Current Affairs

June 10, 2022

Inventories are in the News

“The Demand For Random Crap Suddenly Vanished, Taking Everyone By Surprise”

by Tyler DurdenThursday, Jun 09, 2022 – 07:00 PM

By Rachel Premack of FreightWaves

At the beginning of 2022, things were economically pretty peachy. Too peachy, one could argue: People were buying so much stuff that our ports and terminals could barely handle the massive import volume. Companies were desperate for someone, anyone, to come work for them. And movie theaters, offices, planes and other locales many eschewed during the pandemic were poised to bounce back; the omicron wave appeared mild compared to previous bouts of the coronavirus.

The vibes were good. Now, the vibes are completely terrible.

More and more spooky recession signs are cropping up seemingly every day, ranging from cooling housing starts to meek GDP growth, all amid the Fed tightening rates. Record-setting inflation – particularly for gas – is only adding to the premonitions, as Vox’s Emily Stewart wrote Wednesday in a piece aptly titled “The bad vibes economy.” But even as things feel bad, many still cast doubt that we’re headed for a recession this year, pointing out persistently low unemployment and the fact that certain indicators, while not as strong as the beginning of this year, are still unusually healthy.

No one is shocked that what goes up must go down. What’s shocking us all is how quickly the situation changed.

Glum transportation indicators confirm the bad vibes

A downturn, if not a full-on recession, is clear in the transportation world. While the rest of the economy debates whether things are that bad, it’s been clear for months to logistics providers that the situation has worsened — and the velocity of that change is still stunning.

The cost to move a container from Asia to a major port in North America or Europe has sunk by 23% since the beginning of this year, according to maritime research firm Drewry. Spot rates have plummeted even faster; marketplace Freightos said rates from China to the West Coast are down 38% month-over-month. FreightWaves forecast this week that ocean shipping volumes will “drop off a cliff” by this summer, based on slumping bookings out of China.

Spot van rates in trucking are down 31% since the beginning of this year, with some truck drivers reporting that rising diesel and plummeting rates have already harmed their business.

Even our mighty railroads are reporting a 3% year-to-date decline in volumes across the board, with only carloads of coal, chemicals and “stone, sand and gravel” (aka, frac sand) increasing.

The pullback in transports has been quicker and swifter than anyone imagined. In the ocean world, carriers have deployed more vessels than ever before, according to research firm Sea-Intelligence. In March, Sea-Intelligence forecast carriers to increase their capacity following Chinese New Year by 20% over 2019 levels. Asia-East Coast services were forecast to grow an eye-popping 40%.

And in trucking, small carriers flooded the market. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the number of trucks available to haul a load is up 10%.

Transporters built up record capacity to move loads that are suddenly shrinking. Even if volumes merely settled to pre-pandemic marks, rather than collapsing to a 2008-like recessionary volume, carriers would still be in trouble.

And this isn’t a trend that’s exclusive to transportation.

Retailers are a little embarrassed right now

Walmart, Amazon, Home Depot, Best Buy and most every other retailer are having their own mismatch of supply and demand. They stocked up too much this past year. Now they’re struggling with something called “inventory bloat.” It is even more painful than regular bloating, I imagine, if you are a shareholder in a large retail firm.

While we were buying more and more crap, seemingly without any regard for our dwindling savings, our favorite retailers were doing anything to get more product in.

At some point this year, though, the thirst for buying stuff finally quenched. Some of us got spooked by inflation, others got hit by a hefty tax bill and still others decided to spend their apparently boundless cash on trips abroad and fine dining. Or some weird combination of the three.

The retailers weren’t aware that we were all going to stop ravenously buying this quarter, apparently. They quietly kept amassing their own inventories, many of which were still depleted from 2020 and 2021. And concern over another black swan after years of oddities – trade wars, the pandemic and so on – probably drove many transportation managers to keep ordering stuff. Just in case.

Retailers realized this spring that they built up too much. Amazon said in an April call to investors that it had to scale back after doubling its warehouse footprint. Bloomberg reported weeks later that the mega-retailer was quietly trying to end or sublease at least 10 million square feet of warehouse space. It was a stunning about-face for the company that many investors believed had not only endless growth but an unmatchable logistics machine.

