Current Affairs

October 9, 2021

Peak Problems

Hapag-Lloyd CEO: ‘We are probably in the peak of the problems’

Rolf Habben Jansen says ‘most of the difficulties’ — port congestion, capacity shortages and slow container turns — remain in US

Kim Link-Wills, Senior EditorThursday, October 7, 2021 11 minutes read

Congested ports. Clogged supply chains. Capacity shortages.

Much of Hapag-Lloyd CEO Rolf Habben Jansen’s third-quarter overview had a familiar refrain, one likely to be heard again after the fourth quarter.

But there were two topics Habben Jansen did not expound upon: the buckets of money the ocean carrier likely raked in during the third quarter and the recent investment in a German port.

Hapag-Lloyd is scheduled to release its third-quarter figures Nov. 12, and Habben Jansen did not open the ledger during a virtual chat with the media last week. His only reference to Q3 financials came when addressing supply chain bottlenecks.

“Once the data come out for the third quarter of 2021, I do not think that we will see massive growth compared to [Q2 year-over-year] simply because the supply chains at the moment are so much clogged up and we have so many ships waiting outside of the ports,” he said.

Hapag-Lloyd did experience massive second-quarter growth year-over-year. Q2 earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization was $2.3 billion, an eye-popping $1.5 billion gain from the $770 million reported in the second quarter of 2020. Revenue shot up 70%, from $3.3 billion in Q2 2020 to $5.6 billion this year.

Habben Jansen did touch on the ocean carrier’s stellar financial performance in the first half of 2021.

“On the back of higher transportation volumes and rates, we’ve seen a significant increase in results for the first half of the year. Contract rates are up, but of course very significantly below what we have seen in the spot market. We’re still loading, though, quite a few boxes at 2020 rate levels, especially medium- and long-term contracts,” he said.

“If you look at our overall numbers, then you will see that our average freight rate in the first half [of the] year was up compared to last year by about $500 per TEU. Of course, that’s quite a lot of money, but $500 a TEU is nowhere near the increases that we have seen in the spot market,” Habben Jansen continued. “That clearly illustrates that we’ve been moving a lot of cargo on contracts that were closed earlier.”

Hapag-Lloyd reported first-half 2021 EBITDA of $4.2 billion, a giant leap from $1.2 billion in 2020, and group profit of $3.3 billion, up from $2.9 billion the year before.

“Revenues increased in the first-half year of 2021 by approximately 51%, to $10.6 billion, mainly because of a 46% higher average freight rate of $1,1612/TEU. The freight rate development was the result of high demand combined with scarce transport capacities and severe infrastructural bottlenecks,” Hapag-Lloyd said in the August release.

“While demand remains high in the current congested market environment, it is leading to a shortage of available weekly transportation capacity. For this reason, Hapag-Lloyd expects earnings to remain strong in the second half of the financial year,” it said.

Full-year EBITDA is forecast in the range of $9.2 billion to $11.2 billion.

‘It’s very important to have a robust network’

Habben Jansen was asked several times to elaborate on Hapag-Lloyd’s investment in JadeWeserPort. Late last month, Hapag-Lloyd issued a brief statement in which it said it was acquiring a 30% stake in Container Terminal Wilhelmshaven and 50% of the shares of Rail Terminal Wilhelmshaven at JadeWeserPort in Germany for an undisclosed price.

More than once Habben Jansen was asked about the price, and more than once he said the parties involved had agreed not to disclose that information.

“I think we have given a number of arguments on why we believe that investing in Wilhelmshaven makes sense, I think the main argument being that we think that it will strengthen the position of the German ports … and hopefully over time will lead to more cargo coming in to the German ports,” he said.

Habben Jansen also declined to name other port investments Hapag-Lloyd may be eyeing.

“We won’t comment on specific locations, but the logic behind this is I think we have also learned over the last year and a half that it’s very important to have a robust network and that means you should concentrate, especially in transshipment, in a limited number of places. In those places, it’s then important to have control over terminal capacity,” he said, adding that Hapag-Lloyd “will probably consolidate all of our transshipment volume in … 12 or 15 locations around the globe, and it would not be illogical if we do investments in, say, half of those locations or so.”

‘The already congested supply chain is getting congested even further’

Habben Jansen did talk about the continuing high demand for ocean shipping.

“We’ve certainly seen strong demand on the back of the economic upturn and in the course of the first half. As far as we can see right now, we do expect that to continue. We still see today that demand is very strong on most trades, even if it’s definitely driven still very much by the U.S., because that’s where we see the strongest increases, on the trans-Pacific. And if we look at the last couple of months, also the Atlantic has been very strong,” Habben Jansen said.

“The difficulty that we of course all face at this point in time — and that’s not a secret — this strong demand, combined with a whole bunch of COVID-related restrictions and unexpected surge in volume, has led to quite a lot of difficulties in the supply chain.”

Those difficulties include the lack of available containers.

“The worst numbers we have seen so far were in the month of August, where the time that it takes us to get a container back is up about 20%, which also means that we need 20% more containers than we normally need to transport the same amount of volume.

“The same goes for voyage delays,” Habben Jansen said. “We also have seen these delays go up, and if we look at the situation today, we are probably in the peak of the problems. … The already congested supply chain is getting congested even further.”

The Ever Given blockage of the Suez Canal, COVID-caused port shutdowns in China and an earlier-than-usual peak season all have “put a lot of pressure on global supply chains and capacity. In many ports at the moment, capacity remains strained. This is the case in Asia, where we have significant delays when we look at Korea, we have significant delays when we look at China, also Singapore [is] not as smooth as it normally runs. If you go to Europe, especially in the north, [there are] definitely a number of ports where we have very significant waiting times,” he said.

“If we look at the United States, that’s probably where we still have most of the difficulties, not only in LA/Long Beach but also in other ports on the West Coast, but also increasingly at ports on the East Coast, where places like Savannah and New York are heavily congested.”

Habben Jansen said, “On average it takes us today 10 to 15 days longer before we get the box back. That in reality also means that there are quite a few TEUs globally that are currently somewhere in the supply chain that actually should already be at the warehouses of many of the customers.”

He reiterated that port congestion is not limited to the United States. “On a global basis, we see that pretty much every ship in the Hapag-Lloyd network needs to wait longer before it gets into any port. Those are significant effects.”

The supply chain problems extend beyond ports, Habben Jansen noted. “Let’s not forget that these difficulties are in many cases not limited to the ports only, but we also have bottlenecks on inland transportation. The most obvious bottlenecks, they’re definitely in the U.S., but also in places like the U.K., and in some places in Europe we also see that shortage of available inland capacity [is] prominent.”

He said Hapag-Lloyd has “implemented quite a lot of countermeasures to try and limit the impact on our customers and also to improve service quality.”

