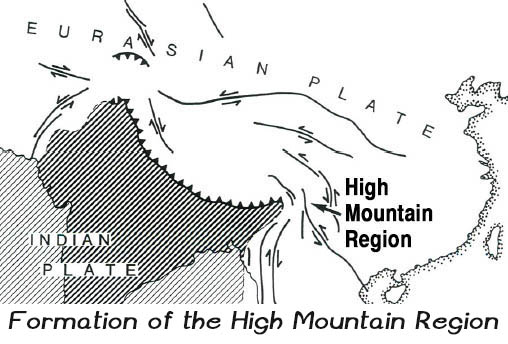

High Mountain Region

One of the most spectacular events in Earth’s history is the long drawn-out collision of India with Asia which began about 40 million years ago and continues today. This collision set in motion the chain of events which lead to the creation of the high mountain regions of SE Asia and to conditions highly favorable to the development of a rich rhododendron flora.

Prior to 120 million years ago, India formed part of the giant southern supercontinent, Gondwana, which fragmented in piecemeal fashion. In its northward travel. India relentlessly pushed northward, deforming much of southeastern Asia as it went. Immediately north of the zone of contact, the Earth’s crust was doubled in thickness and was lifted up forming the Tibetan Plateau. South of the plateau, debris piled up forming the Himalayas. Together the Tibetan Plateau and the Himalayas form a vast region of high elevation unique on Earth. It is the only region where two continents are colliding with one another today.

The most recent estimates are that the rapid uplift began about 20 million years ago, and that the plateau reached approximately its present elevation about 8 million years ago. The assembly of a landmass as large as Asia and the uplift of the Himalayas and Tibet profoundly affected climate.

Monsoons

About this time the monsoons began. They caused major changes in geography and climate. Monsoons started when India had collided with Asia creating the high mountain region in south Asia. Very low atmospheric pressure centered over Pakistan and stretching northeast to Mongolia developed in summer, drawing wet tropical air from across the equator, and causing heavy rainfall along the southeastern border of Tibet and the Himalayas. As uplift continued, river systems grew, their valleys were deeply etched along large faults in the Earth’s crust that had been developed as India pushed its way into Asia. It is this close fan-shaped network of faults along the southeast border of the Tibetan Plateau that accounts for the geometry and bunching together of the deep valleys. The fault-controlled alignment of valleys provides ready access to rain-bearing prevailing winds ensuring that the slopes of the high mountain regions of SE Asia are well watered. Through time, a landscape evolved which became home to a wide variety of habitats – sub-tropical valley bottoms, temperate slopes, and alpine peaks all very close together.

The monsoons altered the climate creating a rainy season and a dry season. The monsoons altered the geography by creating deep river gorges.

Founder Populations

Speciation occurs more readily in small reproductively isolated populations of plants and animals. In a small population, genetic drift is more likely to cause changes in a population’s characteristics. Such small reproductively isolated populations that undergo rapid diversification are referred to as “founder populations.”

As already explained, it is possible that during the period from about 60 to 40 million years ago, rhododendrons ranged more or less continuously across North America and Eurasia because suitable climates and topographies occurred there over a much wider area than at present. Although rhododendrons may have been widespread and abundant, the uniformity of conditions may not have led to the evolution of many species. As Asia was enlarged by the addition of India, and as the Tibet-Himalaya region was uplifted, new habitats ideal for rhododendrons came into being. Representatives of both lepidote (subgenus Rhododendron) and elepidote (subgenus Hymenanthes) rhododendrons, but not azaleas, expanded into these newly established favorable habitats and became founder populations. The mixed hardwood, coniferous and broad-leaved evergreen forests of eastern Asia 20 million years ago are their most likely habitat.