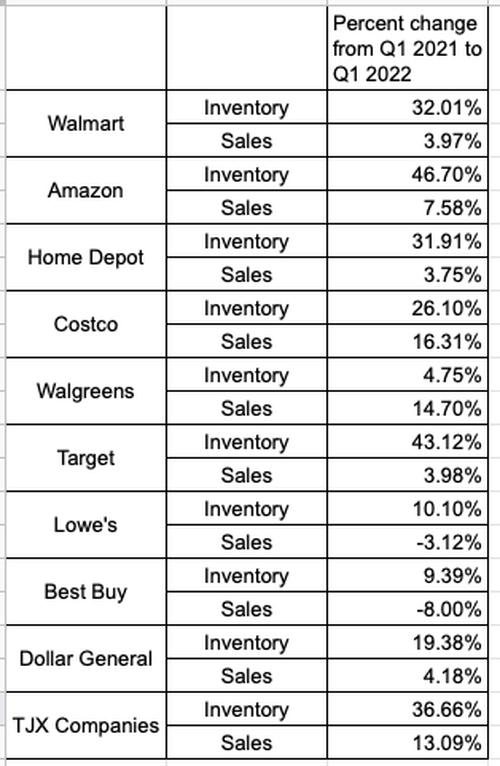

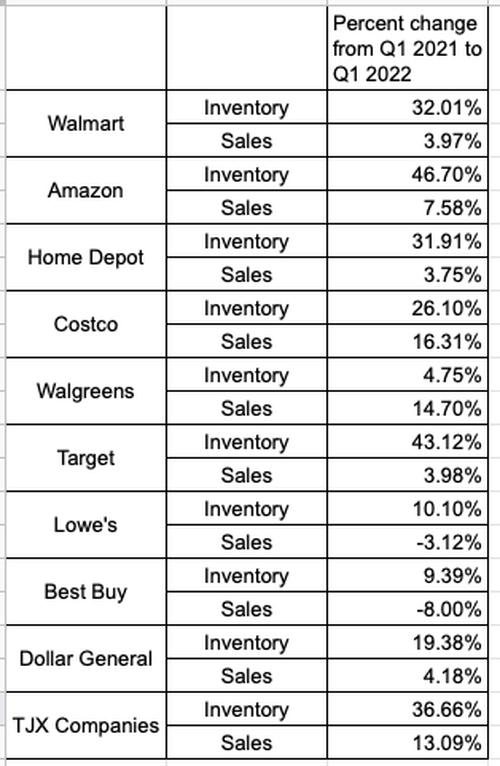

It’s not just warehouse space that Amazon loaded up on – it’s the stuff in the warehouses. According to federal filings concerning the first three months of 2022, the value of Amazon’s total inventories increased 47% compared to the same period last year. But its North America net sales only popped 8%.

Amazon was hardly alone in its uncomfortable first-quarter report. Walmart’s inventory jumped 32% from the previous year, compared to a 4% increase in sales. Best Buy’s inventories increased 9%, while sales declined by 8%.

Target really wants you to buy a bunch of televisions and lawn chairs

America’s top retailers messed up – particularly the ones that focus on durable goods rather than groceries. Most of them released their earnings reports last month, saw shares take a beating and moved on.

Target followed that at first. Its earnings report on May 18 fell short of investor expectations, with an anticipated profit margin of 5.3%. Over-the-top inventories of kitchen appliances and electronics were the top culprit. Its stock sank by 25%.

Then, the mega-retailer did something no one was expecting. On Tuesday, Target told investors it anticipated a profit margin more around 2%. It would slash prices on certain goods and cancel incoming orders. It’s highly unusual for a company to slash its profit expectations within weeks of its earnings report.

Target said in its Tuesday press release that the profit slash comes from a need to “right-size” inventories. People aren’t buying items like televisions, outdoor furniture and kitchen appliances like they were last year. Those are some of the delicate, bulky items Target paid dearly to bring over from Asia in 2021, amid record-high shipping rates.

It’s all leading to what Forbes’ Madeline Halpert called “markdown mania,” and not just at Target. Gap is hawking $60 leggings for just $12. Target is selling televisions for 25% off and patio sets at a 52% markdown. In total, shares in consumer staples stocks have tumbled by about 9% from mid-April highs, while consumer discretionary shares are down by about 20% over the same period.

Few of us in the logistics world were surprised. After all, if trucks and ships are moving less stuff, it’s a sign that consumers aren’t buying as much and that manufacturers have curtailed their output.