“We tried to move capacity to those places where it is needed the most. We’ve also tried to reroute cargo to alternative gateways because sometimes it is better to go to another port if you can berth there upon arrival rather than wait outside for a couple of days. We bought secondhand tonnage, we chartered extra ships, we deployed extra loaders. And we have ordered, in particular, a large number of additional containers,” Habben Jansen said.

This past spring Hapag-Lloyd ordered standard and refrigerated boxes to carry 210,000 twenty-foot equivalent units to combat “severe imbalances” caused by the shortage of containers around the world.

“We have been out to outinvest that problem, if you want. We have added several [hundred] thousand TEUs to our fleet, and I would say that today … that situation around the boxes is pretty much back to normal,” Habben Jansen said.

“In addition to that, we’ve also added people. We’ve added IT capacity. We’ve also developed a number of new digital services that have been launched over the last couple of months [to] allow customers to have better visibility where they actually can and cannot book, and it also allows us to get quicker feedback to our customers on things that are possible and not possible,” he said.

Spot rates and surcharges

Hapag-Lloyd is among the ocean carriers that have agreed “given where the market is today, we should not, even if capacity is very tight and supply and demand would allow us to do that, not raise spot rates any further, which we will abide by until further notice. The same goes for new surcharges,” Habben Jansen said.

Surcharges will come back into play, “but that will not be done today or tomorrow,” he said, advocating a change in the way fees are levied.

“They should be related to enforcing better behavior. If you have a very high no-show ratio, you should probably pay something like a cancellation fee. We at some point need to go and do our utmost to simplify those things,” Habben Jansen said. “Or if you always deliver us higher weight than you declare, then I think it’s fair that you have to pay extra for that. So I think our charges need to go more in the way we drive the right behavior between us.”

He believes there should be a clear understanding of what is expected from both carrier and shipper.

“For an example, if we ask people to bring their containers into the terminal 24 or 48 hours before departure of the ship, if the documentation is not complete before that time, then we will not load that cargo anymore. This all fits into becoming more professional between carrier and shipper. That’s probably, if we look back two or three years from today, that’s probably a good thing that this crisis will have brought,” Habben Jansen said.

Big ships and sustainability

Habben Jansen said “better results” have enabled Hapag-Lloyd to modernize its fleet.

“We have placed a number of orders to renew our fleet and also that’s where Hapag-Lloyd is not an exception. The global orderbook is currently I think a little bit north of 20%. It will take some time, though, before all those ships are going to be delivered,” he said.

Hapag-Lloyd has ordered 12 ships, each with a capacity of more than 23,500 TEUs, at a total cost of $852 million.

“Apart from investing in our fleet, we have also invested in other key areas of our business,” he said. “We’ve done quite a lot of things to boost our digital capabilities with the idea that we do try to provide better transparency on vessel departures and arrivals. We’ve opened up a number of new offices in places like Ukraine, Kenya, Senegal, Morocco, [with] a few more in the pipeline. And of course we’ve also closed on the acquisition of [African carrier] NileDutch.”

Habben Jansen said Hapag-Lloyd remains committed to reducing its carbon dioxide emissions by 60%, compared to 2008, by 2030.

“We have to invest in new ships, phase out older ones, try to see what we can do to use alternative fuels, whether that’s biofuel or synthetic fuel or liquid gas or other things. And yes, we want to achieve becoming carbon-neutral or net-zero carbon-neutral, but that will take time. The key thing here will be to get access to alternative fuels,” he said.

“The reality is, though, that the scaling of the production of those vessels will not be all that easy and that will take time. That’s also why we need to continue to invest in R&D, ideally industrywide. For now, we are making a shift to liquid gas as we believe that currently will be quite a good transitional solution, but more importantly, those ships can also, when you look at their machines and their engines, they will allow us to switch to other greener alternatives, and that could be various fuels,” Habben Jansen said.

He was asked if Hapag-Lloyd had a negative outlook on liquefied natural gas as a long-term fuel.

“For the time being, we do not intend to convert more [ships to LNG] because that conversion turned out to be significantly more expensive than we originally had hoped. It doesn’t mean that if we find another way to do it, we might still consider it, but for the time being, there’s nothing specifically planned there. In terms of the outlook of LNG, I mean, that has certainly changed over the last couple of quarters. There’s all kinds of reports coming out on that,” Habben Jansen said.

“There was a lot of support for LNG as a transition fuel. And I’d also emphasize that the engines we have in those ships cannot only use LNG but also a number of other liquid fuels, even if some of them we might need to do a little bit of modification,” he continued. “How long LNG will be around, I personally think it’s going to be around for quite a lot longer than many people think, simply because the scaling of production of alternative fuel is going to take quite a lot of time.”

Hapag-Lloyd had said in June that it was focusing on LNG “as a medium-term solution as it reduces CO2 emissions by around 15 to 25% and emissions of sulfur dioxide and particulate matter by more than 90%. Fossil LNG is currently the most promising fuel on the path toward zero emissions.”

Lessons learned

Habben Jansen said the supply chain crisis has taught a number of lessons.

“First of all, trying to stay close to the customer is very important. Also I think we’ve learned that trying to be as transparent as possible is important. Be as digital as you can because that allows people to do more and more things themselves. Make sure that we remain agile and flexible,” he said.

He also gave a tip of the hat to the long-suffering seafarers, “the backbone of global shipping,” and said that the crew change crisis brought to the forefront at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic remains a “very, very tough” situation.

“If we look at the operational challenges that we have, they are currently still very, very significant, and we do not expect to see any normalization until Chinese New Year ’22,” he said. “I would seriously hope that after that, we will see a gradual normalization — until we go into the next peak season of 2022.”

October 9, 2021

Peak Problems

Hapag-Lloyd CEO: ‘We are probably in the peak of the problems’

Rolf Habben Jansen says ‘most of the difficulties’ — port congestion, capacity shortages and slow container turns — remain in US

Kim Link-Wills, Senior EditorThursday, October 7, 2021 11 minutes read

Congested ports. Clogged supply chains. Capacity shortages.

Much of Hapag-Lloyd CEO Rolf Habben Jansen’s third-quarter overview had a familiar refrain, one likely to be heard again after the fourth quarter.

But there were two topics Habben Jansen did not expound upon: the buckets of money the ocean carrier likely raked in during the third quarter and the recent investment in a German port.

Hapag-Lloyd is scheduled to release its third-quarter figures Nov. 12, and Habben Jansen did not open the ledger during a virtual chat with the media last week. His only reference to Q3 financials came when addressing supply chain bottlenecks.

“Once the data come out for the third quarter of 2021, I do not think that we will see massive growth compared to [Q2 year-over-year] simply because the supply chains at the moment are so much clogged up and we have so many ships waiting outside of the ports,” he said.