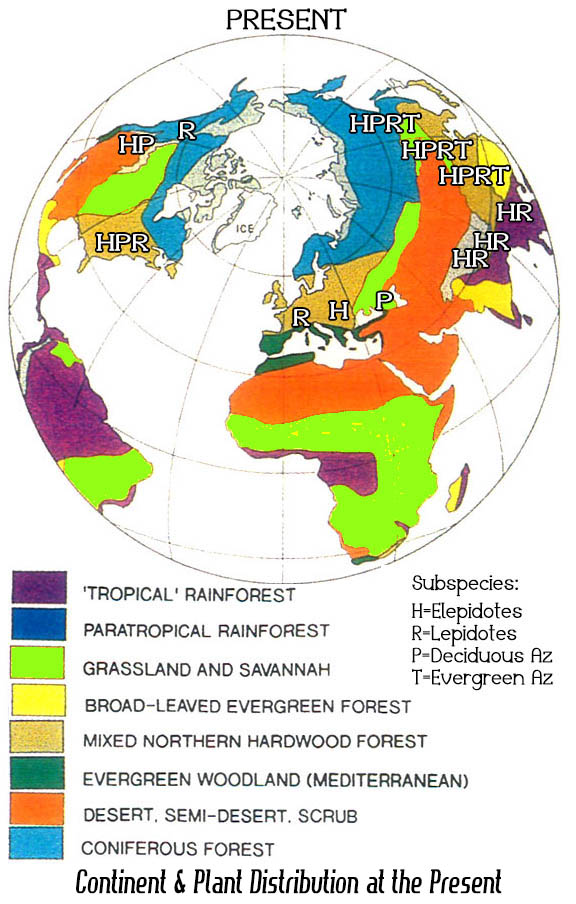

The Present

Fast-forward to the present and the connection between North America and Eurasia is gone. The temperate regions are larger and cold polar regions formed at both poles. The far northern climate is no longer hospitable to the more temperate rhododendrons. The region with temperate rhododendrons has now split with parts in western North America, eastern North America, Europe, and southern and Western Asia. The vireyas, an offshoot from the high mountain regions of SE Asia, were a late development which colonized the recently formed high-island archipelago.

Today there are broad belts of desert and semi-deserts in tropical and mid-latitudes which are bordered by broad expanses of tropical and temperate grasslands, something quite unknown 50 million or more years ago when rhododendrons first appeared. The region of broad-leaved evergreens and mixed hardwood and coniferous forest is confined to eastern and southeastern North America, Europe and Asia.

Global Climatic Change

Of course, it is not sufficient to say that because there is a suitably hilly landscape that rhododendrons would actually have grown there. A suitable climate is needed also, and the Earth’s climate is known to have changed drastically since rhododendrons first appeared.

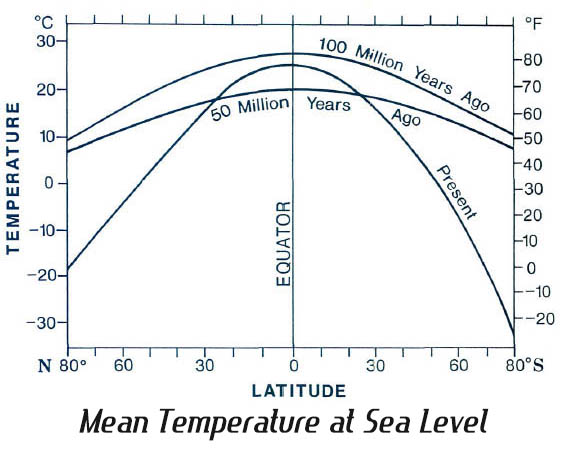

Today there is a year-round ice cap at both poles, the difference in mean surface temperature between pole and equator is over 40°C, and at latitudes above about 55° the mean surface temperature is below freezing. Earth is said to be in a “glacial period”. Earth has been in a glacial period for the past 2 to 3 million years, during which there have been large oscillations roughly every 50,000 years.