Sometimes it can be hard for us who toil in logistics to get the attention of lofty economists and traders. Even though I write about the companies that move everything we eat, wear, drink and most any other verb you could think of, I’m still told that I cover a niche industry. The ongoing downturn in trucking seems like it would only affect truckers – never mind the fact that a trucking recession has preceded nearly every recession since the 1970s, per research from freight brokerage Convoy.

The demand for random crap suddenly vanished, taking everyone by surprise

As my colleague Mark Solomon wrote last month on this “inventory bloat,” it’s challenging to forecast demand – even if you’re one of the biggest retailers in the world. We can return to that key metric of inventories-to-sales ratios, which, conveniently, the federal government tracks.

We generally don’t like an inventories-to-sales ratio that’s too high – it indicates that people don’t have the cash to buy stuff. But if it’s too low, like it was through much of 2020 and 2021, it means that there isn’t any stuff to buy. See: The “everything shortage” that dominated headlines last year.

As you can see, the inventories-to-sales ratio is still very low, even if it is creeping up from the nadir of last year. That gives credence to some who argue that a recession isn’t in the cards for this year and could explain why the National Retail Federation declared on Wednesday that it expected port volume to roughly match the crazy numbers seen in 2021. (FreightWaves’ own research, which JPMorgan analysts lent credence to in a Wednesday note to investors, counters that.)

The ratio is more marked when you look at the major consumer goods, as Solomon reported (emphasis mine):

Furniture, home furnishings and appliances, building materials and garden equipment, and a category known as “other general merchandise,” which includes Walmart and Target, among others, reported higher inventory-to-sales ratios, according to government data analyzed by Michigan State.

For the latter sectors, the change has happened fast, according to Jason Miller, logistics professor at MSU’s Eli Broad College of Business. As of November, inventory-to-sales ratios were at pre-COVID levels, Miller said. They have since exploded upward.

To end, I’d like to emphasize that the vibes are abruptly off and no one really knows what’s happening. My colleagues who went to the Gartner supply chain conference in Florida this week found that executives were confused and not feeling very zesty. Transportation managers canceled orders in early 2020 predicting a recession, then found their hastiness left shelves empty and consumers furious. Now that they’ve built back up, customers aren’t buying anymore and their balance sheets are destroyed.

The whiplash is baffling.

https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/demand-random-crap-suddenly-vanished-taking-everyone-surprise

June 10, 2022

Inventories are in the News

“The Demand For Random Crap Suddenly Vanished, Taking Everyone By Surprise”

by Tyler DurdenThursday, Jun 09, 2022 – 07:00 PM

By Rachel Premack of FreightWaves

At the beginning of 2022, things were economically pretty peachy. Too peachy, one could argue: People were buying so much stuff that our ports and terminals could barely handle the massive import volume. Companies were desperate for someone, anyone, to come work for them. And movie theaters, offices, planes and other locales many eschewed during the pandemic were poised to bounce back; the omicron wave appeared mild compared to previous bouts of the coronavirus.

The vibes were good. Now, the vibes are completely terrible.

More and more spooky recession signs are cropping up seemingly every day, ranging from cooling housing starts to meek GDP growth, all amid the Fed tightening rates. Record-setting inflation – particularly for gas – is only adding to the premonitions, as Vox’s Emily Stewart wrote Wednesday in a piece aptly titled “The bad vibes economy.” But even as things feel bad, many still cast doubt that we’re headed for a recession this year, pointing out persistently low unemployment and the fact that certain indicators, while not as strong as the beginning of this year, are still unusually healthy.

No one is shocked that what goes up must go down. What’s shocking us all is how quickly the situation changed.

Glum transportation indicators confirm the bad vibes

A downturn, if not a full-on recession, is clear in the transportation world. While the rest of the economy debates whether things are that bad, it’s been clear for months to logistics providers that the situation has worsened — and the velocity of that change is still stunning.

The cost to move a container from Asia to a major port in North America or Europe has sunk by 23% since the beginning of this year, according to maritime research firm Drewry. Spot rates have plummeted even faster; marketplace Freightos said rates from China to the West Coast are down 38% month-over-month. FreightWaves forecast this week that ocean shipping volumes will “drop off a cliff” by this summer, based on slumping bookings out of China.

Spot van rates in trucking are down 31% since the beginning of this year, with some truck drivers reporting that rising diesel and plummeting rates have already harmed their business.

Even our mighty railroads are reporting a 3% year-to-date decline in volumes across the board, with only carloads of coal, chemicals and “stone, sand and gravel” (aka, frac sand) increasing.