Hapag-Lloyd did experience massive second-quarter growth year-over-year. Q2 earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization was $2.3 billion, an eye-popping $1.5 billion gain from the $770 million reported in the second quarter of 2020. Revenue shot up 70%, from $3.3 billion in Q2 2020 to $5.6 billion this year.

Habben Jansen did touch on the ocean carrier’s stellar financial performance in the first half of 2021.

“On the back of higher transportation volumes and rates, we’ve seen a significant increase in results for the first half of the year. Contract rates are up, but of course very significantly below what we have seen in the spot market. We’re still loading, though, quite a few boxes at 2020 rate levels, especially medium- and long-term contracts,” he said.

“If you look at our overall numbers, then you will see that our average freight rate in the first half [of the] year was up compared to last year by about $500 per TEU. Of course, that’s quite a lot of money, but $500 a TEU is nowhere near the increases that we have seen in the spot market,” Habben Jansen continued. “That clearly illustrates that we’ve been moving a lot of cargo on contracts that were closed earlier.”

Hapag-Lloyd reported first-half 2021 EBITDA of $4.2 billion, a giant leap from $1.2 billion in 2020, and group profit of $3.3 billion, up from $2.9 billion the year before.

“Revenues increased in the first-half year of 2021 by approximately 51%, to $10.6 billion, mainly because of a 46% higher average freight rate of $1,1612/TEU. The freight rate development was the result of high demand combined with scarce transport capacities and severe infrastructural bottlenecks,” Hapag-Lloyd said in the August release.

“While demand remains high in the current congested market environment, it is leading to a shortage of available weekly transportation capacity. For this reason, Hapag-Lloyd expects earnings to remain strong in the second half of the financial year,” it said.

Full-year EBITDA is forecast in the range of $9.2 billion to $11.2 billion.

‘It’s very important to have a robust network’

Habben Jansen was asked several times to elaborate on Hapag-Lloyd’s investment in JadeWeserPort. Late last month, Hapag-Lloyd issued a brief statement in which it said it was acquiring a 30% stake in Container Terminal Wilhelmshaven and 50% of the shares of Rail Terminal Wilhelmshaven at JadeWeserPort in Germany for an undisclosed price.

More than once Habben Jansen was asked about the price, and more than once he said the parties involved had agreed not to disclose that information.

“I think we have given a number of arguments on why we believe that investing in Wilhelmshaven makes sense, I think the main argument being that we think that it will strengthen the position of the German ports … and hopefully over time will lead to more cargo coming in to the German ports,” he said.

Habben Jansen also declined to name other port investments Hapag-Lloyd may be eyeing.

“We won’t comment on specific locations, but the logic behind this is I think we have also learned over the last year and a half that it’s very important to have a robust network and that means you should concentrate, especially in transshipment, in a limited number of places. In those places, it’s then important to have control over terminal capacity,” he said, adding that Hapag-Lloyd “will probably consolidate all of our transshipment volume in … 12 or 15 locations around the globe, and it would not be illogical if we do investments in, say, half of those locations or so.”

‘The already congested supply chain is getting congested even further’

Habben Jansen did talk about the continuing high demand for ocean shipping.

“We’ve certainly seen strong demand on the back of the economic upturn and in the course of the first half. As far as we can see right now, we do expect that to continue. We still see today that demand is very strong on most trades, even if it’s definitely driven still very much by the U.S., because that’s where we see the strongest increases, on the trans-Pacific. And if we look at the last couple of months, also the Atlantic has been very strong,” Habben Jansen said.

“The difficulty that we of course all face at this point in time — and that’s not a secret — this strong demand, combined with a whole bunch of COVID-related restrictions and unexpected surge in volume, has led to quite a lot of difficulties in the supply chain.”

Those difficulties include the lack of available containers.

“The worst numbers we have seen so far were in the month of August, where the time that it takes us to get a container back is up about 20%, which also means that we need 20% more containers than we normally need to transport the same amount of volume.

“The same goes for voyage delays,” Habben Jansen said. “We also have seen these delays go up, and if we look at the situation today, we are probably in the peak of the problems. … The already congested supply chain is getting congested even further.”

The Ever Given blockage of the Suez Canal, COVID-caused port shutdowns in China and an earlier-than-usual peak season all have “put a lot of pressure on global supply chains and capacity. In many ports at the moment, capacity remains strained. This is the case in Asia, where we have significant delays when we look at Korea, we have significant delays when we look at China, also Singapore [is] not as smooth as it normally runs. If you go to Europe, especially in the north, [there are] definitely a number of ports where we have very significant waiting times,” he said.

“If we look at the United States, that’s probably where we still have most of the difficulties, not only in LA/Long Beach but also in other ports on the West Coast, but also increasingly at ports on the East Coast, where places like Savannah and New York are heavily congested.”

Habben Jansen said, “On average it takes us today 10 to 15 days longer before we get the box back. That in reality also means that there are quite a few TEUs globally that are currently somewhere in the supply chain that actually should already be at the warehouses of many of the customers.”

He reiterated that port congestion is not limited to the United States. “On a global basis, we see that pretty much every ship in the Hapag-Lloyd network needs to wait longer before it gets into any port. Those are significant effects.”

The supply chain problems extend beyond ports, Habben Jansen noted. “Let’s not forget that these difficulties are in many cases not limited to the ports only, but we also have bottlenecks on inland transportation. The most obvious bottlenecks, they’re definitely in the U.S., but also in places like the U.K., and in some places in Europe we also see that shortage of available inland capacity [is] prominent.”

He said Hapag-Lloyd has “implemented quite a lot of countermeasures to try and limit the impact on our customers and also to improve service quality.”

“We tried to move capacity to those places where it is needed the most. We’ve also tried to reroute cargo to alternative gateways because sometimes it is better to go to another port if you can berth there upon arrival rather than wait outside for a couple of days. We bought secondhand tonnage, we chartered extra ships, we deployed extra loaders. And we have ordered, in particular, a large number of additional containers,” Habben Jansen said.

This past spring Hapag-Lloyd ordered standard and refrigerated boxes to carry 210,000 twenty-foot equivalent units to combat “severe imbalances” caused by the shortage of containers around the world.

“We have been out to outinvest that problem, if you want. We have added several [hundred] thousand TEUs to our fleet, and I would say that today … that situation around the boxes is pretty much back to normal,” Habben Jansen said.

“In addition to that, we’ve also added people. We’ve added IT capacity. We’ve also developed a number of new digital services that have been launched over the last couple of months [to] allow customers to have better visibility where they actually can and cannot book, and it also allows us to get quicker feedback to our customers on things that are possible and not possible,” he said.

Spot rates and surcharges

Hapag-Lloyd is among the ocean carriers that have agreed “given where the market is today, we should not, even if capacity is very tight and supply and demand would allow us to do that, not raise spot rates any further, which we will abide by until further notice. The same goes for new surcharges,” Habben Jansen said.