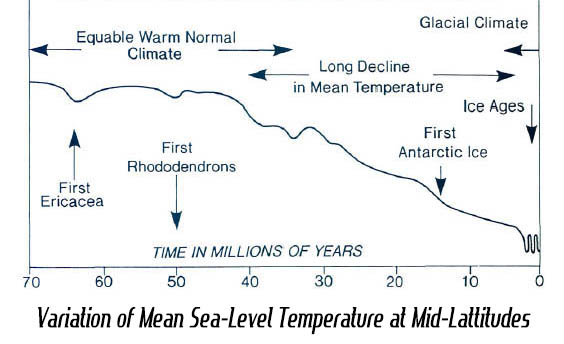

This much simplified graph shows the variation with time of mean surface temperature in middle latitudes. During the early history of ericaceous plants, the Earth had a stable non-glacial climate. This was followed by a long slow decline to about 3 million years ago when the present glacial period commenced, although there is evidence of glacial ice in Antarctica as long ago as 15 million years.

During ice ages glaciers have extended down into intermediate latitudes. Between ice ages, during interglacial periods, glaciers have diminished to about their present extent with glaciers at sea level only near the poles. For the past 10,000 years glaciers have been generally in recession. However, from 100 to 40 million years ago it was much warmer in high latitudes and the pole-to-equator temperature difference was only 10 or 15°C, one-third of that at present. There appears to have been no ice at sea level, and everywhere the mean surface temperature exceeded freezing (0°C). These are the characteristics of a “non-glacial period” and define Earth’s normal climatic regime. Today, climatically speaking, we live in exceptional times.

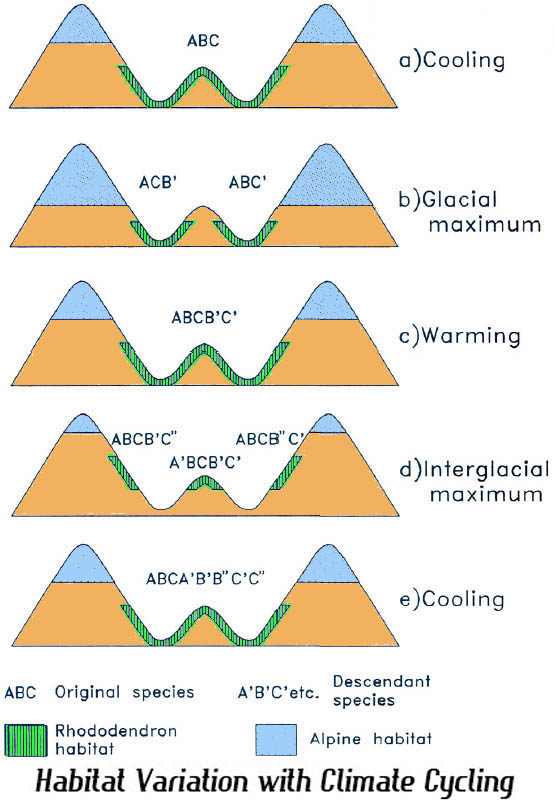

It is of vital significance for rhododendron evolution that the rapid uplift of the Tibetan Plateau was occurring at a time when global climate was cooling. As Earth entered a glacial period, ice advances and retreats occurred repeatedly every 50 to 100 thousand years.

Speciation in high mountain regions

In the high mountain regions of SE Asia, as an ice age commenced and harsh conditions at high altitudes expanded, species ranges would be displaced downward to lower elevations. Populations in valley bottoms, previously separated by unfavorable condition, could mix with populations from adjacent slopes and valleys, and species could cross after long intervals of separation to generate new hybrids, the potential progenitors of new species. Populations at higher elevations would become separated temporarily from one another by intervening glaciers or unfavorable alpine habitat. These now-separated populations would reproduce in isolation and, over time, diverge from each other by genetic drift following their own evolutionary path. During interglacial intervals, populations at higher elevation could migrate upward over ridges and opportunities for species to mix and separate repeatedly. The large vertical range of valleys and ranges meant that species distributions could be displaced rapidly upward and downward without annihilation, despite major climate shifts, because the actual distances travelled would be short. Consequently, fragmentation and coalescing of rhododendron habitats could have occurred repeatedly as a consequence of glaciation and deglaciation, so producing the present-day diverse flora.