The pullback in transports has been quicker and swifter than anyone imagined. In the ocean world, carriers have deployed more vessels than ever before, according to research firm Sea-Intelligence. In March, Sea-Intelligence forecast carriers to increase their capacity following Chinese New Year by 20% over 2019 levels. Asia-East Coast services were forecast to grow an eye-popping 40%.

And in trucking, small carriers flooded the market. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the number of trucks available to haul a load is up 10%.

Transporters built up record capacity to move loads that are suddenly shrinking. Even if volumes merely settled to pre-pandemic marks, rather than collapsing to a 2008-like recessionary volume, carriers would still be in trouble.

And this isn’t a trend that’s exclusive to transportation.

Retailers are a little embarrassed right now

Walmart, Amazon, Home Depot, Best Buy and most every other retailer are having their own mismatch of supply and demand. They stocked up too much this past year. Now they’re struggling with something called “inventory bloat.” It is even more painful than regular bloating, I imagine, if you are a shareholder in a large retail firm.

While we were buying more and more crap, seemingly without any regard for our dwindling savings, our favorite retailers were doing anything to get more product in.

At some point this year, though, the thirst for buying stuff finally quenched. Some of us got spooked by inflation, others got hit by a hefty tax bill and still others decided to spend their apparently boundless cash on trips abroad and fine dining. Or some weird combination of the three.

The retailers weren’t aware that we were all going to stop ravenously buying this quarter, apparently. They quietly kept amassing their own inventories, many of which were still depleted from 2020 and 2021. And concern over another black swan after years of oddities – trade wars, the pandemic and so on – probably drove many transportation managers to keep ordering stuff. Just in case.

Retailers realized this spring that they built up too much. Amazon said in an April call to investors that it had to scale back after doubling its warehouse footprint. Bloomberg reported weeks later that the mega-retailer was quietly trying to end or sublease at least 10 million square feet of warehouse space. It was a stunning about-face for the company that many investors believed had not only endless growth but an unmatchable logistics machine.

It’s not just warehouse space that Amazon loaded up on – it’s the stuff in the warehouses. According to federal filings concerning the first three months of 2022, the value of Amazon’s total inventories increased 47% compared to the same period last year. But its North America net sales only popped 8%.

Amazon was hardly alone in its uncomfortable first-quarter report. Walmart’s inventory jumped 32% from the previous year, compared to a 4% increase in sales. Best Buy’s inventories increased 9%, while sales declined by 8%.

Target really wants you to buy a bunch of televisions and lawn chairs

America’s top retailers messed up – particularly the ones that focus on durable goods rather than groceries. Most of them released their earnings reports last month, saw shares take a beating and moved on.

Target followed that at first. Its earnings report on May 18 fell short of investor expectations, with an anticipated profit margin of 5.3%. Over-the-top inventories of kitchen appliances and electronics were the top culprit. Its stock sank by 25%.

Then, the mega-retailer did something no one was expecting. On Tuesday, Target told investors it anticipated a profit margin more around 2%. It would slash prices on certain goods and cancel incoming orders. It’s highly unusual for a company to slash its profit expectations within weeks of its earnings report.

Target said in its Tuesday press release that the profit slash comes from a need to “right-size” inventories. People aren’t buying items like televisions, outdoor furniture and kitchen appliances like they were last year. Those are some of the delicate, bulky items Target paid dearly to bring over from Asia in 2021, amid record-high shipping rates.

It’s all leading to what Forbes’ Madeline Halpert called “markdown mania,” and not just at Target. Gap is hawking $60 leggings for just $12. Target is selling televisions for 25% off and patio sets at a 52% markdown. In total, shares in consumer staples stocks have tumbled by about 9% from mid-April highs, while consumer discretionary shares are down by about 20% over the same period.

Few of us in the logistics world were surprised. After all, if trucks and ships are moving less stuff, it’s a sign that consumers aren’t buying as much and that manufacturers have curtailed their output.

Sometimes it can be hard for us who toil in logistics to get the attention of lofty economists and traders. Even though I write about the companies that move everything we eat, wear, drink and most any other verb you could think of, I’m still told that I cover a niche industry. The ongoing downturn in trucking seems like it would only affect truckers – never mind the fact that a trucking recession has preceded nearly every recession since the 1970s, per research from freight brokerage Convoy.