Surcharges will come back into play, “but that will not be done today or tomorrow,” he said, advocating a change in the way fees are levied.

“They should be related to enforcing better behavior. If you have a very high no-show ratio, you should probably pay something like a cancellation fee. We at some point need to go and do our utmost to simplify those things,” Habben Jansen said. “Or if you always deliver us higher weight than you declare, then I think it’s fair that you have to pay extra for that. So I think our charges need to go more in the way we drive the right behavior between us.”

He believes there should be a clear understanding of what is expected from both carrier and shipper.

“For an example, if we ask people to bring their containers into the terminal 24 or 48 hours before departure of the ship, if the documentation is not complete before that time, then we will not load that cargo anymore. This all fits into becoming more professional between carrier and shipper. That’s probably, if we look back two or three years from today, that’s probably a good thing that this crisis will have brought,” Habben Jansen said.

Big ships and sustainability

Habben Jansen said “better results” have enabled Hapag-Lloyd to modernize its fleet.

“We have placed a number of orders to renew our fleet and also that’s where Hapag-Lloyd is not an exception. The global orderbook is currently I think a little bit north of 20%. It will take some time, though, before all those ships are going to be delivered,” he said.

Hapag-Lloyd has ordered 12 ships, each with a capacity of more than 23,500 TEUs, at a total cost of $852 million.

“Apart from investing in our fleet, we have also invested in other key areas of our business,” he said. “We’ve done quite a lot of things to boost our digital capabilities with the idea that we do try to provide better transparency on vessel departures and arrivals. We’ve opened up a number of new offices in places like Ukraine, Kenya, Senegal, Morocco, [with] a few more in the pipeline. And of course we’ve also closed on the acquisition of [African carrier] NileDutch.”

Habben Jansen said Hapag-Lloyd remains committed to reducing its carbon dioxide emissions by 60%, compared to 2008, by 2030.

“We have to invest in new ships, phase out older ones, try to see what we can do to use alternative fuels, whether that’s biofuel or synthetic fuel or liquid gas or other things. And yes, we want to achieve becoming carbon-neutral or net-zero carbon-neutral, but that will take time. The key thing here will be to get access to alternative fuels,” he said.

“The reality is, though, that the scaling of the production of those vessels will not be all that easy and that will take time. That’s also why we need to continue to invest in R&D, ideally industrywide. For now, we are making a shift to liquid gas as we believe that currently will be quite a good transitional solution, but more importantly, those ships can also, when you look at their machines and their engines, they will allow us to switch to other greener alternatives, and that could be various fuels,” Habben Jansen said.

He was asked if Hapag-Lloyd had a negative outlook on liquefied natural gas as a long-term fuel.

“For the time being, we do not intend to convert more [ships to LNG] because that conversion turned out to be significantly more expensive than we originally had hoped. It doesn’t mean that if we find another way to do it, we might still consider it, but for the time being, there’s nothing specifically planned there. In terms of the outlook of LNG, I mean, that has certainly changed over the last couple of quarters. There’s all kinds of reports coming out on that,” Habben Jansen said.

“There was a lot of support for LNG as a transition fuel. And I’d also emphasize that the engines we have in those ships cannot only use LNG but also a number of other liquid fuels, even if some of them we might need to do a little bit of modification,” he continued. “How long LNG will be around, I personally think it’s going to be around for quite a lot longer than many people think, simply because the scaling of production of alternative fuel is going to take quite a lot of time.”

Hapag-Lloyd had said in June that it was focusing on LNG “as a medium-term solution as it reduces CO2 emissions by around 15 to 25% and emissions of sulfur dioxide and particulate matter by more than 90%. Fossil LNG is currently the most promising fuel on the path toward zero emissions.”

Lessons learned

Habben Jansen said the supply chain crisis has taught a number of lessons.

“First of all, trying to stay close to the customer is very important. Also I think we’ve learned that trying to be as transparent as possible is important. Be as digital as you can because that allows people to do more and more things themselves. Make sure that we remain agile and flexible,” he said.

He also gave a tip of the hat to the long-suffering seafarers, “the backbone of global shipping,” and said that the crew change crisis brought to the forefront at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic remains a “very, very tough” situation.

“If we look at the operational challenges that we have, they are currently still very, very significant, and we do not expect to see any normalization until Chinese New Year ’22,” he said. “I would seriously hope that after that, we will see a gradual normalization — until we go into the next peak season of 2022.”

October 8, 2021

Update on China Power Situation

Coal For Christmas

by Tyler DurdenThursday, Oct 07, 2021 – 02:40 PM

Authored by Fortis Analysis via Human Terrain (emphasis ours),

In mid-April 2021, I began receiving reports from sources in China and the United States that certain regions in China had begun to experience ongoing power disruptions at their warehouses and manufacturing facilities. Most notable of these was in south China’s Guangdong megaregion, where in June operations at the Taishan Nuclear Power Plant had become disrupted by a small number of faulty claddings for the fuel rods, ultimately forcing state-owned General Nuclear Power Group to shut down Unit 1 (there are two units) for maintenance and repair. Concurrently, available power imported to the Guangdong region from Yunnan province’s considerable hydroelectric capacity was reduced due to drier-than-expected weather throughout the spring.

Taken together, some estimates are that total power available to the region fell by as much as 15% by June. In response, officials began quietly rationing power to factories, cutting business operation days by 1 or 2 days depending on the facilities’ power requirements.