In essence, mountains and deep valleys each act as islands of habitat which repeatedly join and separate as climatic zones and plant populations ascend and descend. These joining-separating cycles occur at about the right interval for them to serve as a forcing process for speciation. A period of 50 to 100 thousand years is generally considered sufficient for a small, physically isolated population to undergo changes great enough to ensure reproductive isolation. These separations and rejoinings would provide repeated opportunities for formerly isolated populations to intermingle.

The end result would be a very large number of closely related species many of which would retain the ability to hybridize. It was precisely this combination of very high mountains situated in tropical latitudes, and cycles of glaciation and deglaciation, that provided the dynamic conditions for the extraordinary speciation of lepidote and elepidote rhododendrons in the high mountain regions of SE Asia. According to this view, most of the speciation has happened in the last 3 million years during the current glacial period.

Lowland areas or mountains of modest size provide fewer opportunities for populations to separate and then rejoin (the hallmark of the above speciation mechanism). They provide no refuge in times of severe climate. In shallow valleys rhododendron populations would be eliminated or greatly reduced as climate deteriorated; as temperatures fell and valleys became occupied by unfavorable habitats or even filled with ice, there would be no possibility of downward migration; as rainfall diminished during warmer interglacial periods, there would be no nearby higher wetter slopes on which to find refuge.

Much of northern North America was covered by ice during major glaciations, whereas to the south relatively dry climate prevailed. There were few suitable habitats nearby, and during ice ages the local rhododendron population must have suffered severely. In the high mountain regions of SE Asia the correct balance appears to have been struck, so that although climatic changes were great, the tropical latitudes and the great depth of the valleys ensured that safe havens were nearby. In such a physical environment, latitudinally well-placed, climate change acts not as an agent of destruction, but as an incentive to diversification. Nowadays, because of its unique elevation, the high mountain regions of SE Asia is isolated botanically from the rest of the Asian land mass of which it is a part. Moreover, the region itself is a vast intricate honeycomb of valleys whose degree of isolation changes as ice ages wax and wane and as continuing uplift and erosion modify their configurations.

Azaleas

Azaleas differ from other rhododendrons in that azaleas only have about one tenth the number of species, and they are absent from the high mountain regions of SE Asia.

Deciduous azaleas occur mainly in southeastern USA and in southeastern Asia and Japan, with scattered representatives in southern Europe, Asia Minor, southwestern Asia, and western North America. This pattern indicates that, as has happened with the subgenera Hymenanthes and Rhododendron, they were more generally distributed over the northern hemisphere, and that their range has since been reduced and fragmented by climatic deterioration and widening of the North Atlantic, which increasingly presented a barrier to dispersal.

Evergreen azaleas are found only in southeastern China and Japan, and it is possible that they have always remained confined to warm temperate broad-leaved evergreen forests. They may never have ventured far beyond their original ecological niches, and their range has, in consequence, shrunk along with that of broad-leaved evergreen forests.

The azaleas are not plants of the high mountain regions of SE Asia although they live close by. Presumably, because of their genetic make-up and historical circumstances, they were unable to take advantage of the dynamic environment of the high mountain regions of SE Asia. Although well positioned to act as founder populations, they failed to do so. In this respect, the paleogeo-graphical evolution of azaleas appears therefore to have been very different from that of other rhododendrons.

Vireyas

The Indo-Malaysian region has an abundance of species from section Vireya of the subgenus Rhododendron. Other representatives of the genus are rare (the evergreen azalea R. subsessile grows in the Philippine Islands). Vireyas are also found, but in much fewer numbers, in the high mountain regions of SE Asia, in the mountain ranges of Indochina and Malaya, and in adjacent areas of southeastern China and Taiwan. In contrast to many other sections, such as the section Ponticum (of the sub-genus Hymenanthes) which has representatives in North America, Europe, and southeastern Asia and a markedly discontinuous distribution, the vireyas are concentrated in one essentially continuous region. This suggests that they have originated comparatively recently, more recently, for example, than the section Ponticum. The terrains in which the majority of vireyas are found today are of recent origin indicating that the abundance and diversity of vireyas is also a recent phenomenon. Many of the mountain ranges of the high-island archipelago, have been created by volcanic activity as the Indian and Pacific Plates pushed the Eurasian Plate up. The highlands of New Guinea, which exceed 4000 meters in relief, began to be uplifted about 4 million years ago. Because the region is near the equator, vegetational zones vary from tropical forest at sea level to alpine grassland with glaciers on the peaks, and they may have fallen as much as 1000 meters during ice ages. Hence, a mechanism for speciation similar to that proposed for the high mountain regions of SE Asia may also be operative here. The founder populations of the section Vireya most likely originated in the high mountain regions of SE Asia within the past few million years. From there they have spread swiftly down the Malay Peninsula into the high-island archipelago where they speciated rapidly. One species has even reached Australia, where it occurs in the tropical rain forest of the Atherton Tableland.