The demand for random crap suddenly vanished, taking everyone by surprise

As my colleague Mark Solomon wrote last month on this “inventory bloat,” it’s challenging to forecast demand – even if you’re one of the biggest retailers in the world. We can return to that key metric of inventories-to-sales ratios, which, conveniently, the federal government tracks.

We generally don’t like an inventories-to-sales ratio that’s too high – it indicates that people don’t have the cash to buy stuff. But if it’s too low, like it was through much of 2020 and 2021, it means that there isn’t any stuff to buy. See: The “everything shortage” that dominated headlines last year.

As you can see, the inventories-to-sales ratio is still very low, even if it is creeping up from the nadir of last year. That gives credence to some who argue that a recession isn’t in the cards for this year and could explain why the National Retail Federation declared on Wednesday that it expected port volume to roughly match the crazy numbers seen in 2021. (FreightWaves’ own research, which JPMorgan analysts lent credence to in a Wednesday note to investors, counters that.)

The ratio is more marked when you look at the major consumer goods, as Solomon reported (emphasis mine):

Furniture, home furnishings and appliances, building materials and garden equipment, and a category known as “other general merchandise,” which includes Walmart and Target, among others, reported higher inventory-to-sales ratios, according to government data analyzed by Michigan State.

For the latter sectors, the change has happened fast, according to Jason Miller, logistics professor at MSU’s Eli Broad College of Business. As of November, inventory-to-sales ratios were at pre-COVID levels, Miller said. They have since exploded upward.

To end, I’d like to emphasize that the vibes are abruptly off and no one really knows what’s happening. My colleagues who went to the Gartner supply chain conference in Florida this week found that executives were confused and not feeling very zesty. Transportation managers canceled orders in early 2020 predicting a recession, then found their hastiness left shelves empty and consumers furious. Now that they’ve built back up, customers aren’t buying anymore and their balance sheets are destroyed.

The whiplash is baffling.

https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/demand-random-crap-suddenly-vanished-taking-everyone-surprise

June 9, 2022

Natural Gas Update

European Gas Soars After US LNG Terminal Explosion Halts Exports For Weeks

by Tyler DurdenThursday, Jun 09, 2022 – 10:50 AM

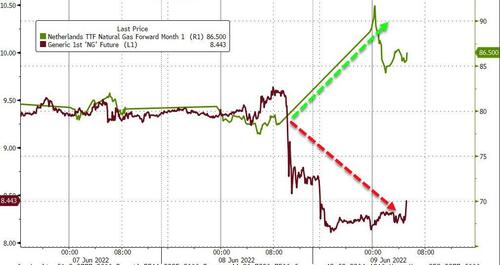

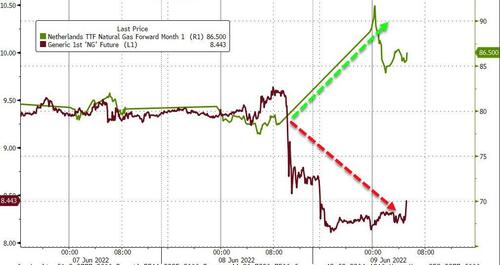

Europe’s natural gas prices jumped Thursday after one of the US’ largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals experienced an explosion on Wednesday and has been shut down. A large share of the terminal’s LNG has been destined for Europe as the continent weens off Russian supplies.

Been in the Freeport area all day for an “incident” at LNG facility on Quintana Island. Freeport PD and witnesses say no doubt about it: it was an explosion. The fire/release has been contained and employees are accounted for. Investigation underway. pic.twitter.com/8wuGEGazb2 — Erica Simon (@EricaOnABC13) June 8, 2022

According to Bloomberg, the Freeport LNG export terminal in Texas will be shuttered for at least three weeks, which will impact 20% of all US LNG exports. In the last four months, 75% of all US LNG exports have been sent to Europe.

“In the last three months, 68% of all Freeport cargoes were delivered into European markets,” said Tom Marzec-Manser, head of gas analytics at ICIS.

Ole Hansen, head of the commodity strategy at Saxo Bank A/S, said the situation at Freeport has upended European gas markets after “calm trading seen in recent weeks.”

Dutch front-month gas, the European benchmark, traded as high as 16% before giving up some gains and trading at 84 euros per megawatt-hour.

After the reports of the explosion, we noted that US natgas was sold due to export halt fears would build supplies on the domestic grid; inversely, EU natgas would soar because of a decline in export shipments.