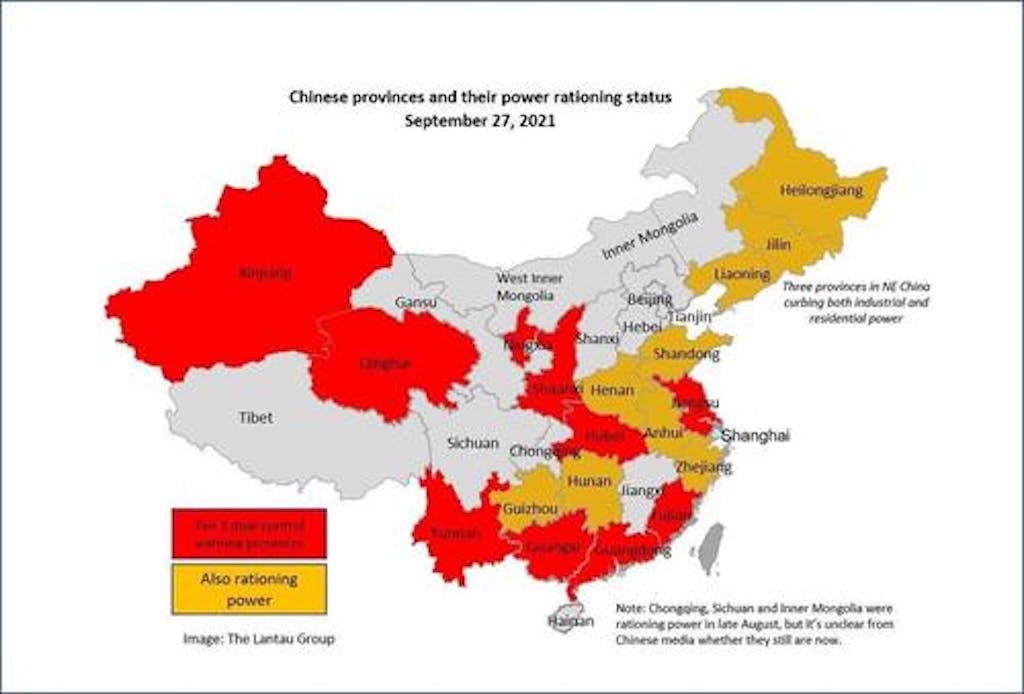

In recent weeks, however, officials have begun a much more aggressive rationing program (Figure 1), with factories in much of Guangdong now seeing only 1-2 days per week of power use allowed. Similar situations are reportedly occurring in Jiangsu, Hubei, and Fujian provinces, all major manufacturing regions. As just one example, one of my US-based import customers has reported that a key supplier in Jiangsu is down to a single day per week of power availability. Limited-but-expanded power rationing is also occurring in Zhejiang, Shandong, Liaoning, and other important heavy industrial, chemical, and energy-product hubs.Figure 1 – Chinese Province Power Rationing Regime – Courtesy of The Lantau Group

The primary causes of power disruptions are the aforementioned reduced availability of hydroelectric power in much of southern China, as well as limited supplies of coal due to the ongoing China/Australia trade dispute. The latter cause is expected to be more sustained in impact, as the year-long embargo by China on Australian thermal coal has depleted China’s strategic reserves and caused commercial and residential prices to rapidly spike. China imports about 10% of its annual thermal coal needs; of this, Australia was close to 70% of the total prior to the mid-2020 embargo. It is expected that China will be forced to drop the embargo ahead of the fourth quarter, but this is not certain. Reopening its markets to Australian coal imports would be an important stabilizing step for China’s manufacturing base, but would nonetheless take weeks or even months to ramp back up to normal output.

If China does not capitulate on the importation of Australian coal and cannot close the gap with imports from Brazil, South Africa, and the US, the southern region will continue to see constrained power availability, reducing export volumes especially from Shenzhen’s ports, Hong Kong, and Xiamen, as well as Tianjin, Dalian, and Qingdao in the north. We would expect in this scenario to see these ports be utilized by ocean carriers for more transshipments out of Southeast Asia or central China, while export-focused capacity shifts to Ningbo and Shanghai, as well as alleviating significant congestion pressure at Kaohsiung and Busan. Freight rates are anticipated by some maritime industry players to soften somewhat, though a bullish case for barely-reduced rates could be made that a very large backlog of existing cargo and ongoing delays at US and European ports will keep volumes at a high level through Lunar New Year at least, with a strong likelihood of continuing through the ILWU negotiations.

October 8, 2021

Update on China Power Situation

Coal For Christmas

by Tyler DurdenThursday, Oct 07, 2021 – 02:40 PM

Authored by Fortis Analysis via Human Terrain (emphasis ours),

In mid-April 2021, I began receiving reports from sources in China and the United States that certain regions in China had begun to experience ongoing power disruptions at their warehouses and manufacturing facilities. Most notable of these was in south China’s Guangdong megaregion, where in June operations at the Taishan Nuclear Power Plant had become disrupted by a small number of faulty claddings for the fuel rods, ultimately forcing state-owned General Nuclear Power Group to shut down Unit 1 (there are two units) for maintenance and repair. Concurrently, available power imported to the Guangdong region from Yunnan province’s considerable hydroelectric capacity was reduced due to drier-than-expected weather throughout the spring.

Taken together, some estimates are that total power available to the region fell by as much as 15% by June. In response, officials began quietly rationing power to factories, cutting business operation days by 1 or 2 days depending on the facilities’ power requirements.

In recent weeks, however, officials have begun a much more aggressive rationing program (Figure 1), with factories in much of Guangdong now seeing only 1-2 days per week of power use allowed. Similar situations are reportedly occurring in Jiangsu, Hubei, and Fujian provinces, all major manufacturing regions. As just one example, one of my US-based import customers has reported that a key supplier in Jiangsu is down to a single day per week of power availability. Limited-but-expanded power rationing is also occurring in Zhejiang, Shandong, Liaoning, and other important heavy industrial, chemical, and energy-product hubs.Figure 1 – Chinese Province Power Rationing Regime – Courtesy of The Lantau Group

The primary causes of power disruptions are the aforementioned reduced availability of hydroelectric power in much of southern China, as well as limited supplies of coal due to the ongoing China/Australia trade dispute. The latter cause is expected to be more sustained in impact, as the year-long embargo by China on Australian thermal coal has depleted China’s strategic reserves and caused commercial and residential prices to rapidly spike. China imports about 10% of its annual thermal coal needs; of this, Australia was close to 70% of the total prior to the mid-2020 embargo. It is expected that China will be forced to drop the embargo ahead of the fourth quarter, but this is not certain. Reopening its markets to Australian coal imports would be an important stabilizing step for China’s manufacturing base, but would nonetheless take weeks or even months to ramp back up to normal output.

If China does not capitulate on the importation of Australian coal and cannot close the gap with imports from Brazil, South Africa, and the US, the southern region will continue to see constrained power availability, reducing export volumes especially from Shenzhen’s ports, Hong Kong, and Xiamen, as well as Tianjin, Dalian, and Qingdao in the north. We would expect in this scenario to see these ports be utilized by ocean carriers for more transshipments out of Southeast Asia or central China, while export-focused capacity shifts to Ningbo and Shanghai, as well as alleviating significant congestion pressure at Kaohsiung and Busan. Freight rates are anticipated by some maritime industry players to soften somewhat, though a bullish case for barely-reduced rates could be made that a very large backlog of existing cargo and ongoing delays at US and European ports will keep volumes at a high level through Lunar New Year at least, with a strong likelihood of continuing through the ILWU negotiations.

October 4, 2021

Shipping Discussion

An Armor Conspired: the Global Shipping Freeze

Peter C. Earle – October 2, 2021 Reading Time: 13 minutes

Despite numerous personal shortcomings, Jim Morrison of The Doors regularly evinced considerable writing talents. In the poem-song Horse Latitudes, he describes the conditions under which stalled galleons would, drifting listlessly at certain latitudes, jettison cargo so as to make their craft more susceptible to the slightest winds. The lyrics begin as follows:

When the still sea conspires an armor

And her sullen and aborted currents

Breed tiny monsters

True sailing is dead

Cargo vessels no longer raise sails or require wind to fill them, but doldrum-like conditions are rapidly manifesting near ports all over the world. Last week,

[s]ixty-one vessels were anchored offshore on Thursday [September 23rd] waiting to unload cargo as the Port of Los Angeles and the Port of Long Beach…In addition to the anchored ships, 29 were adrift up to 20 miles offshore, meaning they were so far from the coast that their anchors could not reach the ocean floor.