Summary

Rhododendrons originated over 55 million years ago and were more-or-less continuously distributed across North America and Eurasia. The climate was mild and change was slow. Their range became much reduced as a result of worsening of the global climate caused by the formation of high mountains. This worsening began about 25 million years ago, was clearly marked by about 15 million years ago, and became extreme with the onset of the current glacial period about 3 million years ago. Small founder populations of the sub-genera Hymenanthes and Rhododendron (but not azaleas) situated marginal to their main range were able to enter and retain a foothold in the newly developing high mountain regions on the southeastern fringe of the Tibet-Himalayan region. It was from there that the vireyas spread into the mountains of the high-island archipelago. By taking advantage of special newly developing conditions, these small, originally peripheral populations have become now the most numerous and diverse. The place of origin of rhododendrons is not known, but it was not the high mountain regions of SE Asia where nowadays they are most diverse and abundant. That region did not exist then. These conclusions are based on the fossil record of rhododendrons and are based upon the observations of many scientists. They provide reasonable explanations of the present remarkable distribution of rhododendrons and of their differing abilities to cross and recross.

References

- Sleumer, H., Flora Malesiana, series 1, Spermatophyta, Ericacaene, 6,469-914, 1972.

- Molnar, P. and Taponnier, P., Cenozoic Science, 189, 419-426, 1975.

- Savin, S.M., Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci., 5, 319-355, 1977.

- Cullen, J., Notes from the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, 39, 1-207, 1980.

- Chamberlain, D.F., Notes from the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, 39, 209-486, 1982.

- Mayr, E., The Growth of Biological Thought. Harvard U. Press, Cambridge, Mass, 1982.

- Wolfe, J.A., Amer. Geophys. Union Geophys. Monogr., 32, 357-375, 1985.

- Hope, G., In Barlow, B.A. (editor) Flora and Fauna of Alpine Australia, Ages and Origins, CSIRO, Melbourne, 131-145, 1986.

- Barron, E.J., Paleoceanography, 2, 729-739, 1987.

- Hill, K.C. and Gleadow, A.O.W., Australian. J. Earth Sci., 36, 515-539, 1989.

- Kron, K.A. and Judd, W.S., Systematic Botany, 15, 57-68, 1990.

- Harrison, T.M., Copeland, P., Kidd, W.S.F. and Yin, A., Science, 255, 1663-1670, 1992.

- Irving, E. and R. Hebda. JARS 47:39, 1993.

- Hall, D.H., JARS 52:1, 1998.

- An ZS, Kutzbach JE and Prell WL et al. Nature 2001; 411: 62–6.

- Denk, T., et.al., J. Linnean Society 149:369-417, 2005.

- KRON, KA. & LUTEYN, J.L. Biol. Skr. 55: 479-500, 2005.

- Quan C, Liu ZH and Utescher T et al. Earth-Sci Rev 2014; 139: 213–30.

- Lu YH and Guo ZT. Sci China Earth Sci; 57: 70–9, 2014.

- Renner SS. J Biogeogr; 43: 1479–87, 2016.

- Spicer RA. Plant Diversity; 39: 233–44, 2017.

- Shrestha N, Su X, Xu X, Wang Z. J Biogeogr. 45:438–447, 2018.

- Chen, Y-S., Natl Sci Rev, 5: 6, 2018.