For those puzzled by the price action, US NatGas’s slump is in response to the prospect that fewer LNG exports would mean more supply domestically, though inversely, it would mean higher prices in Europe since the US has been increasingly sending LNG across the Atlantic to ween European countries off Russian supplies.

Since the incident at Freeport, US natgas prices have plunged 15%.

Analysts at Houston-based energy firm Criterion Research said, “very little information is known about the extent of the damage and how long it will take to repair.”

https://www.zerohedge.com/commodities/european-gas-soars-after-us-freeport-lng-terminal-explosion

June 9, 2022

Natural Gas Update

European Gas Soars After US LNG Terminal Explosion Halts Exports For Weeks

by Tyler DurdenThursday, Jun 09, 2022 – 10:50 AM

Europe’s natural gas prices jumped Thursday after one of the US’ largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals experienced an explosion on Wednesday and has been shut down. A large share of the terminal’s LNG has been destined for Europe as the continent weens off Russian supplies.

Been in the Freeport area all day for an “incident” at LNG facility on Quintana Island. Freeport PD and witnesses say no doubt about it: it was an explosion. 💥 The fire/release has been contained and employees are accounted for. Investigation underway. pic.twitter.com/8wuGEGazb2 — Erica Simon (@EricaOnABC13) June 8, 2022

According to Bloomberg, the Freeport LNG export terminal in Texas will be shuttered for at least three weeks, which will impact 20% of all US LNG exports. In the last four months, 75% of all US LNG exports have been sent to Europe.

“In the last three months, 68% of all Freeport cargoes were delivered into European markets,” said Tom Marzec-Manser, head of gas analytics at ICIS.

Ole Hansen, head of the commodity strategy at Saxo Bank A/S, said the situation at Freeport has upended European gas markets after “calm trading seen in recent weeks.”

Dutch front-month gas, the European benchmark, traded as high as 16% before giving up some gains and trading at 84 euros per megawatt-hour.

After the reports of the explosion, we noted that US natgas was sold due to export halt fears would build supplies on the domestic grid; inversely, EU natgas would soar because of a decline in export shipments.

For those puzzled by the price action, US NatGas’s slump is in response to the prospect that fewer LNG exports would mean more supply domestically, though inversely, it would mean higher prices in Europe since the US has been increasingly sending LNG across the Atlantic to ween European countries off Russian supplies.

Since the incident at Freeport, US natgas prices have plunged 15%.

Analysts at Houston-based energy firm Criterion Research said, “very little information is known about the extent of the damage and how long it will take to repair.”

https://www.zerohedge.com/commodities/european-gas-soars-after-us-freeport-lng-terminal-explosion

June 8, 2022

The New Reality

US Import Demand Is Dropping Off A Cliff

by Tyler DurdenTuesday, Jun 07, 2022 – 07:25 PM

By Henry Byers of FreightWaves

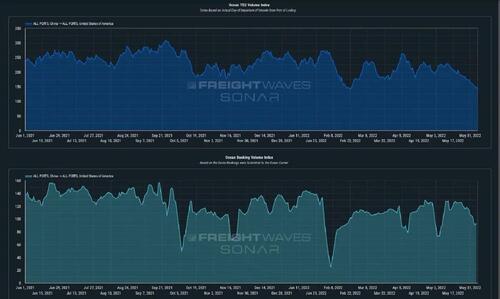

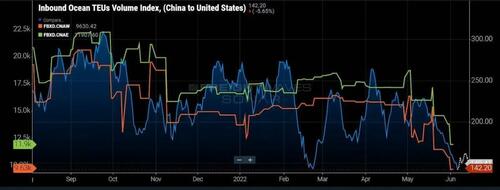

The latest ocean container bookings data reveals that despite the strong levels of inbound cargo during the first five months of 2022, import demand is not just softening — it’s dropping off a cliff. Because capacity on the trans-Pacific has remained relatively stable, Drewry’s container spot rates from China to the West Coast have plunged 41% month-over-month to $9,630.

Freight forwarders will enjoy expanding margins on ocean freight, while U.S. trucking carriers and intermodal volume providers may start to see volume risks.

Consumer buying patterns are rapidly normalizing to pre-COVID levels, and U.S. retailers are stuck with too much inventory. Target shares dropped Tuesday morning after executives said the company would mark down unwanted items, cancel purchase orders and move quickly to get rid of excess inventory.