And in the east on Sunday, September 26th,

[The] Port of New York and New Jersey appears to be facing similar issues as West coast ports…Around 24 cargo ships and oil tankers [were] stuck waiting to dock off the coast of Long Island, New York…As of 9pm local time Saturday, the ships appeared to have been stuck in place for hours.

Explanations for the increasing delays include slow loading/unloading times, rising costs of shipping, and capital shortages. All of those explanations are correct but incomplete and insufficiently descriptive. To uncover the root causes and trace their evolution, we must go back to the very beginning.

Nominal Rigidities

First, the foundations. While bottlenecks are occurring everywhere, at present US ports are disproportionately affected. Docking locations along US coasts are among the slowest in the world: not because of size or technological capacity but collective bargaining hindrances. As Dominic Pino recently wrote,

Why are our ports so far behind? Not because we don’t spend enough on infrastructure, as the Biden administration would have you believe. The federal government could spend a quadrillion dollars on ports, and it wouldn’t change the contracts with the longshoreman unions that prevent ports from operating 24/7 (as they do in Asia) and send labor costs through the roof. (Lincicome finds that union dockworkers on the West Coast make an average of $171,000 a year plus free healthcare.) The unions also fight automation at American ports today, “just as they fought containerized shipping and computers decades before that.”

Before the public hysterics, lockdowns, and stay-at-home orders, and even before the first offloading was delayed, nominal rigidities had ossified US port operations and made them particularly vulnerable to even the slightest kinks in supply chains.

Where It Began

As is well documented by now, the effects of nonpharmaceutical interventions sent measures of economic activity plummeting throughout the second quarter of 2020. Unemployment skyrocketed to levels not seen since the Great Depression. The US government countered with stimulus payments via the CARES Act (March 2020), the Consolidated Appropriations Act (December 2020), and the American Rescue Plan (March 2021). Although state governors adopted independent pandemic postures, the spectrum of stringency ran a gambit from less to more binding as exemplified by Florida and North Dakota versus Hawaii and California.

The sudden strangulation of in-person commercial activity, coupled with weeks to months of veritable isolation at home, with trillions of dollars being mailed out led to a consumption binge. This was both well documented and empirically verifiable. Where in normal circumstances modern US consumers tend to purchase services more than goods, the circumstances arising of isolation at home for prolonged periods led to a decisive shift toward purchasing goods: electronics, furniture, exercise equipment, home improvement items, and so on.

US GDP (quarterly, chained 2012 dollars, 2019 – present)

It is in the sudden, stimulus-fueled rise in demand falling upon decreasing supply where, in summer and fall of 2020, strains began to wend their way through shipping processes.

Intermodal Transport

Intermodal transport has its roots in the growth of trade in the 19th century, but like so much of what makes the modern world “tick,” it goes mostly unobserved and almost entirely unappreciated. The standardization of shipping containers in such a way that they can move from trucks to ships to aircraft, barges, and trains with a minimum of effort is a feat of technology and international coordination.

US Personal Consumption Expenditures, Chain Type Price Index (2016 – present)

Throughout the fall of 2020 and winter of 2021, the US economy was expanding out of the artificial recession imposed in the spring and early summer of 2020. (It bears noting that even in the latter part of 2020 certain US states were still restricting movement, limiting gatherings, and fining employers.) This expansion of activity resulted in the first episodes witnessing a shortage of shipping containers in February 2021.

The Ever Given and the Suez

On Tuesday, March 23, 2021, the Ever Given–a 1,300 foot, 200,000 tonne container ship carrying over 18,000 containers–became lodged in the Suez Canal. (The canal has closed a handful of times.) The blockage is believed to have occurred when the combination of an uncommonly strong gust of wind and preoccupied guidance led to the fore of the ship running aground, wedging it across the canal at an angle.

In this one development, some 12% of global trade was held up for 6 days: just under $10B dollars worth of goods and over one million barrels of oil. When the ship was finally freed, shipping journal Lloyd’s List estimated that some 450 ships were waiting to traverse the canal.

The damage associated with the accident includes the numerous and uncountable cost of delays, the estimated reduction of annual global trade growth (0.2 to 0.4 percentage points), and the leap in the cost of chartering vessels to go around the Horn of Africa (47%). But also, the role that the Suez blockage played in making each of the subsequent transportation snags all the more severe.

Shipping Containers Dwindle

At this point, the combination of rising demand and slowing sea traffic began revealing itself in a paucity of available shipping containers.

Intermodal transport, which contemplates the use of standardized containers that readily transfer between air, sea, rail, and highway conveyance, is perhaps the most underappreciated factor in the globalized economy. Standard dimensions permit planning and maximizing capacity in advance, giving logisticians the ability to capitalize upon changes in the course of shipment. The ability to move a container from train to aircraft to ship results in efficient lading, which has contributed to lower costs and faster delivery times.

The global shipping container inventory tends toward a rough equilibrium state which takes into account surges in demand; the containers tend to last about 12 years, and are produced at a rate generally matching their retirement of some 6 to 8% per year. The greatest and most predictable surge of use occurs between September and December as retailers stock inventories in anticipation of the Thanksgiving to New Year’s surge in consumption.

But by the early spring of 2021, with containers filling rapidly in response to Covid-related demand (both lockdowns and reopenings) and additional stimulus payments, available containers and container space became scarcer. Dwindling supply, predictably, was signaled by worldwide container prices. There are markets for newly built shipping containers as well as exchanges where used containers can be acquired. Between early and late 2020, new shipping container prices rose from roughly $1,800 to $2,500 CEU; but roughly one month after the week-long Suez blockage the first of several spikes was witnessed.

The price for a new container is now $3,500 per cost equivalent unit (CEU, a measure of the value of a container as a multiple of a 20-foot dry cargo unit)…[while] recent price gains have been more extreme in the used container market. Container xChange reported that the price of used containers in China has nearly doubled from $1,299 per CEU in November [2020] to $2,521 in March [2021].

As to why production of new containers didn’t ramp up to meet surging demand, there are several perspectives. If the elevated demand was expected to be temporary, it’s possible that container firms didn’t see the point in increasing output. Another view holds that a rare opportunity to earn outsized profits in a normally staid business was capitalized upon by the producing firms.