American Rhododendron Society

P.O. Box 214, Great River, NY 11739

Ph: 631-533-0375 Fax: 866-883-8019 E-Mail: member@arsoffice.org

©1998-2020, ARS, All rights reserved.

http://rhodyman.net/History.html

March 27, 2021

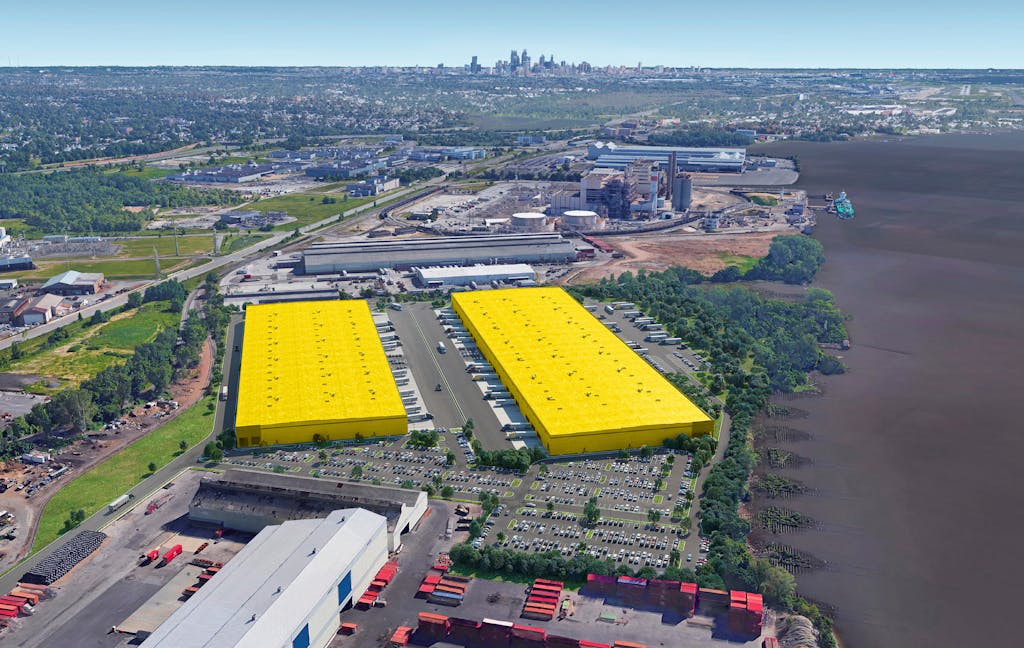

Former Foamex Eddystone, PA Site

For you nostalgia fans . . .

From what we found out, a company purchased the site for $15 MM USD last year (Foamex/FXI initially sold it to a metal recycling company for $13 MM in 2010). This new entity has plans to build on the site. The demolishment is ongoing. Reinhart did a little more research. The enclosed pdf file is what, at this point in time, appears to be the proposed future plans regarding this former foam plant. The big question about this “Eddystone” development is, we do not believe there is another road in/out of that place other than the front gate. This goes right by Penn Terminals then up to Rte 291. The Railroad tracks run parallel with Rte 291 all the way up past the airport and there is no other way under the tracks to the best of our knowledge. With all the potential new truck traffic, that one way out/in could become a bottleneck.

This is what the sight looks like as of last Friday:

Plant 1 Picture: Back and to the left is where the guard house/front gate used to be. The front, left corner of the plant building was directly in front of me. The silos in the far distance are at the end of the building.

Plant 2 Picture: I am in a similar position as above but looking towards the right. The far outside rear edge of the plant building is in the distance with the river and New Jersey past that.

R&D Bldg 2: Basically I am a similar position as above but looking to the left. The R&D building, which was across the street, is completely gone.

There is nothing left I could recognize except for the remains of the rail siding tracks. Difficult to believe that at one time this sight had: 3 foam pouring machines, multiple foam felting operations, Baumer loops, multiple foam reticulation operations, foam peeling operations, flame lamination operations, multiple pilot scale foam machines, full QC lab & operations, engineering, 27 person R&D group, etc.

Courtesy of Glenn DePhillipo RS & M Technologies