Container imports bound for the U.S. have dropped over 36% since May 24. (This index measures departing container volumes at the port of origin). This is a troubling sign for domestic U.S. freight markets that have been benefiting from an unprecedented surge of containerized import volumes over the last 18 months. Since ocean transit times for these inbound container volumes have recently been averaging between 30 and 35 days, we will begin seeing the softer volumes show up at U.S. ports in the first couple of weeks of July.

This also puts U.S. containerized imports from all countries of origin down 36% year-over-year, which is a reversion back to the volume levels of the summer of 2020. But what is the cause of the sudden drop in containerized import volumes? Well, there are a few simultaneous factors converging that serve as likely explanations for why volumes are suddenly dropping.

The inventory glut

At the forefront of these reasons is the buildup of inventory here in the U.S. resulting from companies attempting to both replenish inventories that were largely depleted in 2021, but also from these companies wanting to keep enough inventory on hand in case of any further disruptions that may occur. Consecutive rounds of COVID lockdowns in China only exacerbated those fears, but after the war between Russia and Ukraine broke out more than 100 days ago, the geopolitical risks seem to only be escalating, and for better or for worse, companies decided that they would rather have the inventory safely here in the U.S. than risk having it abroad should there be a sudden surge in consumer demand.

So, if consumers are now shifting buying trends from goods to services, those goods-producing companies may get stuck with too much inventory or the wrong inventory in order to try to capture sales. This buildup of inventory will inevitably lead to a slowdown in new import orders abroad and thus will only add to the demand destruction we are seeing for containerized imports into the U.S. Just Tuesday Target announced an “aggressive” inventory reduction plan led by canceling orders and marking down even more inventory.

The chart above, displaying rising inventories, and the chart below, displaying falling imports, reveal that retailers are upside down after the last surge of freight to hit the United States’ shores and are throttling down freight velocity in their networks.

The consumer is getting crushed

Conditions for the consumer seem to be getting worse and worse as inflation takes hold and prices get more and more expensive. Just this week, AAA reported a new record high for gasoline prices at $4.51 per gallon on its national index.

Some economists speculate that with the Fed beginning to raise rates and draw down its balance sheet, we may be experiencing “peak inflation.” However, even if inflationary pressures begin to ease, consumers may still be overexposed to rising interest rates through the use of credit in a way that could further deteriorate demand and discretionary spending.

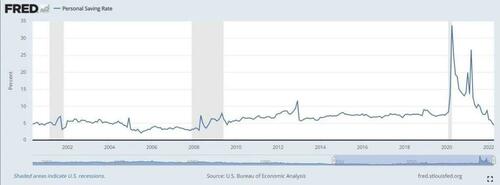

Credit card spending has been accelerating at a time when personal savings rates have continued to decrease and move toward some of their lowest rates (last reading 4.4) since the Great Financial Crisis (4.5 in August 2009). There are two ways to read very low savings rates: either consumers are exceptionally confident and exuberantly spending their money or consumers are spending every last dollar they have in an attempt to keep their heads above water in a high-inflation environment. Either way, there isn’t any slack left in consumer wallets — it’s hard to imagine consumer spending growing from here.

Unfortunately, inflationary pressures in energy and food don’t know or care that American consumers are out of money — inflation in those sectors was caused by supply shocks, not artificially stimulated demand. It is also important to keep in mind that the rate of growth for the Producer Price Index has been outpacing the Consumer Price Index, so some producers may still be taking some hits from rising costs that have not yet been passed on to the consumer.

So even though total revolving credit outstanding is just at pre-pandemic levels, it is nonetheless accelerating, and if prices continue to rise, it is reasonable to expect that revolving credit outstanding will rise as well.

At first glance, one may look at retail sales (charted below) and conclude that they are growing, but keep in mind that the report is measured in nominal dollars unadjusted for inflation and represents increases in the prices of goods being sold — not so much the strength or resilience of consumers. Goods-producing companies will not be alone. Services and tech companies will also be under pressure in the coming months, and sell-offs could lead to layoffs.