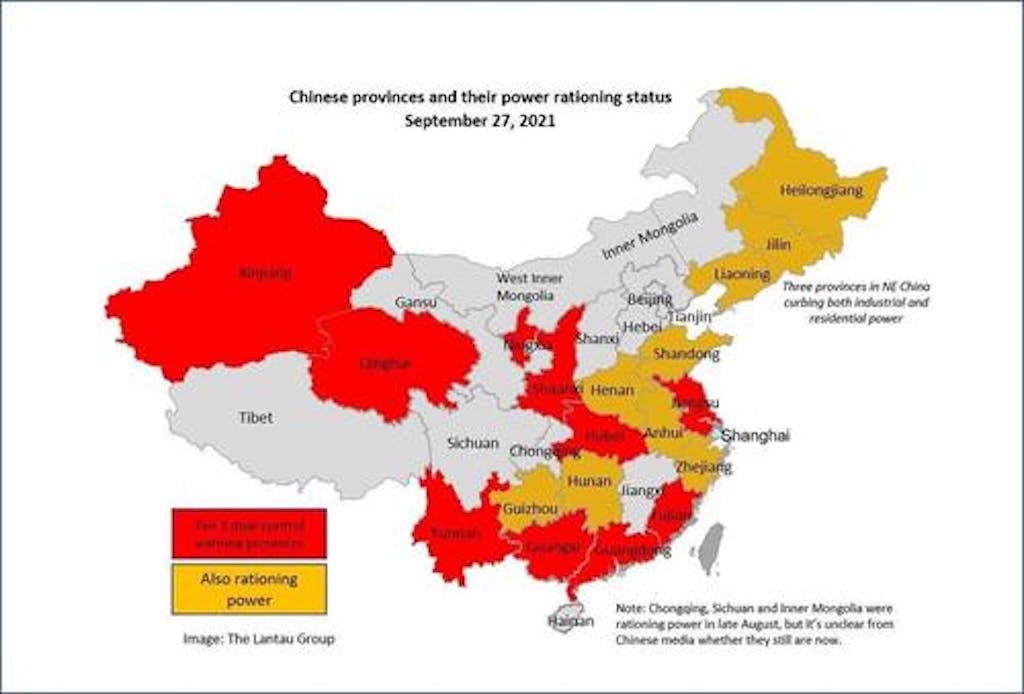

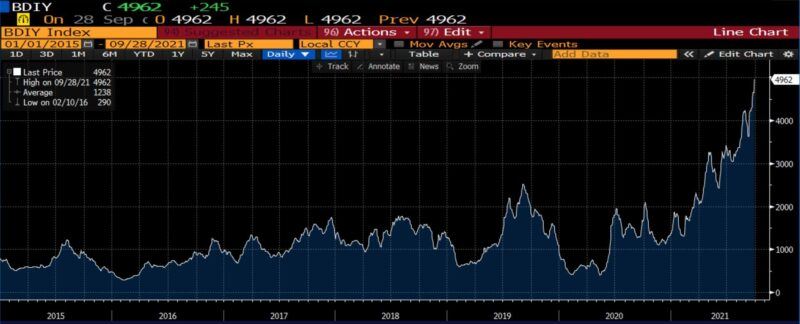

Baltic Dry Index (2015 – present)

Yantian Closes

In late May 2021 Yantian, a Chinese port about 50 miles north of Hong Kong shut owing to a number of Covid infections among dockworkers. Authorities halted operations for almost a week, which at a daily operating capacity of 30,000 20-foot containers per day, created a tremendous backlog. The ripple effect saw not only a pileup of unsent goods at that port, but the rerouting of Yantian-bound container ships to other ports straining capacity, creating further delays, and tying up more containers. By Thursday, June 17th,

[t]he congestion in Yantian ha[d] spilled over to other container ports in Guangdong, including Shekou, Chiwan, and Nansha…The domino effect is creating a huge problem for the world’s shipping industry…As of Thursday, more than 50 container vessels were waiting to dock in Guangdong’s Outer Pearl River Delta…[But] the snag in operations in Yantian alone is concerning [delaying] more than the total volume of freight impacted by the six-day closure of the Suez Canal in March.

The price associated with shipping goods spiked, with the cost of sending 40-foot containers from Shanghai to Rotterdam increasing over 500% to $11,000 or more. The breach of the $10,000 rate marked a turning point; and it was at this point that, en masse, major shipping companies began alerting their clients of substantial delays, rising costs associated with routing changes, and higher prices associated with acquiring containers. Firms dependent upon ocean shipping began to do something they had been unaccustomed to: considering, and in some cases seizing upon, the newly-developed cost savings associated with air and rail transport.

Containers and Ships Vanish

As container availability dissipated and warehouses near ports overflowed, some shipping firms chose to use the scant containers in their possession as makeshift storage space on docks and truck/rail terminals. And by June 2021,

Indian exporters to North America and Europe [were] complaining that the wait times to find a shipping container [could] stretch as long as three weeks. British exporters say the shortage [had] delayed shipments to east Asia for up to two months. And in the meantime, container prices…nearly doubled.

On June 14th, Home Depot supply chain managers

realized that it was time to charter its own vessel. “We have a ship that’s solely going to be ours and it’s just going to go back and forth…100% dedicated to Home Depot,” Chief Operating Officer Ted Decker said…The company [had] been reduced to bringing in items by air…as domestic demand surge[d].

Brokerage prices for short- and long-term charters began to surge. Whether awakened to this possibility by the Atlanta-based retailer or having arrived at the same conclusion independently, over the following weeks Walmart, Ikea, and scores of other large firms entered the private charter market.

Pallets Join Containers

All this was soon accompanied with a new problem deriving from yet another pandemic policy side effect: a pallet deficiency. The price of lumber had, owing to the effect of stay-at-home orders on sawmills and home improvement projects owing to lockdowns, surged roughly five-fold between January 2020 and May 2021. (By one account, an estimated 46% of US hardwood lumber production goes toward pallets.)

Front-month lumber futures price (Jan 2020 – May 2021)

In fact, the international shipment of certain types of goods requires being seated upon pallets within shipping containers. Unbeknownst to materially all the world not familiar with the nuance of international trade, pallets are, just like the shipping containers they are regularly coupled with, nothing short of an integral cog:

Companies…have literally designed products around pallets…There is a whole science of “pallet cube optimization,” a kind of Tetris for packaging; and an associated engineering filled with analyses of “pallet overhang” (stacking cartons so they hang over the edge of the pallet, resulting in losses of carton strength) and efforts to reduce “pallet gaps” (too much spacing between deck boards). The “pallet loading problem,”–or the question of how to fit the most boxes onto a single pallet–is a common operations research thought exercise.

And as reported on ShipLilly, a shipping and logistics blog on June 9th, 2021,

The cost of raw lumber has doubled and sometimes nearly quadrupled. Lumber price increments have exponential impacts on the cost of manufacturing wood pallets. Manufacturers are passing on these costs by way of increased asking prices…If pallets are available, a buyer can expect to pay 400% more.

Hastily-improvised workarounds swing into action, including repairing old pallets, building new pallets from discarded lumber, new loading schemes, and employing alternative means of elevating cargo, including plastic or concrete. This incidentally, put the shipping industry in direct competition with agricultural interests, as transporting produce is also dependent upon pallet availability and prices.

Ningbo Closes

It is yet too early to call what occurred in mid-August 2021 the capstone event, but for now that appellation suffices.

With the detection of a single Covid infection among workers–a worker reported to be 34-years-old, fully vaccinated, and asymptomatic–a large portion of China’s massive Ningbo-Zhoushan Port closed for nearly two weeks. The impact of the partial shutdown of the third largest port in the world not only derailed the slow recovery from the Yantian cessation, but

stretched across the Pacific Ocean to Long Beach port in Los Angeles, where more than 30 ships were waiting to get into port to offload…elsewhere in Southeast Asia, anchored ships off Vietnam’s largest two ports rose to six above the median.

WCI Composite Container Freight Benchmark Rate (per 40-foot, 2010 – present)

Necessity being not only mother but father, sibling, master, and servant to invention, creative solutions poured forth from the private sector. Large and small firms began chartering smaller ships to fit into smaller, less congested ports. And many corporate logistical programs, including that of Peloton, began dividing shipments into optimized shipping categories among train, truck, air, and sea routes. And on the demand side, retailers began stockpiling: withholding goods from store shelves and online listings in anticipation of the coming holiday season. (Amazon’s decision to purchase 11 Boeing 767s earlier this year looks sagacious in retrospect.)

Early in the pandemic, it was noted that the impact of lockdowns would be proportionately more devastating for smaller firms. And as such, that consolidation and concentration–the frequent target of the very same left political thought that drove nonpharmaceutical interventions–were likely outcomes. And that is indeed the case arising of these secondary and tertiary effects.

[S]upply chain snags are likely to add dominance to big-box retailers while cutting out smaller companies that don’t have the extra funds to charter their own vessels or ship via cargo planes. “Whenever we have a constrained supply like this it’s always the big dogs that win,” Douglas Kent, executive vice president of strategy and alliances at the Association of Supply Chain Management [said]. “The smaller firms just don’t have the capital to keep up. They’re already in survival mode. They’re going to have to pass on these costs to customers and risk losing out to big-box retailers that can absorb these costs themselves. As a result we will likely see the shuttering of more companies due to these ongoing issues.”

Predictably, container carriers are seeing a windfall. The same 40-foot container which cost, at most, $2,000 to ship goods from Asia to the US will now cost $25,000 if the exporting firm has guaranteed (or the importing firm paid for) on-time delivery. In 2020, the shipping industry earned an estimated $15 billion in profit; this year, the number is likely to top $100 billion.

Ongoing Port Congestion

Throughout September 2021 ports all over the United States have been experiencing record ship delays. By September 11th, the logjam at the Los Angeles ports exceeded 50 ships carrying as much cargo as was previously seen in a month. After peaking at 73 ships on Sunday, September 19th, half a week later there were still 62 ships waiting to dock and offload. That’s up from an average of zero to one (on a particularly busy day), pre-Covid. And among them were craft and crew that had been waiting for as long as three weeks.

Drewry Hong Kong to Los Angeles Container Rate (40-foot, 2015 – present)

Yet even addressing the rigidities and stickiness discussed in an earlier section–maximum daily/weekly work hours and wages set by long-standing collective bargaining agreements–is mostly unhelpful, owing to the vast number of moving parts in the international supply chain.

[L]onger hours do little to address the backlog when truckers and warehouse operators have not similarly extended their hours. It’s not optimal for truckers to pick up their loads at night, especially when they’d have to find alternative places to store the goods [as] warehouses are not open at night.

Additionally, broader labor shortages arising from the payment of Federal unemployment bonuses have been impacting every link in the international logistical chain. “Many companies,” Business Insider reported, “have fewer workers [now] than before the pandemic started but face significantly more work due to the boom in demand for goods.”

The Armor Yet Conspires

As of last week the spot rate for container rates was up 731% over the average of the past five years. As shipping cancellations have risen amid rapid changes in logistical plans, some ocean shipping firms are now requiring full payment up front, adding yet another level of difficulty to an increasingly intractable state of affairs. Amid this, retailers are attempting to stock up for the end-of-year holidays. Predictions regarding a return to normalcy range from 2022 to as late as 2023. Companies including Nike have already warned that certain products are likely to be unavailable before the holiday season.

The effect of blow after blow to global trade on the availability of goods is most visible in the following graph.

Manufacturing and Trade Inventory/Sales Ratio (2015 – present)

Three observations may be made: first, that for some years, the ratio of business inventories to sales in manufacturing, retail, and wholesale trade has been fairly steady. Second: when Covid initially struck, the ensuing policies resulted in the ratio of business inventories to sales rocketing to all-time highs. (Which is to say: goods piled high as consumption plummeted.) And finally, consumption soon soared as people at home began spending, fueled by boredom and stimulus payments. Businesses have reopened and many have kept up with demand, but the ongoing problems of shipping described heretofore have led the inventory-to-sales ratio dropping to all-time lows.

This week it was reported that the fourth largest port in the US, in Savannah, GA, 20 ships are now delayed. “Dwell times” – the time elapsing between containers arriving at the port and departing by truck or train – have increased from four to as long as twelve days. Globally, a host of other quandaries potentially lie ahead. Typhoons, a shortage of truck drivers in Europe, government responses to new outbreaks of Delta and subsequent Covid variants all threaten to worsen the shipping crisis from where it currently stands.

CTS Average Global Container Price Index (Jan 2016 – July 2021)

There is an unavoidable price for the ceaseless avalanche of goods and services falling around us: it is exposure to an arrant, inherent level of complexity. Only the coordination of a superabundant array of prices, timing, capacity, and information keeps the globally-integrated supply chain functioning. A single, small misstep or error increases the likelihood of subsequent problems at every juncture in the process. The “two weeks to flatten the curve” decision along with other shortsighted, unnecessary (and, as it turns out, ineffective) policy options has generated countless knock-on effects. Those now include shortages of shipping containers, long and increasing port delays, a growing scarcity of essential supply chain components, insufficient labor, higher prices, and a mounting undersupply of final goods. While it may prove hyperbolic, for the first time this week the description of a “global transport system collapse” was employed.

Science and engineering have brought about an era in which doldrums no longer vex modern day mariners. Owing to innovation and entrepreneurship, there are no longer horse latitudes where payloads are dumped overboard by desperate crews. Yet those conditions have reemerged, borne not of nature but of power, mindlessly exercised. The idea that an economy could be indiscriminately shut down and turned back on without far-reaching consequences, as if a light switch or lawn mower, is utterly damnable. It could only come from the mind of an individual, or body of individuals, with no understanding of or consideration for the extraordinary interdependence of the productive sector.