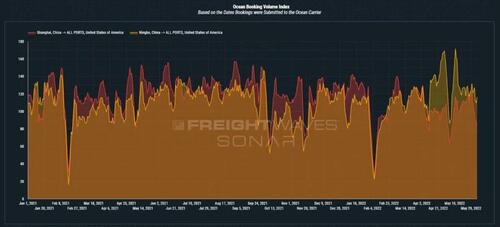

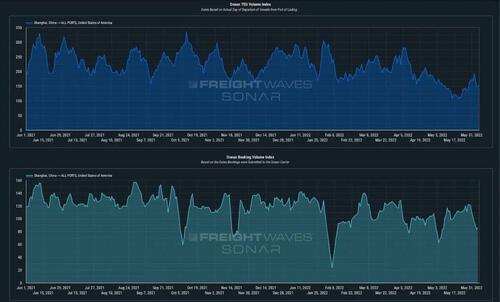

As we see a growing number of signs pointing toward further demand destruction from U.S. consumers, and thus a further reversion of import container volumes back to levels closer to 2019, it is worth examining the trade lane that handles a majority of that volume: China to the U.S.

When looking at aggregated volumes from China to all U.S. ports, we are able to see that volumes have been declining from the “peak of peak season” in September 2021 through Tuesday (currently down 51% from that peak). While late March through the beginning of May is historically (pre-trade war/pre-pandemic) a softer period for volumes on this trade lane, it is important to realize that this decline in volumes has also been amplified by the COVID restrictions and lockdowns implemented by the Chinese government in Shanghai as well as other important manufacturing regions in China (most notably around Beijing and its major nearby port of Tianjin).

Despite the lockdowns, a decline in volumes on this major trade lane was seemingly inevitable in 2022 as the massive volumes moved between these two countries in 2021 were at unprecedented and unsustainable levels. Now some industry observers are calling for a “container surge” as China reopens, but it seems that the demand destruction has already spilled over into this trade lane in a big way.

The ‘container surge’ that never was

The “container surge” that many have been expecting from Shanghai (thought to be building during the lockdowns) appears to have mostly already been rerouted through the Port of Ningbo (yellow). With access to the Port of Shanghai being largely blocked due to landside restrictions (i.e., road closures), shippers were quick to reroute volumes through the closest alternate major port to the Port of Shanghai (red). Since the lockdowns began in Shanghai in late March, the decline in Shanghai new bookings (and thus load volumes) has been more than offset by a surge of volumes through Ningbo from rerouted containers. This led to booking lead times hitting their lowest levels on record as shippers scrambled to get their volumes moving.

Despite the reopening of Shanghai, total container volumes from China to the U.S. have continued their downward trajectory, and that trend is not likely to be reversed by an easing of COVID restrictions alone. As of the latest data points, if this is the “container surge” from Shanghai to U.S. ports upon its reopening last Wednesday, then right now, it is barely a “blip on the radar” compared to the volumes from Shanghai to the U.S. that what we have seen over the last 18 to 22 months. This could easily change within our bookings data for the weeks ahead, and if there is pent-up demand, it will undoubtedly show up in the bookings data, but as of Tuesday, it has not yet materialized in any significant way.

This steady decline in volumes from China to the U.S. has also put significant downward pressure on spot rates from the demand side. As capacity remained relatively consistent in the first few weeks post-lockdown (March 28 onward), the drop in volumes caused a decline in both the Freightos Baltic Daily Index and the Drewry World Container Index spot rates from China/East Asia to the U.S. West Coast (down 41% per FEU month-over-month [m/m] – $9,630), as well as from China/East Asia to the U.S. East Coast (down 36% per FEU m/m – $11,907). While this has been a welcome downturn in spot rates for shippers that battled the record-setting spot rates of 2021, we should also keep in mind that these spot rates remain elevated on a y/y basis (73% to the West Coast and 59% to the East Coast).

If bookings continue to soften through June, we expect to see spot rates on this trade lane decline further, but ocean carriers may go to greater lengths than ever before to try and protect their record-setting earnings. They have already been cutting capacity on major trade routes through measures such as blank sailings and reassigning vessels to other services, but if the decline in volumes accelerates in the weeks ahead, we may see the alliances test their strength and discipline like never before.

If rates start dropping quickly, it is reasonable to suspect that the ocean carriers that have not locked in a majority of their allocations in longer-term contracts may begin aggressively undercutting one another as they compete in the spot market.

Interestingly enough, the last port labor negotiations at LAX/LGB that caused disruptions to supply chains (and thus led to a buildup of inventory in the U.S.) in 2014-15 created a similar situation. Coming off of a record year, that may sound like an unlikely scenario, but there is a distinct possibility that sharply softening spot rates could cause a shakeup and/or reorganization of the current alliances.

https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/us-import-demand-dropping-cliff